Biodynamic: A different kind of farming

Published 2:14 am Thursday, August 17, 2017

- Biodynamic: A different kind of farming

Biodynamic agriculture involves unusual practices, but producers stand by their results

By John O’Connell

Capital Press

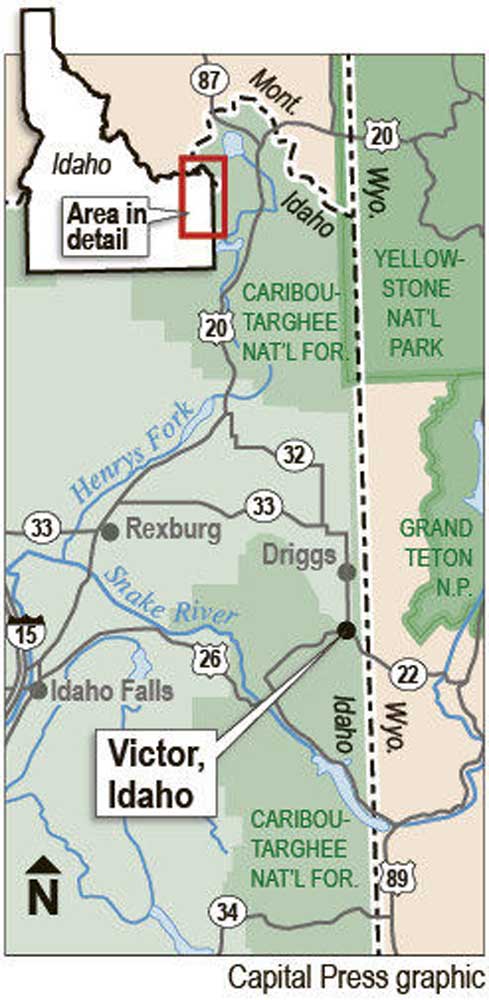

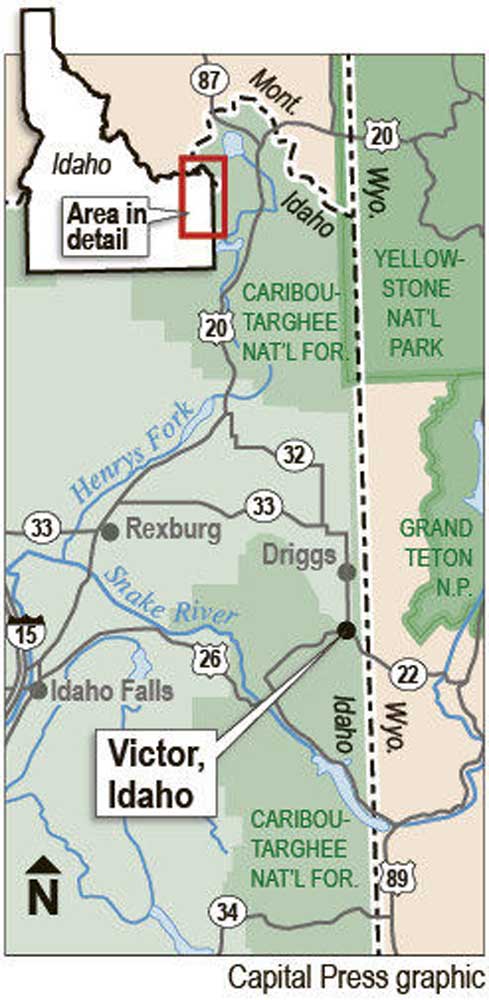

VICTOR, Idaho — “Auntie Em!”

A small, Brown Swiss cow grazing in sight of the Teton Range raised her head upon hearing Mike Reid’s call. She trotted to her master’s side and licked his face.

“My cows are pets,” explained Reid, owner of Paradise Springs Farm, a 30-cow dairy where the livestock have names and are celebrated for their unique personalities. “Some people have cats and dogs; I have cows.”

Paradise Springs is part of a cluster of small farms employing biodynamic agricultural practices in this small, Eastern Idaho town. The quirky, management-intensive system arrived in the U.S. in the early 1990s. In recent years, domestic biodynamic production, though still tiny compared to conventional farming, has grown by 10 to 15 percent a year. But it’s long been popular in Europe and traces back to the 1920s, when German philosopher-scientist Rudolf Steiner gave lectures on an approach to food production that regarded a farm as a self-sufficient “organism,” shunning chemical fertilizers and farm inputs and promoting a variety of esoteric production practices designed to help crops and livestock better capture “cosmic” energy.

“It is a method of organic agriculture that predates the national organic program by 70 years,” said Jim Fullmer, executive director of Junction City, Ore.-based Demeter USA, the nation’s biodynamic certification authority. “This is like the grandmother of all of it.”

Fullmer said public awareness of the system has surged in the U.S. during the past decade, based on its growing popularity among West Coast wineries seeking to differentiate their products — and claim massive price premiums.

Fullmer and the Victor producers believe the nation is on the cusp of yet another “foundational” biodynamic trend.

Demeter has been flooded in recent months with calls from marijuana growers. Though recreational pot use has been legalized in many states, including Oregon and Washington, it’s still not legal federally, leaving growers without the option of seeking federal organic certification. Medical pot use is allowed in California, which is scheduled to legalize pot for recreational purposes starting next year.

Biodynamic farming is a closed-loop system, with animals at its heart. The animals provide compost for crops and are in turn supported by farm-raised forage.

By promoting diverse insect and soil microbial life, biodynamic farmers keep pests and diseases in balance without chemicals, explained Ken Michael, who runs Victor-based Teton Full Circle Farm with his wife, Erika Eschholz.

“It’s pretty much self-sustaining,” Michael said. “Water and sunlight are the main inputs.”

Certified growers must meet the baseline requirements of organic farming. In addition, they must spend at least a year demonstrating their mastery of nine required homeopathic treatments, which are many times ridiculed by those in mainstream agriculture.

One treatment, for example, entails burying manure in a cow horn, thereby “amplifying” natural energy to accelerate its conversion to humus, which is used to inoculate compost with beneficial microbes. Another treatment involves burying a horn with pulverized quartz, which is added in small doses to water and sprayed on foliage to stimulate photosynthesis.

Some producers, such as Michael, base crop decisions on a celestial planting calendar, which he explained “follows the moon through the various constellations” and “makes sure we’re in the rhythm that the plants are following.”

The Victor farmers explain the homeopathic treatments are complex and aren’t fully understood by science, making them difficult to explain to the public. They contend farmers must experience the benefits of the treatments to believe them. Clusters of biodynamic farms often develop as workers versed in the system leave to start their own operations nearby.

Demeter USA had certified 15 farms in 1993. Today, 300 farms are certified biodynamic. Biodynamic farmers pay Demeter a $420 annual renewal fee, plus half a cent for every dollar in earnings, and are subjected to an annual audit.

Reid speaks of his favorite cow, Glenda Goodwitch, to prove his system’s effectiveness.

Goodwitch, mother to Auntie Em, is 14 years old and remains the top milk producer on his dairy. The geriatric cow is pregnant with another calf.

Reid, who holds the first raw milk permit issued in Idaho, was recently recognized as having one of the 10 best organic dairies in the U.S. by the Cornucopia Institute, a nonprofit organization that promotes organic agriculture.

“If you treat your cows as well as you treat your pet dog, they’ll return just as much love, and even better, a lot of good milk,” said Reid, who has trained his cows not to defecate inside the barn.

Reid acknowledges his yields can’t compare with conventional dairies, but his customers pay a considerable premium for milk they believe delivers better nutrition and “energy.” Local families who subscribe to his delivery service pay $12 to $15 per gallon for his raw milk, and up to $35 per pound for his raw cheese.

The Teton Valley’s first biodynamic farm, Cosmic Apple Gardens, opened in 1996. Founder Jed Restuccia and his wife, Dale Sharkey, raise vegetables, beef, poultry and eggs on their 50-acre farm, selling food directly to customers through a community supported agriculture arrangement. Cosmic Apple animal products, however, are labeled only as organic, since the farm imports too much outside feed for them to meet biodynamic specifications.

“It’s healing the Earth through agriculture, and that’s what we want to do,” Sharkey said.

Full Circle Farm sprang out of Cosmic Apple, where Eschholz worked for 11 years, starting as a volunteer. Full Circle employs one worker and two interns and offers 20 CSA “work shares” for supplemental labor. People who put in several hours per week of weeding, harvesting and other chores get free produce.

Most vineyards seek to plant “every square inch” of their property in grape vines, explained Jeffrey Landolt, vineyard and estate director at Benziger Family Winery in Glen Ellen, Calif.

About 20 years ago, however, Benziger commenced with tearing out vines, as it started on the path toward becoming biodynamic.

In addition to grapes, the 90-acre farm is now also home to about 1,000 olive trees, a fruit orchard and flower gardens, which promote a diversity of insects to keep harmful pests in check. Bird boxes are scattered throughout the property — habitat for blue birds that also play a role in insect control.

And though the industry has long valued bare soil to avoid competition with vines, Benziger plants specialized blends of cover crops — plant species raised primarily to benefit soil health — beneath the grapes. Benziger maintains a flock of 80 sheep to graze the cover crops and add manure to the system. Bedding, manure and spent grape skins are also composted together for additional fertility.

The percentage of organic matter in the farm’s soil has grown from 1 to 3 percent under the biodynamic system. Landolt explained that Benziger is “pushing the envelope” of biodynamics, having developed some of its own homeopathic treatments. For example, the farm has experimented with different minerals to use in the preparation intended to stimulate photosynthesis.

Benziger’s biodynamic wines sell for $60 to $100 per bottle, containing a “unique and a wider swath of the potential flavor and aroma profile.”

“I think we’re about to explode in biodynamic agriculture (production) in general,” Landolt said.

Fullmer, the biodynamic certifier, said 70 vineyards, mostly on the West Coast, are currently certified biodynamic.

“What initially brought biodynamics to the U.S. consumer’s mind was wine,” Fullmer said. “Wine is a great ambassador.”

In the near future, Fullmer anticipates many marijuana growers who call themselves “farmers” will have to earn the title — at least if they hope to receive his association’s certification.

Biodynamic pot growers are expected to raise livestock to generate compost for their high-value crops. They’ll also have to implement diverse crop rotations. But the payoff is considerable for those willing to make the investment. One grower reported selling biodynamic pot for $60 per eighth-ounce, compared to about $35 for a standard variety raised under natural light.

“They’ve been lab technicians up until now, but cannabis producers are becoming farmers, which is a beautiful thing,” Fullmer said.

Under Oregon’s industrial hemp license, Fullmer raises a medicinal cannabis variety with several “healing compounds” but without the psychoactive ingredient, THC. His own crop rotation includes medicinal herbs, such as yarrow and red clover blossom. He also has a herd of Scottish Highland cows.

Fullmer has fielded calls from processors throughout the country seeking a certified biodynamic marijuana supply for oil extract production. Only eight growers are now certified or in the process of becoming certified.

Alicia Rose, founder of HerbaBuena in Northern California, makes medicinal marijuana extracts and topical products. She was the first to inquire with Demeter about certification for marijuana. Familiar with biodynamics as a consultant to high-end wineries, Rose figured the system represented a good alternative to pot farmers who are excluded from seeking federal organic status.

Rose helped a Sonoma fruit and olive farmer become the first Demeter-certified pot grower and now has six biodynamic suppliers.

“A lot of people buy it only because it has the word ‘certified’ on there,” Rose said. “In some ways, we’re lucky we live in Northern California and there’s been a considerable biodynamic movement here, especially because of the wine growers.”

Rupert, Idaho, crop scientist Jeff Miller recalled a period about 15 years when compost teas enjoyed short-lived popularity among many local potato farmers.

In his own trials, Miller noticed no benefit from the teas — compost concentrates mixed with water and applied to soil to boost beneficial organisms.

However, a grower who attended his field day swore she had success with them. A year later, the grower acknowledged she’d switched back to conventional methods, and that her promising results were likely based on her own desire for compost teas to work.

Miller sees parallels between that grower and those who report successes with some of the more unusual biodynamic practices.

“Let’s say I do five things to my crop and three work and two don’t,” Miller said. “Without properly controlled scientific studies, it’s hard to know what things are giving you the benefit.”

Washington State University soil science professor John Reganold is among a small group of researchers who have studied biodynamic farming in depth.

Colleagues have suggested that Reganold is “out of his mind” to give the system any consideration, he said.

“I say, ‘No, they’re farmers, and they’re good farmers. They’ve got good soil, and they’re making money,” Reganold said.

Reganold emphasizes the system generally preaches sound farming fundamentals, such as good care for animals, crop diversity, building soil health and sustainability. Reganold’s research has confirmed a slight increase in compost temperature, as well as improved respiration of soil organisms, following the addition of manure from a buried cow horn.

He’s seen no evidence to support claims that any of the homeopathic preparations directly result in production gains. Indirectly, however, he’s certain biodynamic farmers benefit from the preparations because they’re forced to spend more time observing their fields.

“Organic is getting bigger and bigger, and now people are saying, ‘We want a different edge,’” Reganold said.