Grazing accused of worsening climate change impacts on Oregon spotted frogs

Published 4:30 pm Tuesday, May 24, 2022

- Fremont-Winema grazing

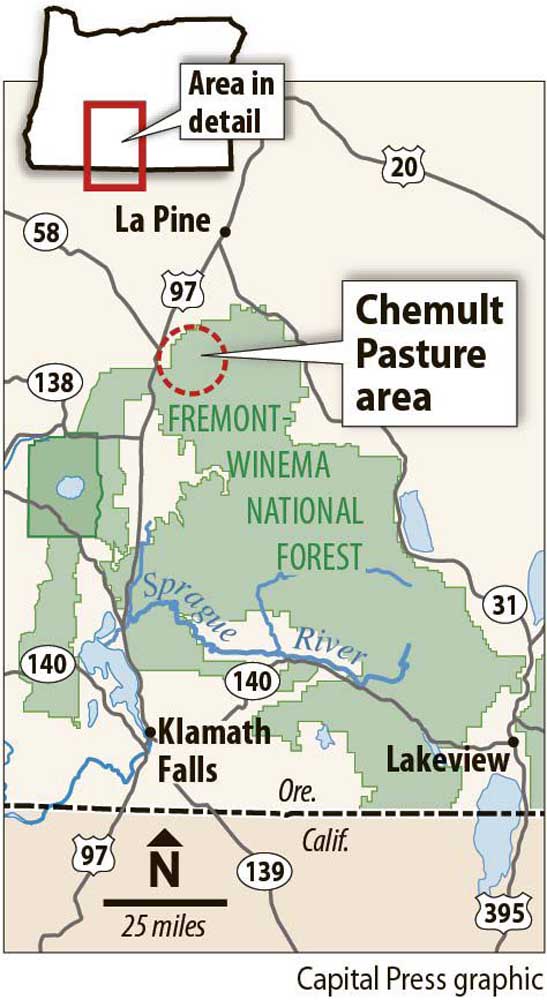

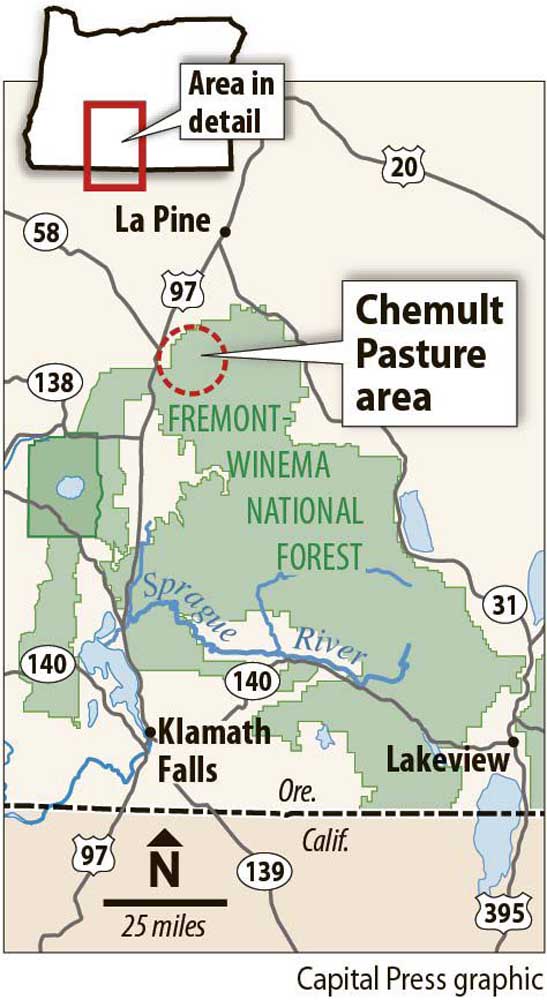

EUGENE, Ore. — A grazing plan is under attack for allegedly failing to adequately examine climate change effects on Oregon spotted frogs in the Fremont-Winema National Forest.

In a lawsuit, environmental advocates claim that federal officials didn’t sufficiently analyze how more frequent and severe droughts will aggravate impacts from grazing on the protected species.

“You can’t assume the same hydrologic conditions that occurred the last 10 years will occur the next 10 years,” said Lauren Rule, an attorney representing the Concerned Friends of the Winema and four other environmental nonprofits.

While climate change was mentioned in an environmental review of the grazing plan, the groups claim it didn’t account for water conditions growing worse over time.

“It did not consider all the factors that it needed to consider,” Rule said during May 24 oral arguments in Eugene, Ore.

The environmental plaintiffs filed a lawsuit against a grazing authorization for the 160,000-acre Antelope Allotment in 2019, arguing the permit violates the national forest plan, the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act.

The nonprofits have now asked a federal judge to declare the U.S. Forest Service’s “allotment management plan” to be unlawful. They also want the judge to shut down grazing in two pastures, Chemult and North Sheep, that make up roughly half the allotment.

U.S. District Judge Michael McShane asked the environmental plaintiffs and federal officials to focus on climate change effects during oral arguments held May 24 in Eugene, Ore.

Droughts reduce water levels in Jack Creek, which flows through the allotment, as well as the number pools that attract both frogs and cattle, Rule said. “If much or most of the creek is limited to intermittent pools, that’s when we have the problem.”

Cattle drink from these remaining pools, decreasing water supplies and polluting them with manure while trampling or displacing frogs, according to the plaintiffs.

Tadpoles are vulnerable when the waterway dries up earlier than normal, if they’re not yet mature enough to hop toward moisture, Rule said. “If they have not metamorphosized to find pools in the creek, they will die.”

The Forest Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service did not recognize that such problems will become worse while examining strategies to mitigate grazing impacts, the plaintiffs said.

Their mitigation measures aren’t specific or timely enough to protect the frogs when they’re facing multiple stresses from drought, Rule said.

For example, the rules don’t set clear directives for when or how quickly cattle must be fenced off or removed from pasture, she said. “It all sounds good but it will take time and these frogs don’t have time.”

Sean Martin, the federal government’s attorney, countered that the environmental review complied with all the relevant laws and relied on the best available science.

Federal officials recognized that recurrent droughts harm the frogs by drying up water sources, so the plan requires ranchers to exclude cattle from Jack Creek when stream levels are low, he said.

“I don’t think it pulled any punches,” Martin said.

A “biological opinion” required under the Endangered Species Act included mandatory protections that are meant to prevent injury to the frogs during drought conditions, according to the government.

“It has consequences if it’s blown off, judge,” he said. “If the permittee did not abide by the ESA, they’d be looking at major problems in the future.”

The law doesn’t require “perfection” from the federal government’s analysis, but it does require a “rational framework,” Martin said. In this case, the conclusions and protective measures implemented by federal scientists are entitled to deference.

“Their job is policing the ESA,” he said. “I don’t think we want to assume the biologists and rangeland ecologists acted negligently or in bad faith.”

When the government’s review was completed in 2018, the full extent of climate change impacts on the species wasn’t known, according to the government. Including rising global temperatures in the analysis would have been speculative.

Even so, climate change was considered in depth when the federal government decided to list the species as threatened, the government said.

More is known about the impacts from climate change on salmonids, but those are different species that have been more extensively researched than the Oregon spotted frog, Martin said.

“Here, judge, I don’t think we have that link. We did not want to guess one way or another,” he said. “The consultation is on the grazing rather than climate change standing alone.”