Northwest vs. Southeast: Timber industry grows where it thrives

Published 7:00 am Thursday, May 12, 2022

- Lumber production 050522

ROSEBURG, Ore. — The timber industry may be synonymous with the Northwest in the popular imagination, but the economic reality is the industry’s center of gravity has quietly shifted to the South.

The region’s wood products manufacturing sector has been losing market share to the U.S. Southeast for years and it’s not expected to recover its momentum in the foreseeable future.

Its thunder has been stolen by the South’s abundant timber supplies and looser environmental regulations, which have fueled a boom in new production facilities.

Those mills can buy logs at lower prices while supplying lumber for housing construction that’s surging right in their backyard.

“If you know the demand is in the Southeast and the supply is in the Southeast, it’s logical that’s where you’d build your capacity,” said Eric Geyer, strategic business development director for Roseburg Forest Products. “Without any more fiber supply, the Northwest’s growth is stagnant or declining slightly. It will mirror the available fiber.”

Roseburg Forest Products was founded in Oregon more than 85 years ago but five of its 13 mills are now in the Southeast, where it began investing about 15 years ago.

The company bought most of those facilities, as well as 200,000 acres of forestland, in just the past five years.

“There’s a value in diversification, both in products and in geography,” Geyer said. “Our customers are nationwide, so our facilities should be in all those locations.”

The South has increased its lumber milling capacity by about 30% in five years, or about 5.5 billion board-feet, mostly by building new facilities but also by renovating older ones, according to the Beck Group, a timber industry consulting firm.

Lumber production in the Western U.S. still slightly outpaced the South in the early 2000s despite protections for threatened species that restricted logging on federal lands.

However, the region lost its lead during the collapse of the housing market after the 2008 financial crisis. Since then, the production gap has only widened.

South keeps growing

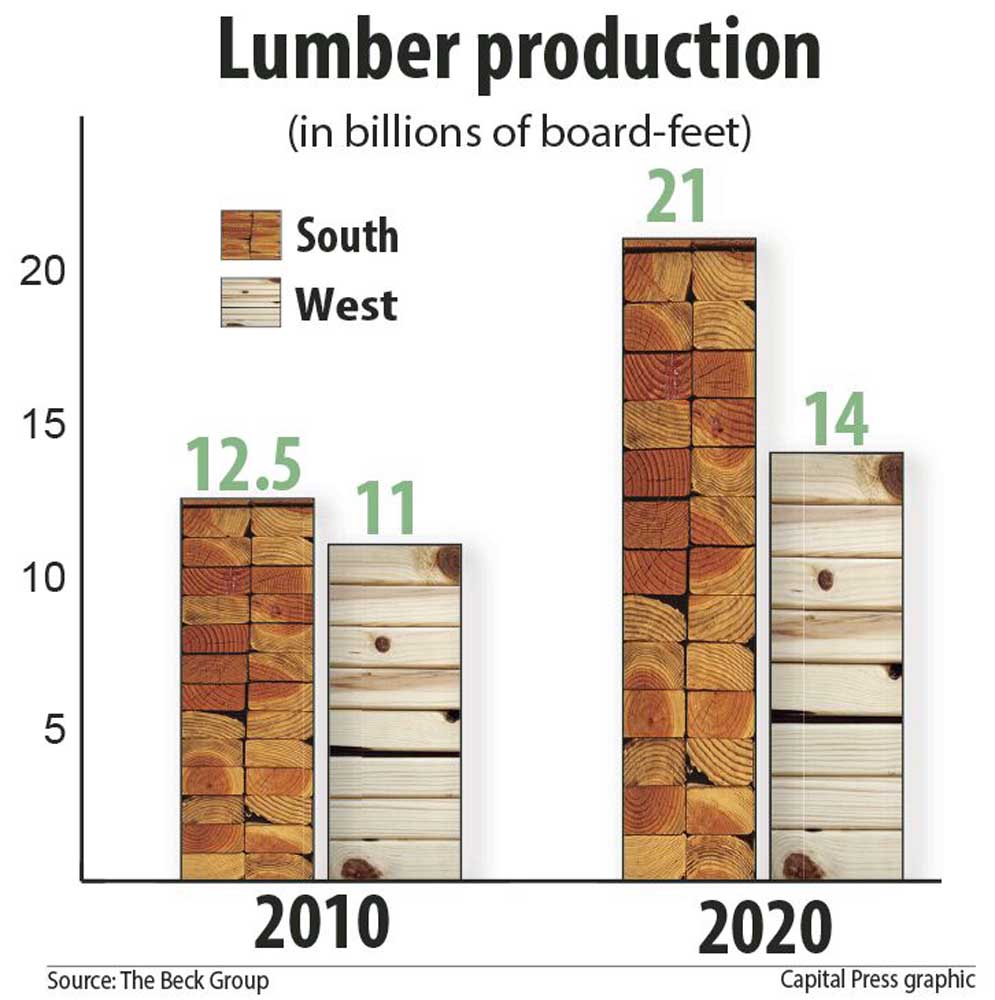

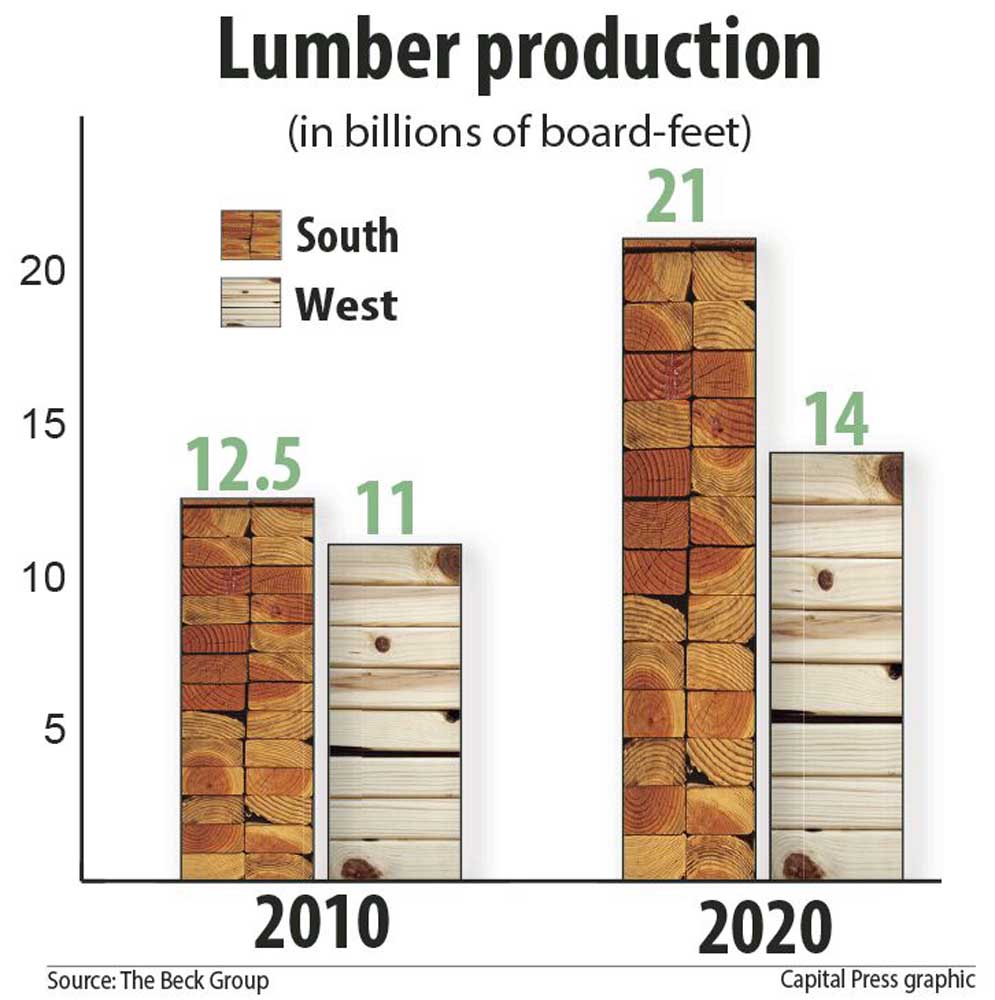

The South produced about 21 billion board-feet in 2020, up from about 12.5 billion board-feet a decade earlier.

To compare, the West’s output rose from about 11 billion to 14 billion board-feet in that same period.

“Billions of dollars are being invested in the South. They don’t have the spotted owl and the marbled murrelet and some of the others that have impacted the lands here,” said Bryan Beck, president of the Beck Group. “The West has been a more challenging place for sawmills for decades now.”

While the South is now the top lumber-producing region in North America, that doesn’t mean the West’s timber industry will “collapse,” he said.

The region’s battle-hardened sawmills remain competitors despite the uneven playing field.

“The silver lining is the folks who are here, who have survived, are very good at what they do,” Beck said. “They have strong manufacturing know-how.”

Southern advantages

The South’s rise in the timber industry isn’t strictly a function of environmental laws reducing harvest levels in the West.

Federal policies have long encouraged Southern farmers to plant trees on marginal agricultural lands, resulting in a surplus of inexpensive pine logs for the region’s sawmills.

Aside from incentives that expanded forestland acreage, the Southern pine is a fast-growing species that’s logged about 25 years after planting, said Tom Schulz, vice president of resources and government affairs for the Idaho Forest Group.

Tree species in the intermountain West, where the company is based, are typically harvested at 75 years of age, he said.

“Over there, you may have three crops in that same period of time,” Schulz said.

Much of the forestland near the company’s six mills in Idaho and Montana is owned by the federal government, which means logging projects entail strict environmental reviews and restrictions.

The forestlands in the South are mostly on private property, which is one reason the Idaho Forest Group is building a mill in Mississippi that’s expected to start operating this year.

“You do have national forests down there but they’re very small contributors to the overall supply,” Schulz said.

Pine beetle problems

As forestland has expanded in the South, another major North American timber region has endured a slow-moving catastrophe that’s forced manufacturing capacity to relocate.

Mountain pine beetles have devastated some British Columbia, Canada, forests, which required large-scale logging of dead and dying trees to ensure the logs retain salvage value.

That supply of damaged timber is now dwindling but replacement trees won’t reach harvestable age for many decades, prompting some Canadian companies to invest in the South.

“With the loss of wood coming from Canada, that gap will be made up for by the South,” said Roger Lord, president of the Mason, Bruce & Girard natural resources consulting firm. “The West doesn’t have the capacity to absorb that volume.”

New opportunity

Meanwhile, the North American wood supply equation continues to change.

Billions of dollars slated for thinning and fuels reduction in national forests were approved under a federal infrastructure bill last year, raising the possibility of more harvests on Western public lands.

To be effective, the federal government should avoid “random acts of restoration” and instead implement a coherent strategy for enhancing forest resilience, said Travis Joseph, president of the American Forest Resource Council, a timber group.

“It can’t just be a one-off treatment,” he said. “Our current system and the forest health and wildfire crisis are not compatible.”

Opposition from environmental groups is bound to be an obstacle, but there is a real opportunity to reduce the congestion that’s resulted from stagnating timber harvests, Joseph said.

“I don’t accept that has to be our status quo,” he said.

Tighter restrictions

While there’s a potential for more logging on federal lands, new harvest restrictions by Northwest state governments are a certainty.

Washington is dedicating forestland to storing carbon, making those areas off-limits to commercial logging. Oregon is contemplating a habitat conservation plan for threatened and endangered species that would also decrease logging on state forests.

Private lands aren’t immune from state logging restrictions, either. Earlier this year, Oregon lawmakers approved a compromise deal between environmental and timber interests to widen no-harvest buffers around streams.

The long-term implications of this “private forest accord” are up for debate in the timber industry.

Among critics of the legislation, it’s bound to harm landowners while causing closures and curtailments at sawmills that can’t get enough logs.

“They’ve had their private property rights taken away and the value of their land is diminished,” said Rob Freres, president of Freres Lumber Co. in Lyons, Ore. “If I was a small woodland owner today, I’d be harvesting to capture the value before it’s taken away from me.”

However, that opinion is not unanimous.

Greenwood Resources, a company that manages forestlands and owns property in the Northwest, believes the bill has stabilized the regulatory outlook for landowners.

“It offers more certainty for our investments,” said Kevin Brown, the company’s Pacific Northwest area manager.

High log costs make it tougher for Northwest sawmills to compete against those near the “wall of wood” in the South, said Chad Washington, the company’s stewardship and community engagement coordinator.

On the other hand, Northwest landowners are in a stronger position because timber isn’t oversupplied, he said.

“Just as an increase in demand drives prices up, so does a decrease in supply,” Washington said.

Constraints on the Northwest wood supply will limit the region’s milling capacity but that doesn’t mean the industry is in decline, he said.

“We’ve hit that equilibrium of outlets to land base,” Washington said. “It’s a good place to be a mill owner but not to invest in a new mill.”

When sawmills compete over a smaller number of logs, that does tend to boost prices in the short term.

However, long-term supply reductions make it harder for mills to stay in business, said Hakan Ekstrom, president of the Wood Resources International forest market analysis firm.

“Every time you have some new regulations that limit supply or make it more expensive to harvest, you’ll likely see some sawmills or plywood mills curtail or shut down permanently.”

If fewer mills are competing for logs, that prevents prices from getting bid up, particularly for sellers with few market options, said Brooks Mendell, CEO of the Forisk forestry research firm.

“Losing mills is bad for landowners,” he said. “Part of the logic of timberland investment is there are multiple independent log buyers out there.”

At current prices, the South is on track to produce $16 billion worth of softwood lumber in 2022, compared to $10-11 billion in the West, Mendell said.

On a national scale, lower raw material costs mean Southern lumber mills can extend their reach into markets traditionally served by Northwest facilities.

“They can produce it for cheaper than what we can produce it for, which gives them the ability to ship it further,” said Doug Cooper, vice president of resources for Hampton Lumber, an Oregon-based manufacturer.

The Northwest’s iconic Douglas firs have long been recognized for producing stronger and straighter boards than Southern pines, which does provide an advantage in the construction industry, he said.

Mill upgrades

Sawmills in the Northwest are investing in new equipment that saves on labor and maximizes the value of each log, but the South is also upgrading its milling technology, said Steve Zika, Hampton Lumber’s CEO.

For example, continuous drying kilns are preventing the warping that historically impeded the desirability of Southern pine lumber, he said. “By drying the lumber better, you get a better quality piece out of it.”

The Northwest’s restricted wood supply means sawmills “will be put to the test again to remain viable,” but the region’s timber industry doesn’t face an existential threat, said Geyer of Roseburg Forest Products.

Ultimately, the shift in investment toward the South doesn’t represent a defeat for the Northwest so much as a strengthening and diversification of the national industry, Geyer said.

The real competition is between U.S. lumber products and imports from China, Russia, Chile and Brazil, he said. “They have nothing close to the environmental restrictions or the science-based management we have here in the United States.”