ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 2:13 am Thursday, May 3, 2018

SHOSHONE, Idaho — This year’s combination of bountiful reservoirs and slow-melting mountain snowpacks have been a blessing to the Idaho Water Resource Board as it returned a record amount of valuable water to the ground, recharging the enormous Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer that quenches a large portion of the state’s farms and ranches.

Agriculture is Idaho’s economic engine, generating nearly $28 billion in total sales each year and more than 128,000 jobs. Nearly half of the state’s $7.2 million in crop and livestock production comes from the Snake River Basin, where most of the state’s 2.8 million irrigated acres are fed by the Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer, one of the largest and most productive aquifers in the world. At about 10,800 square miles, it is larger than the surface of Lake Erie.

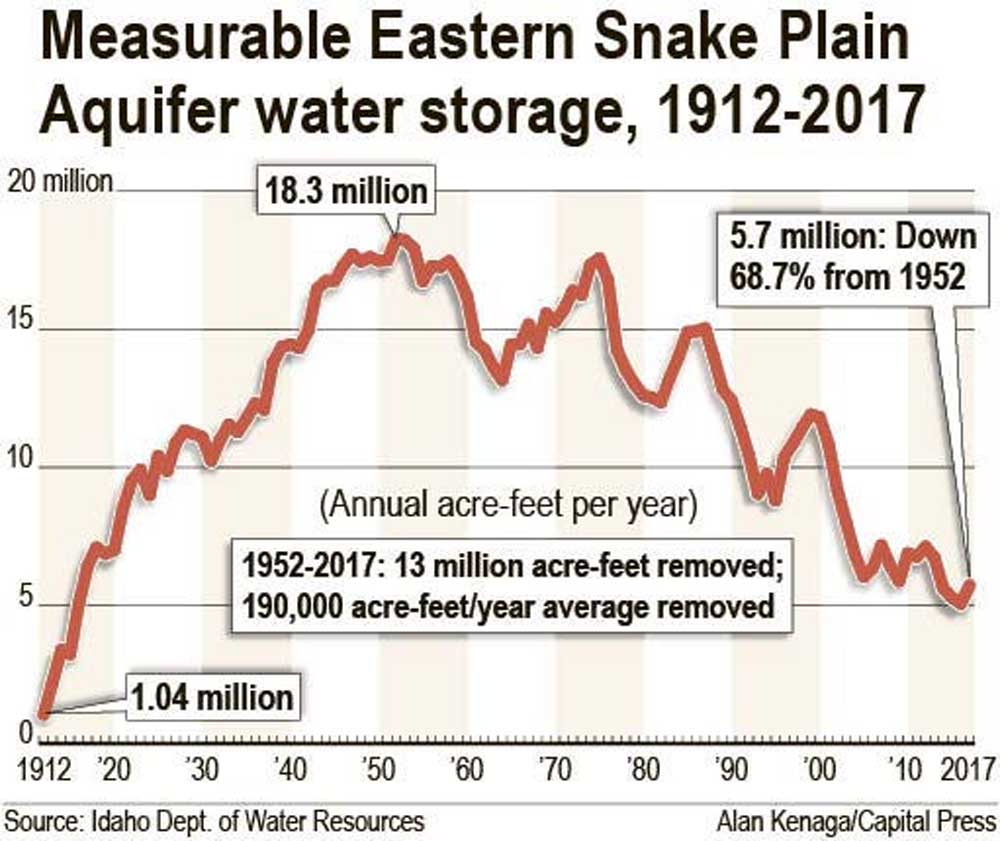

But farmers and water managers have faced a reckoning in recent decades as the aquifer’s levels began to sink under the stress of higher water use and more efficient irrigation systems that didn’t allow water to percolate back into the ground. Since 1952, the volume of available water had dropped nearly 13 million acre-feet.

“We had to do something; we couldn’t just watch the aquifer be depleted,” Vince Alberdi, a state water board member and former long-time manager of the Twin Falls Canal Company, said.

The board molded the state’s 2009 Comprehensive Aquifer Management Plan that took on the goal of restoring and sustaining the ESPA. The plan addressed what had to be done to arrest the depletion and to manage all available water and use it efficiently, he said.

This year’s recharge efforts are expected to pay off handsomely, with 530,000 acre-feet — enough to cover 400,908 football fields with a foot of water — seeping into the underground reservoir.

This year’s bounty more than doubles the board’s goal of recharging 250,000 acre-feet annually, averaging wet years with dry ones — and far surpasses last year’s record of 317,000 acre-feet.

In its goal to replenish the ailing aquifer, the board has been impressively forward-thinking, Wesley Hipke, IWRB recharge project manager, said. The plan also included conversions from groundwater use to surface water use, water conservation, cloud-seeding and measuring water use.

“You can’t manage it unless you measure it,” Alberdi said.

Measuring water use made people more conscious of what they were using and more efficient in that use, Hipke said.

“The one thing I think the board has done really well is (looking at) how best do we manage this aquifer, not just recharge,” he said.

Hydrologists don’t know the total volume of water in the Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer, or its capacity.

“We don’t know how deep it is or how much water the basalt rock (below 200 feet) can hold,” Mike McVay, a water resources engineer with the Idaho Department of Water Resources, said.

Hydrologists with the U.S. Geological Survey began monitoring the aquifer in the early 1900s and estimated that it rose about 1 million acre-feet between 1911 and 1912.

Production agriculture — and its accompanying inefficient irrigation practices — would cause it to swell over the next 40 years. Flood irrigation and leaky canals sent water seeping back into the aquifer and by 1952, that incidental recharge had increased the aquifer by more than 18 million acre-feet and increased the flow of the springs it feeds.

Water rights were applied for and administered in those times of higher aquifer and spring levels — and agriculture, its allied industries and the state’s economy grew.

But more efficient sprinkler irrigation and new policies ending winter water diversions and mandating winter storage in reservoir systems have reduced the volume of water going into the aquifer.

Combined with the overallocation of water and increased groundwater pumping, the aquifer went into decline, with an average annual loss of 200,000 acre-feet between 1952 and 2017 — and down to a level not seen since 1916.

There was no turning back from irrigation. The Snake River Plain only gets about 10 inches of precipitation annually, and irrigation water made the desert bloom. Without it, farmers wouldn’t be able to raise potatoes, sugar beets, beans or alfalfa — all major crops in the region, Lynn Tominaga, executive director of Idaho Ground Water Association, said.

“It would be basically a desert,” he said.

Without irrigation, the land would only support dryland grazing and dryland grain production. The region’s dryland winter wheat production only yields 15 to 20 bushels and acre, compared with irrigated production yields of 110 to 120 bushels, he said.

“There’s a big difference in yield, quality and protein,” he said.

Water curtailment would hit the dairy industry particularly hard, losing affordable feed sources to support milk production, which would extend into the processing sector. It would also impact land values, dropping irrigated land values from $3,000 to $7,000 an acre to $100 to $150 an acre, he said.

All told, the economic damage would be enormous, he said.

With so much riding on a healthy aquifer, the state is now trying to balance the budget of water going in and water coming out of the aquifer.

By 2026, the goal is to bring the aquifer up to and sustain it at its average level between 1991 and 2001 — an increase of about 3 million acre-feet above its current level.

“It’s going to take a combined effort to stabilize the aquifer and potentially build it back up,” Hipke said.

That effort will benefit from the historic 2015 agreement between the Idaho Ground Water Appropriators and the Surface Water Coalition in which groundwater users committed to reducing their consumption by 240,000 acre-feet a year.

While the agreement was rooted in mitigating injury to senior water users and preventing curtailments that could have impacted 200,000 acres, it was also key to resolving long-running water-supply conflicts and keeping water management out of the courts.

It also plays a large role in helping to stabilize the aquifer, Hipke said.

Not only are groundwater pumpers reducing what they take from the aquifer, they can offset their annual use by recharging the aquifer, he said.

“There are a lot of moving parts when you’re looking at repairing an aquifer this big. One method is not going to provide the solution,” he said.

The agreement also required groundwater pumpers to install flow meters, with the Idaho Department of Water Resources requiring meters throughout the ESPA in 2016.

The order applies to about 5,400 wells, the majority of which are for irrigation. But it also applies to dairies, municipalities, manufacturing plants and others.

“When you’re taking on a problem this big, you need the data to verify what’s working and what isn’t,” he said.

Despite a couple of minor upticks, the aquifer has been on a fairly steady decline since the 1990s, he said.

Abundant water supply in the 2016-2017 recharge season provided the first notable uptick. In addition to what the recharge plan added to the aquifer, natural recharge brought the total to 660,000 acre-feet year over year in March 2017. The gain was likely even higher, however, because recharge continued until the first of July and natural recharge was more abundant, he said.

State hydrologists are crunching the numbers now to compute this spring’s aquifer level.

“The whole process we’re in is a cultural thing,” Alberdi said.

That process started with a denial there was a water shortage and moved on to proving it. It took years for everyone to come around to understanding how the aquifer works and the need to manage it, he said.

“Change doesn’t happen overnight with something this big,” he said.

It had to be “cussed and discussed” over time to get to a consensus of what has to be done, he said.

Previously, recharge had been done in bits and pieces. The effort started coming together after the aquifer management plan came into play, and it took a few years for the money to catch up with the plan, Hipke said.

Legislative support and state funding to develop recharge sites, maintain infrastructure and pay conveyance fees — the cost of moving the water to a recharge site — have been critical, as have partnerships with canal companies to deliver recharge water, Alberdi said.

“If we didn’t have the buy-in and partnership of the canal companies, it wouldn’t be a viable program,” he said.

“The canal companies already have the infrastructure in place,” Hipke said. “That’s a huge savings.”

Instead of building new infrastructure, the board can spend money on developing recharge sites and paying various groups to deliver recharge water, he said.

That efficiency is keeping the total cost of recharge at about $11 an acre-foot. Other states are having to build new infrastructure for recharge, and that’s costly, he said.

The median cost for recharge in California is $410 per acre-foot and ranges from a low of $80 to a high of $960, according to researchers at Stanford University’s Woods Institute for the Environment.

That wouldn’t be sustainable in Idaho, Alberdi said.

In Arizona, Hipke estimates the cost at $40 to $60 an acre-foot before conveyance fees.

In those regions, canal systems might not be available for recharge because crops are grown year-round. In Idaho, recharge can happen year-round — even during irrigation season if the water isn’t needed, Alberdi said.

Idaho’s cost for recharge includes infrastructure costs amortized over 20 years and average conveyance costs. The cost will increase somewhat in the future, as the program started with the easiest sites to develop. But once the planned capacity is developed, the cost will go down, Hipke said.

While the last two wet years have provided record recharge, more capacity is needed to make up for the dry years, he said.

To date, the board has spent $14 million on infrastructure improvement. By 2024, it is estimated that more than $40 million will have been invested to improve managed recharge capacity throughout the ESPA.

From 2013 to 2017, the board spent more than $3 million in conveyance costs. This year’s record recharge is predicted to cost more than $4 million in conveyance fees.

The board’s current annual budget is $9 million to $10 million — with $5 million from the state’s general fund and the rest from the state cigarette tax.

Idaho’s program is just getting started, with a pilot program begun in the 2013-2014 recharge season. And it’s quite different than what’s happening in other states, where recharge is segmented and site-specific, Hipke said.

It’s reducing the impact throughout the ESPA and spreading recharge across the entire ESPA, he said.

“Idaho has the first state-funded program to this degree. It’s the first state I know of that really takes on a program this big,” he said.

Unlike Idaho, recharge in other western states is done by private and public entities, such as recharge districts, cities and counties. The states regulate those entities and some offer state grants to assist, but they don’t have the cohesive program that Idaho has developed.

State water departments in several western states contacted could not provide Capital Press with the total amount of recharge each year or the costs.

“You look at other states and you see what the results could have been or could be in Idaho,” Hipke said.