ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 2:09 am Thursday, October 25, 2018

When is a potato more than just a potato? When it’s an Idaho potato.

Just ask Frank Muir, president and CEO of the Idaho Potato Commission for the past 15 years. As the commission’s top executive, his job is to convince consumers from Savannah, Ga., to Seattle, Wash., and beyond that the Idaho potato is special.

“Were these potatoes grown in Idaho? That is what we want people to ask,” he said.

Idaho grows excellent potatoes for reasons that include warm days and cool nights; volcanic, mineral-rich soil; and mountain-fed streams that tumble into a sophisticated reservoir system, Muir said. “Our marketing that makes a mystical place of Idaho, across the world, for growing potatoes.”

Many Idaho potatoes also contain a higher percentage of solids, which can be advantageous for processing, he said.

When Muir tells you potatoes are worth getting excited about, it’s based on the 37 years he’s spent helping to turn around some of the country’s best-known brands.

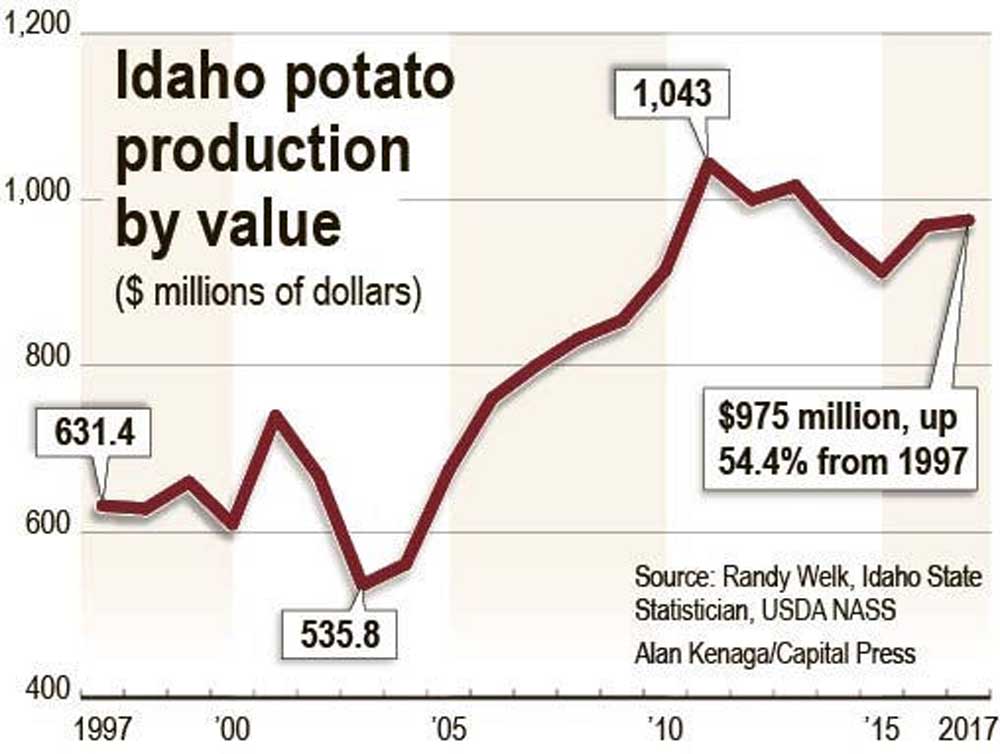

The Idaho potato’s higher profile during the past 15 years has contributed to an 80 percent jump in farm-gate revenue over the period, thanks in large part to the commission’s sizable investment in national marketing.

Potato organizations in the state say the brand-building is a success worth maintaining.

“There is more brand recognition for Idaho potatoes than for almost anything in the country,” said Potato Growers of Idaho Executive Director Keith Esplin. “If they would quit that, in a few years potatoes would be a generic product.”

Idaho is the nation’s leading potato producer, accounting for about 33 percent of the fall crop each year, according to the Agricultural Marketing Resource Center.

When Muir contemplated leaving his 22-year corporate marketing career to lead the Idaho Potato Commission, he told commissioners and staff he would re-establish the Idaho potato as a brand. His concerns ranged from a lack of national advertising and international fresh-potato sales to a risk that Idaho potatoes were becoming almost generic despite the state’s reputation for growing them. He also said more varieties were needed.

“They knew what they were getting,” Muir said. “We are going to re-establish the Idaho potato brand as the premier brand in produce.”

In Muir’s first year, 2003, farm-gate revenue from potatoes was $536 million, down 19.7 percent from the previous year and 3.3 percent below the five-year average at the time. This year’s farm-gate revenue is $975 million, up 1 percent from 2017 and 4 percent above the most recent five-year average.

From 2003 to 2018, the commission increased its annual budget 37.6 percent, from $10.9 million to $15 million. Much of that came in 2008 in the form of a 25 percent increase in the industry-paid checkoff for marketing and research. The checkoff rose from 10 cents per hundredweight to 12.5 cents, largely to pay for national advertising. The rest of the budget increase was generated by higher sales volume.

Financial gains over the years reflect the diligence by farmers, fresh-pack shippers, processors and researchers in addition to revved-up branding, Muir said.

“Frank Muir has done an outstanding job branding Idaho potatoes,” said Aaron Hepworth, a potato farmer outside Rupert and board member for national marketing group Potatoes USA. “Some of his ideas have been just phenomenal, and with the implementation of those we’ve just seen huge gains that weren’t even anticipated.”

The Big Idaho Potato Truck’s success surprised even the ever-optimistic Muir. The semi-trailer-sized potato replica was supposed to tour the U.S. only in 2012 to mark the commission’s 75th anniversary. Instead, it has been so popular it has kept touring each spring and summer, making special appearances in parades and at sporting events and promotions. This month, it was at a regional audition for television performance show “American Idol” in Coeur d’Alene.

“There were a lot of people who brainstormed as part of this,” Muir said of the truck campaign. Local and national advertising firms, commission staff and Boise-area truck and trailer businesses made contributions to what started as a play on the longstanding postcard depicting a truck-mounted potato and declaring: “We Grow ’Em Big Here in Idaho.”

“I really liked the idea but also realized the challenges of trying to do that on that massive a scale,” Muir said.

Listing all of the things that could go wrong with a big-truck tour and laying out preventive actions and contingency plans became a focus. So did overcoming potential objections about what the public could have considered merely promotional, he said. IPC tied the truck’s appearances to fundraising for Meals on Wheels, an American Heart Association women’s health campaign and various city-specific causes including food banks.

Hepworth said that while an Idaho grower’s financial results vary year to year, efforts to brand the state’s potatoes make the industry more sustainable in the long term and “create additional demand. That is more product that needs to come from Idaho, whether fresh, processed or dehydrated.”

For example, processors J.R. Simplot Co., Lamb Weston and McCain Foods — all of which expanded or upgraded Idaho facilities recently — “want more production from Idaho so they can get a quality- or brand-associated premium price, which is what we pay the Idaho Potato Commission to do,” he said.

Muir said total Idaho potato acreage of 311,316 this year represents a 1.15 percent gain from a year ago, driven mainly by the expansion of processors.

The commission has also created global recognition for Idaho potatoes and invested heavily in research, said Dan Hargraves, who consults for the Southern Idaho Potato Cooperative. The cooperative negotiates, on behalf of member growers, annual contracts between growers and processors.

“And of late, there have been frozen potato products branded with the Idaho seal, and the commission has been instrumental working in that direction,” he said. “For the contract growers I work for, that is a really positive development. The industry is evolving and growers are evolving along with it. There has been a lot of consolidation and things are just changing. We think the commission is trying to be proactive and is addressing challenges in the marketplace.”

Americans were moving away from the potato when Muir came to the commission, said Idaho Grower Shippers Association President and General Counsel Shawn Boyle. The association and PGI advocate for the industry on legislative matters at state and national levels.

“During his time he has focused on improving that, and bringing us back to our roots,” he said.

Idaho Potato Commission Industry Relations Director Travis Blacker said there is widespread agreement among growers that having a high-profile brand is good.

“They are proud to be Idaho potato growers,” he said.

Muir, 63, grew up in Brigham City, Utah, where he was the first football player from his high school in years to earn a scholarship. Leading up to that — he played defensive end at Utah State University — keeping track of his statistics and purposefully showing interest in playing college football provided early insight into the value of communicating a clear message and a strong belief. He would refine that skill set later on a mission in Chicago for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Muir then went on to Brigham Young University, earning a dual bachelor’s degree in business management and communication in 1979 and an master’s degree in business administration in 1981.

He then worked about 2 1/2 years each for General Mills and R.T. French Co. as assistant brand manager and marketing manager, respectively. At General Mills, he earned three promotions working with some of the high-profile, consumer packaged-good brands of the era. At French, working in Idaho Falls, he helped grow a division Pillsbury ultimately acquired.

From 1986 until he came to the IPC, he worked in Fullerton, Calif., for what originally was Beatrice/Hunt-Wesson. His first job there was to turn around the La Choy brand, a line of Asian foods, sauces and prepared meals. Beatrice was acquired by a holding company and broken up, with ConAgra in turn buying Hunt-Wesson.

“What I became known as was a turnaround specialist who rejuvenated previously well-known brands and did so on limited budgets,” Muir said. Developing this specialty “gave me the creative license to think out of the box and build a brand within the structure and financial strength of a big company.”

In his last three years with ConAgra, he and his teams roughly doubled, to around $1 billion, a 15-brand portfolio including Wesson Oil, Pam, Peter Pan, Van Kamp’s and Swiss Miss without laying off staff.

“I was probably the longest-surviving marketing guy at ConAgra,” Muir said.

A creative, entrepreneurial team was a key to success, along with “an environment that promotes connection within the team and cross-functional team members from areas like marketing, sales, operations and research,” he said. “I learned that from General Mills. Always believe in connecting with your consumer on an emotional level to establish brand loyalty.”

Muir, who faced relocation within Southern California farther from his family’s home, got word from his sister in Boise that the Idaho Potato Commission was seeking a new chief executive.

Ultimately the commission extended an offer, and he said he would consider it. The commission chairman and vice chairman then met with him while he was visiting family in Utah. “That made a big impression on me.”

Muir, on arriving at the commission in mid-2003, focused on popular low-carbohydrate diets. Consumption of potatoes, bananas and apples was in decline.

“Nobody in produce was fighting back,” he said. “I don’t think they knew what to do.”

One of his early moves was to pull a new TV ad that was running in California. It showed an animated potato with a sweetened look about it. It was replaced with an ad featuring a close-up of a natural potato.

“We needed to hit: Potatoes are good for you,” he said.

National fitness personality Denise Austin helped promote Idaho potatoes for a decade starting in 2004, and the American Heart Association in 2011 — partly at Muir’s urging — certified the Idaho potato as heart-healthy. Among other initiatives, international marketing and industry relations directors were added to commission staff.

He and staff also targeted the local foods movement. Although Idaho consumers bought Idaho potatoes, the state’s small population limited that segment. The commission aimed to make sure people in other states would still seek out Idaho potatoes. Idaho’s potato market share is growing even as the movement continues, he said.

Muir said regional advertising had been the focus when he arrived. The ad focus is now national, including $3 million of the current year’s approximately $15 million budget spent to produce and broadcast two ads for early fall to late spring. The Big Idaho Potato Truck and Middleton-area farmer Mark Coombs and his Spud Hound are featured in the two national TV ads. The first ran Sept. 15 during the Boise State-at-Oklahoma State college football game on ESPN.

It and another ad are slated to run concurrently Oct. 22 through the start of April on various networks and a streaming service. Muir said this is the first year the commission filmed two spots in one year for its Big Idaho Potato Truck series — keeping the truck visible when it’s not touring.

By working with cooperating partners such as media outlets, research consultants or other marketing groups such as Potatoes USA, IPC seeks to leverage each dollar it spends into much greater long-term value, he said.

An annual advertising expenditure of about $450,000 also covers title sponsorship of the Famous Idaho Potato Bowl college football game televised nationally; the commission started that in 2011.

The commission spends 80 percent of its budget on marketing and research, he said.

Other IPC annual expenditures include around $1 million for research and $400,000 to promote fresh potatoes in more than 15 countries — “not bad for a landlocked state,” he said.

The money goes to expenses such as advertising and trade shows, and meeting with distributors and chefs. Often, Idaho’s international efforts are combined to leverage Potatoes USA’s efforts. Muir said Idaho now ships about 5 percent of its fresh potatoes to overseas, up from zero 15 years ago.

Back on the field

Muir lives in Eagle, a Boise suburb, with his wife, Cindy. They have four grown children.

He stokes his competitive spirit with running, martial arts and playing each year in the Thanksgiving Day “turkey bowl” football game with a group of friends who are fairly serious players.

“My objective is to score one touchdown so I can keep playing” the next year, he said. He’s played in 40 straight annual games.