ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 8:00 am Thursday, December 20, 2018

ARMA, Idaho — Bill and John Hartman and their families have for years run a large farm outside Parma, Idaho, on their own.

But the Hartmans are team players, too, as their participation in cooperatives indicates.

“We belong to several,” Bill Hartman said. One benefit? “Local decision-making,” he said.

The Hartman brothers belong to the supply-and-service-focused Valley Wide Cooperative, Farmers Cooperative Ditch Co. — where Bill is vice president — and have been involved in an area onion-marketing cooperative.

John Hartman said Hartman Farms purchases fuel from Valley Wide, often in small amounts as day-to-day needs dictate, “just because it’s handy next to us.”

For grain marketing, they recently started working with Pacific Northwest Farmers Cooperative in Genesee, Idaho.

Member-owned, profit-sharing cooperatives are a welcome constant in the ever-changing agricultural industry. Though they are shrinking in number nationwide and getting larger thanks to mergers, cooperatives’ importance to farmers is increasing.

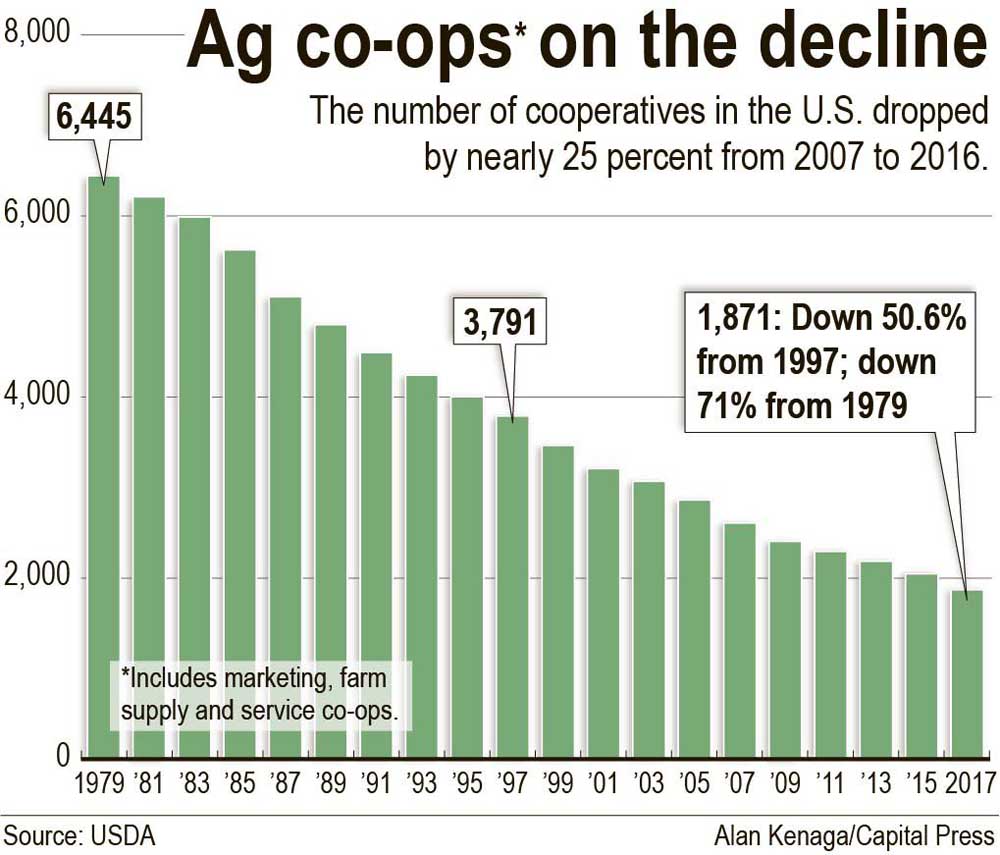

The number of supply and service and marketing cooperatives has dropped by about one-third from 2007 to 2016 while the combined net business volume for the 1,953 that remain rose by 28.5 percent, USDA reported. There were 1,871 cooperatives last year, down from 6,736 in 1976.

“And the projections are that there will be even fewer over the next few years,” said Ken Blakeman, general manager of CHS Primeland in Lewiston, Idaho. “It mirrors the changes in our production-agriculture world.”

The trend toward fewer, larger players includes farming in general. An example is when economic or other factors prompt sons and daughters not to return to their family’s farm, which in turn rents or sells its ground to a neighbor, he said.

“You don’t see too many people getting smaller, and it’s tough,” Blakeman said.

Because of the shrinkage in the number of farms, USDA found there has been a nearly 23 percent drop in cooperative memberships from 2007 to 2016.

As many farms get bigger, Blakeman said, “there is a need for cooperatives to update facilities and build things that are bigger and faster, to take care of today’s and tomorrow’s high-volume producers.

“We really had to recapitalize the industry,” he said. “One of the challenges to the small, independent cooperative is access to capital. You need to build for the producers’ need and scale.”

Purdue University agricultural economist Michael Gunderson said that as cooperatives’ member base gets smaller as the number of farms declines, those farmers who remain are different. “Even two or three generations ago, most farmers looked pretty similar and farms had similar acreage, crops and needs.”

Today’s larger farms can be very different from one another with much different needs, he said, “so the opportunity for a cooperative to serve them efficiently could be pressured.”

For example, some farms are big enough to run their own chemical application equipment instead of leasing cooperative-owned equipment as needed.

As older farmers retire and new decision-makers take over, “that loyalty and that relationship may come under pressure during that transition,” Gunderson said. “Cooperatives are paying attention to their marketing programs, and how to build programs meeting the needs and wants of today’s farmers.”

The tight labor market is one factor driving cooperatives to merge, said Hood River Supply President and CEO Pat McAllister in Oregon. As co-ops get larger, they often need fewer middle and upper managers.

Jerome, Idaho-based Valley Wide Cooperative has grown twenty-fold since forming 20 years ago through the merger of two small co-ops. CEO Dave Holtom expects more growth and change.

“As our customers change, we have to change to remain relevant,” he said.

Holtom expects continued growth for Valley Wide — likely by around 30 percent in the next five years due to mergers, he said — amid challenging market conditions. Competitors include large multinational companies and newer businesses using an online, price-discovery model that adjusts prices for the size and needs of individual customers.

Valley Wide formed in 1998 when the Menan and Madison cooperatives merged in eastern Idaho. It now has about 900 employees and operations in 40 communities in Idaho, Oregon, Washington, Wyoming, Utah and Nevada. Members grow about 200 different crops compared to four at the outset 20 years ago.

“We have tried to incorporate the history of the cooperatives that have merged into us, the legacies, recognizing their unique place in their communities and the cooperative system,” Holtom said.

All of the mergers aimed to maintain Valley Wide’s influence and market relevance, he said. They also provided some risk aversion by broadening and diversifying geography, business units and the crop portfolio.

Annual sales exceed $500 million and are tracking about 10 percent higher than a year earlier, Holtom said. All segments — agronomy, retail and energy — are contributing.

“Because of our diversity, customer base and talent, I think we will be successful,” he said. “We are going to be here for a long time.”

Cooperatives remain effective for reasons including personal service and just-in-time delivery at brick-and-mortar locations, transparency, customer input on business direction, and member profit-sharing, Holtom said.

Adam Clark, who farms and raises cattle near Menan, Idaho, and chairs the Valley Wide board, said cooperatives provide value beyond members eventually being repaid a portion of their purchase volume and potentially building equity.

“There is member input as well, and it helps,” he said. “When people tell me something, I can take it back to the boardroom. And a co-op is a little more service-oriented in that it takes feedback directly. The people on the board are using these products.”

National Council of Farmer Cooperatives spokesman Justin Darisse said the group lately adds one or two co-op members per year. They join because they want to tap its services, although “the pool of organizations that make up that membership is not that large.”

“Trends that impact agriculture, and impact the farmers and ranchers themselves, also play out on the co-ops,” he said. “Mergers in co-ops and the consolidation there reflect what we have seen generally among the producers themselves.”

Darisse said prolonged lackluster pricing for many commodities poses concerns throughout agriculture. “Co-ops are an important way to bridge that a little bit” by helping producers receive a slightly higher price for commodities or reduce some net costs, he said.

Oregon, Washington and Idaho have even merged their states’ cooperative advocacy groups.

The Idaho Cooperative Council this month joined the Northwest Agricultural Cooperative Council, formed in the past year when the Washington and Oregon councils merged. Blakeman said the states grow many of the same crops, and “we have much more in common than we have that is different.”

So far within NWACC, there has been no loss or dilution of Oregon issues, Hood River’s McAllister said. NWACC fields separate lobbyists in Oregon and Washington, and continues projects each state worked on before the merger. The council emphasizes education.

NWACC Executive Director Ben Buccholz expects a smooth transition as Idaho integrates.

“They have a pretty strong advocacy arm and a pretty strong educational arm,” he said of the Idaho council. “We may try to pick up on some of the educational offerings. They do a big FFA student and Legislature lunch in January in Idaho. That might be something we try to do in Washington.”

College students tour cooperatives in the summer through an Oregon State University-tied program the state’s council initiated. Buccholz said NWACC aims to replicate it with Washington State University next summer. Another Oregon-initiated program, an FFA quiz on cooperatives that awards scholarship money, is also targeted for Washington.

Council-led education can help young people understand that cooperatives are great places to work and offer competitive salaries, he said.

“What we are trying to do is cultivate the next generation of employees and of cooperative owners,” Buccholz said.

Even with all of the changes, the bedrock value of every cooperative remains, because members have a voice in its operation, advocates say.

Cooperatives’ ongoing value can be seen in the more-than-century-old Farmers Cooperative Ditch Co., in the Parma, Idaho, area.

Bill Hartman said it functions as an irrigation district or canal company with water rights, infrastructure and a per-share assessment, “but its irrigators are board members and directors. Local irrigators can change bylaws and the way the company is run by vote.”

Farmers Cooperative Ditch earlier this year partnered in a sizable settling-pond project designed to improve water quality.

“A group of directors chose to move that direction, and we pretty easily got that accomplished,” Hartman said.