ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 7:30 am Thursday, January 9, 2020

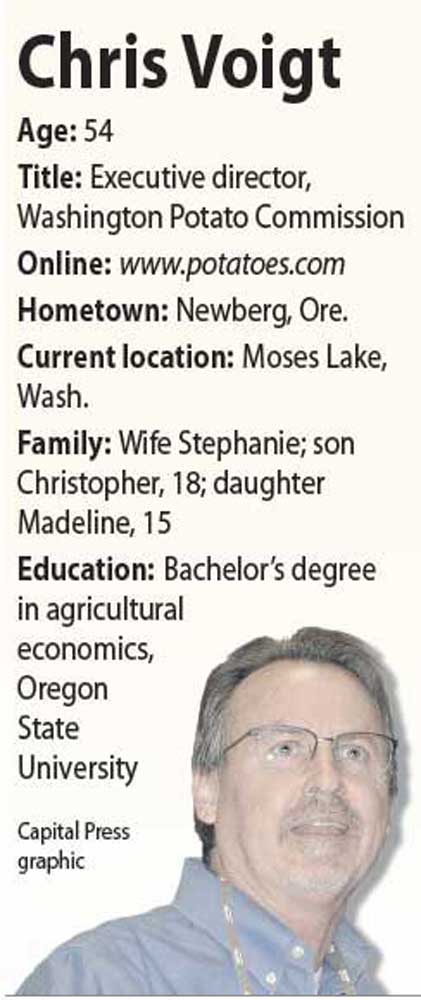

MOSES LAKE, Wash. — Chris Voigt has gone on an all-potato diet for two months, flown 1 million airline miles and ridden a bicycle from Seattle to Portland.

And he did it all for Washington potatoes.

Voigt, 54, is with the Washington Potato Commission, where he’s been executive director since 2005. Using a budget of about $3 million, he works with a board of farmers to enhance trade opportunities, fund research and represent the state’s 250 potato growers’ interests in Olympia and Washington, D.C.

During his career he previously worked with farmers who grew many other crops — cotton, soybeans, corn, grass seed, vegetables, lettuce and tree fruit — but he says he always gravitated back to potato farmers.

“They were just so progressive,” he said. “They were always willing to try new things to try to become more efficient, more sustainable. I just liked that atmosphere.”

They like him, too.

“Chris lives potatoes,” said Grant Morris, a Pasco, Wash., farmer and commission board member. “It’s easy to get things done as a commissioner when you have someone to follow into battle like Chris.”

Morris called Voigt an “idea man,” thinking of different ways to further interests of the state’s farmers and the entire industry.

“Having someone that can attack a problem head-on from a conventional standpoint is good most of the time, but we face many issues regularly that need a slightly more creative solution,” Morris said.

Because of Voigt and the commission staff, Washington’s farmers are leaders in research, legislative issues and public outreach, Morris said.

“None of us would be able to farm without those things,” he said. “It has been and continues to be vital to our future.”

Washington’s potato crop was valued at $788 million last year. In 2018, potatoes were the third most valuable crop in the state, behind only apples and wheat.

Potato farmers set the commission’s agenda, Voigt said. That includes taking the lead in organizing legislative tours and funding research and promotions.

They even helped develop an Emmy Award-winning TV show, “Washington Grown,” to reach consumers, but with a twist.

“They said, ‘Let’s back off on potato promotion and just promote agriculture,’” he said. “It was like, ‘Whoa.’ To hear that come from a potato grower’s mouth, to really put the common good of all agriculture above promoting our own crop, I think that says a lot about the people I work with.”

Voigt grew up in Newberg, Ore. His father worked at a pulp and paper mill, while his mother was a stay-at-home mom to six children, with Chris being the fifth.

He describes himself as a “town kid,” but “all my friends were farm kids.”

In high school, Voigt became involved in FFA. He loved the parliamentary procedure competition, which got him hooked. He entered his first public speaking competition his junior year of high school.

“At the district level, I took 11th out of 12, and probably would have taken 12th, but there was someone who was actually more nervous than me and threw up during their presentation, and didn’t finish their speech, so that automatically bumped me up a spot,” he said.

Voigt’s adviser pushed him to get up in front of the class each week and speak extemporaneously on a topic. He came in second the next year — and was elected the state FFA president.

“That was a fabulous experience,” he said.

Voigt traveled the state putting on presentations and staying with host families afterward.

One visit still moves him.

The host family’s son had died in a car accident, and Voigt would arrive the day after the funeral. An FFA adviser had tried to give Voigt a heads-up, but they weren’t able to connect before he left with the family.

When Voigt arrived at their home, he was struck by how quiet it was.

“So during dinner, I’m laughing and telling stories and talking about my family, asking questions about them and they’re telling me about their kids,” Voigt recalled. “Just before bed, they say, ‘Oh, we have another son, but he passed away last week.’”

Voigt felt terrible, fearing that he had unwittingly been insensitive.

“The next day, as I was leaving, the mom said, ‘Thank you. We needed last night,’” he said, a hitch in his voice. “Those types of life experiences, at a young age, they really had an impact on me. It solidified my love of agriculture.”

Voigt studied at Oregon State University, expecting to major in agricultural education, but then switched to agricultural economics.

After graduating, he was working as a product manager for a small chemical company that was closing down its agricultural division.

He started thumbing through the potato magazines in which he had purchased advertisements to see if he’d canceled them, and came across an ad for a job at Potatoes USA, then the National Potato Promotion Board, as a liaison between growers and the organization.

He got the job and moved to Denver, Colo., working for six years. He then worked for the Colorado Potato Administrative Committee for three years before joining the Washington commission as its executive director.

Voigt considers himself fortunate that his wife, Stephanie, handles family life while he’s traveling. They have two children, Christopher, 18, and Madeline, 15. He and Stephanie will celebrate their 20th wedding anniversary in February.

Potatoes were even involved in how they met.

He was working for the potato promotion board in Denver while Stephanie was working for Monsanto Naturemark, the first genetically modified potato.

They met at a meeting of potato growers in Fargo, N.D.

“We started dating at potato meetings across the country,” Voigt said.

Their first kiss was at the Washington Potato Conference in Moses Lake, he said.

After a year and a half, they had a decision to make: Which person would move to join the other? He lived in Denver and she was in Idaho.

“We did what every mature couple does — we bet on a hockey game,” Voigt recalled.

The Idaho Steelheads were playing a minor-league hockey team from Colorado. Which team won the game would determine where the couple would live.

“About a month and a half later, my U-Haul showed up in Boise,” Voigt said.

Voigt maintains an active lifestyle. He is an avid skier, starting when he was 6. His kids have skied since they were 3, and the entire family went night skiing Jan. 2.

“Sometimes I wonder what I like more, the actual skiing or just the chairlift ride up, because it’s quality one-on-one time,” he said.

Voigt and his family also surf, backpack, whitewater raft, bike, fly fish and kayak.

“Sometimes I kayak to work,” he said.

He lives a block from Moses Lake. He carries his kayak to the water and spends the next hour paddling 2 miles to the office, which is also near the lake.

In spite of — or because of — his active lifestyle, he tends to be injury-prone. Photos on his Facebook timeline provide evidence.

Over the summer, he separated some ribs surfing. He hurt his shoulder while skateboarding in November. And he hurt his knee skiing in December.

His latest sport is longboarding.

“I had a blast with it, but I think there was a 12-month period where I broke my wrist three times,” he said of his oversized skateboard.

Voigt shrugs off the injuries.

“I just, like, get out and do stuff and sometimes fate isn’t on my side,” he said. “I think it’s part of the kid in me. It’s just fun. I love the feel of wind in your hair and flying down a hill, whether it’s on skis, surfing or skateboarding. It’s all fun stuff. I just like adventure. Sometimes, unfortunately, it leads to mishaps.”

Demand for Washington potatoes is “red-hot,” particularly for french fries and tater tots in Pacific Rim countries and the Middle East, a new market for the state’s growers.

“We want to expand, our customers are on rations — they have been for the past five years,” he said. “We just can’t meet the demand.”

The big challenge, Voigt said, is how to grow more potatoes and expand processing capacity.

“That’s actually pretty exciting,” he said.

There are three ways to do it, Voigt said:

• Find more water and cost-effectively deliver it to create more irrigated farmland.

• Boost yields by investing in research on better genetics and management.

• Shorten rotations. “Right now, you can only grow potatoes once every four years, maybe once every three if you’re lucky,” Voigt said.

Grow any more frequently than that and too many pathogens or pests can build up in the soil, he said.

The ability to shorten potato rotations to every three years through better management would increase production 25% and encourage the region’s processors to expand, creating more jobs, Voigt said.

“It’s an opportunity to grow the economy in a rural area and meet customer demand,” he said.

He has promoted Washington potatoes in unusual ways, including taking part in a bicycle ride between Seattle and Portland.

But in 2010, Voigt captured media attention by going on an all-potato diet. He ate 20 potatoes a day for 60 days.

The point was to prove that potatoes are healthful. It’s the extras — cheese, bacon, butter and sour cream — that give them their reputation for being fattening, he said.

The biggest concern doctors had at the time was that Voigt wouldn’t get his daily dose of essential fatty acids. But french fries supplied them, he said.

He lost about 21 pounds, and his cholesterol and glucose levels improved over the 60 days.

He still occasionally hears from people about the diet.

“It still resonates,” he said.

Voigt would like to do one more big potato promotion, on the same level as the diet.

“I want to see if it’s possible,” he said. “That’s what I want to do before I retire to the big potato storage in the sky.”