ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 7:00 am Thursday, September 17, 2020

JORDAN VALLEY, Ore. — In a time when some ranchers struggle to come up with a family succession plan for their operation, Mike Hanley considered himself lucky.

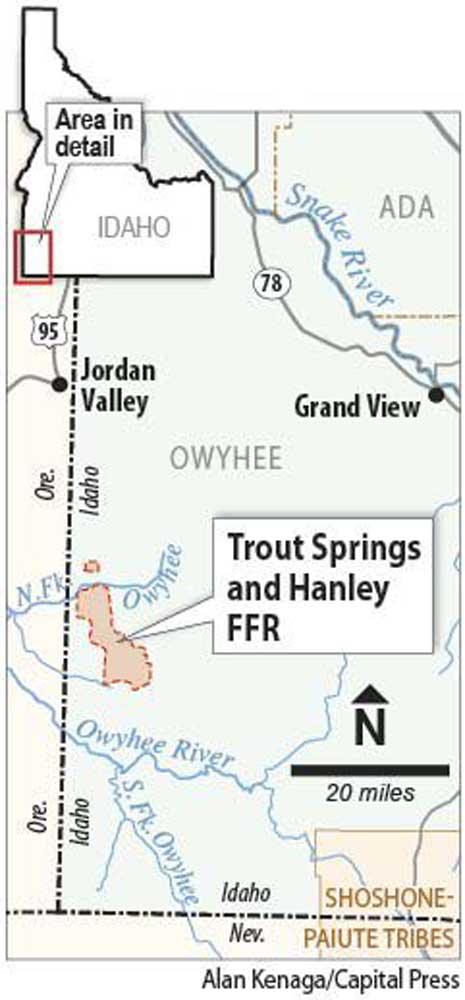

His daughter and son-in-law, Martha and John Corrigan, were keen to expand their cattle operation by taking over Hanley’s ranch in Jordan Valley, Ore., and the associated grazing allotments in nearby Idaho.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, however, the 30,000 acres of grazing allotments were off-limits to the Corrigans.

Hanley had lost his permit to graze on federal property, BLM officials said in a final 2017 decision, thus the ranch had lost its “preference” for livestock access to nearby public lands.

Under the federal government’s grazing program, such “base” properties near federal property are awarded preference to obtain grazing permits.

Without the forage growing on surrounding federal property, Hanley’s private 1,900-acre ranch would be uneconomical for the Corrigans to run.

“It has the potential to destroy the legacy of generations,” said Hanley, who’s lived on the property since 1949.

The BLM’s elimination of the Hanley ranch’s grazing preference was upheld by a federal judge earlier this year, but the family is now challenging that ruling before the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The case has drawn the attention of ranchers across the West who have traditionally believed federal grazing preferences are tied to “base” ranch property regardless of permit status.

Without that certainty, ranching families fear their legacy is vulnerable to termination at the stroke of a BLM official’s pen.

“It affects every permittee on Western public lands,” Hanley said. “A whole culture and way of life in the American West is under the gun right now.”

The BLM claims that Hanley lost his grazing permit due to an “extensive record of noncompliance” with regulations dating back to the early 2000s.

Hanley, on the other hand, argues he was sabotaged by environmental activists opposed to public lands grazing who cut fences and left open gates to ensure his livestock would venture onto rested pastures.

“I think it was ecoterrorism,” he said.

After losing the permit, Hanley opted to lease the base ranch to the Corrigans rather than continue his administrative struggle with BLM. However, the couple was denied a grazing permit by the agency because the private property no longer had any preference.

The agency also accused the family of “permit laundering” to get around regulations, said Linda Hanley, Mike’s wife. “It was a total shock to us all.”

The BLM’s actions are troubling because it’s circumventing the separate bureaucratic process for eliminating a ranch’s grazing preference, which is more involved and rigorous than simply not renewing a grazing permit, said Alan Schroeder, the family’s attorney.

“They invented the theory that somehow the preference evaporated when they didn’t renew it,” he said of the permit. “It’s just a backdoor way to cancel preference.”

The agency is simultaneously eroding the due process rights of families like the Hanleys and Corrigans while increasing its own power, Schroeder said.

“BLM wants to maximize its discretion to terminate preference,” he said.

The implications for other ranchers are worrisome, Schroeder said.

If a landowner leases his base property to another rancher who then obtains but loses a grazing permit, for example, the underlying land’s grazing preference is also extinguished, he said.

“They just canceled the preference attached to my property without me being the bad operator,” Schroeder said. “Just because one person is a bad operator doesn’t mean the other is.”

It’s possible to envision more mundane scenarios in which a permit expires due to bureaucratic mistakes or delays, allowing the BLM to terminate the property’s grazing preference without additional due process, he said. “Just don’t renew the permit.”

In a response to questions from Capital Press, a spokesperson for the BLM issued a statement saying the agency’s actions “were first upheld in full by the Interior Board of Land Appeals and later by the District Court of Idaho.”

The plaintiffs have “exercised their right to appeal” and the “BLM has no further comment,” the agency said.

For the Western livestock industry, which is often dependent on public lands, the prospect of BLM further undermining the concept of grazing preference is alarming.

The Owyhee Cattlemen’s Association and Idaho Cattle Association submitted a court brief urging a federal judge to overturn the BLM’s decision in the Hanley and Corrigan case.

“This new interpretation turns a fundamental aspect of the Taylor Grazing Act on its head,” the brief said, referring to the landmark 1934 law that established the federal grazing program. “In so doing, the BLM decision threatens to subvert the entire system of public land livestock grazing that the act enabled and guaranteed.”

If it becomes easy to eliminate a ranch’s grazing preference, the connection between private lands and federal property is weakened to the detriment of the local community, said Bob Skinner, a rancher near Jordan Valley and president of the Public Lands Council, a national organization that advocates on behalf of ranchers.

“They could just upend the entire economy out here,” he said.

Cattle are easy to transport across great distances these days, so it’s conceivable someone could simply outbid local ranchers for access to federal grazing allotments, Skinner said.

Local ranchers spend heavily on improvements to their allotments, which are often interspersed with their private ground, Skinner said. The possibility of losing that investment is tremendously disruptive.

“The Taylor Grazing Act was enacted to stabilize the livestock industry,” he said. “This is not stabilizing the industry.”

Organizations representing ranchers who hold nearly 18,000 grazing permits and leases on 154 million acres of BLM lands complain the agency has already greatly undercut the way grazing preferences are supposed to work.

The damage stems from 1995 regulations enacted by the Clinton administration, under which “preference” was defined simply as a “priority” for obtaining permits without referring to cattle numbers.

Traditionally, preference also referred to a specific number of animal unit months, or AUMs, to which the base ranch was entitled. The agency charges $1.35 per AUM and earned $13.3 million in fees during its most recent fiscal year.

An AUM represents the amount of forage a cow-calf pair can eat in a month. Active AUMs determine how many cattle can be turned out, while suspended AUMs represent potential capacity that must go unused until range conditions improve.

Under the BLM’s 1995 rules, the AUMs are determined according to the permit, which is typically seen as less stable than preference.

Unless the grazing preference spells out the associated AUMs — both active and inactive — the value of the ranch itself is diminished, said Jeff Maupin, a rancher near Riley, Ore., and former president of the Harney County Stock Growers Association.

“When you purchase the ranch, there’s a value on every AUM,” Maupin said. “How can they just take that away and not compensate you for it?”

“You have a mortgage on it, you can borrow money against it,” said Erin, his wife. “We’re not just leasing it.”

The difference may seem arcane, but for the Maupins and other public lands ranchers, grazing preferences ensure that local landowners have a long-term bond to the public allotments.

“They’re destroying the private property aspect and creating a lease,” Erin said. “It can just be people without a stake in the resources here.”

“People who don’t have a vested interest in the community,” Jeff added.

Twenty years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the 1995 grazing regulations but the lawsuit involving the Hanleys and Corrigans may be an opportunity to again challenge their validity, said Brian Gregg, a public lands attorney with the Mountain States Legal Foundation.

The family’s experience could demonstrate that without specific AUMs tied to grazing preference ranchers’ grazing privileges aren’t being “adequately safeguarded” as required by the Taylor Grazing Act, he said.

“They have passed regulations that contradict the statute,” Gregg said. “You have a priority, but a priority to what?”

Under the BLM’s theory that preference can be extinguished with the permit, preference becomes a “useless appendage” that can be canceled as easily as a driver’s license, he said. “Imagine trying to get a loan based on your driver’s license. No one would do that.”

For environmental groups critical of federal grazing oversight, the complaints about preference are symbolic of a greater problem in the livestock industry.

Ranchers are basically arguing they should have access to federal allotments no matter how much they abuse the land, said Katie Fite, public lands director for the Wildlands Defense nonprofit group.

“This cuts to the core about what is wrong with the public lands grazing system, which is there is so little accountability for the livestock industry,” she said. “The ranchers see themselves as local land barons. They see themselves as having an inviolable right to graze the public lands.”

Arguments about the BLM undermining stability is just another way for the “same old good old boys” to try to discourage competition, Fite said.

“They want to cement themselves and their power in place,” she said. “What they want to see is a step toward privatization of the public lands.”

The Western Watersheds Project nonprofit submitted a court brief supporting the BLM’s position and believes the federal judge got the Hanley ruling right.

“Grazing is a privilege, it’s not a right. It can be revoked at any time,” said Erik Molvar, the group’s executive director. “If you have your permits revoked, there should be no preference.”

The Hanley and Corrigan families “tried to pull a fast one” but didn’t get away with it and the ruling should send the message to other ranchers: Bad actors should clean up their act, Molvar said.

“Every rancher should be aware of this possibility and abide by the terms and conditions accordingly,” he said. “They should be careful not to abuse the land or they might get kicked off.”

The Hanleys and Corrigans have a different perspective.

Mike Hanley said the situation stems from his long-running disagreements with the BLM.

“If you dare fight the agency, you get a target on your back,” he said.

“They can litigate you out of business,” added Linda, his wife.

John Corrigan, his son-in-law, said he has little choice but to depend on public lands to grow his business, much like other families in a region comprised mostly of federal property.

“These outside businesses are totally supported by the agricultural economy,” he said. “Once the rancher leaves, there is no economy.”