ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 7:30 am Tuesday, December 29, 2020

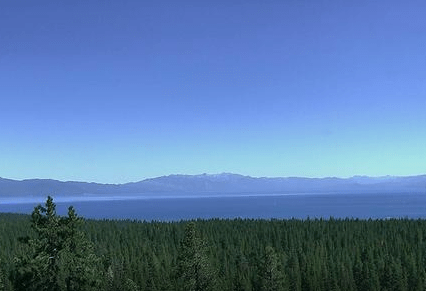

Oil giant BP announced in December it bought a controlling stake in Finite Carbon, the largest U.S. developer of forest carbon offsets.

The deal is part of a growing market — the business of paying landowners not to cut down trees.

It works like this: A business that needs to offset its carbon emissions by 10,000 metric tons can pay a landowner to store 10,000 metric tons of carbon in a forest.

The growing market, experts say, is contentious in the forestry industry because as companies rush to offset their emissions, trees may have more value standing than cut down — good for landowners but bad for mills.

“People should be able to do what they want with their land. But they should also be concerned with ensuring manufacturing industries have enough supply of wood fiber,” said Nick Smith, spokesman for the American Forest Resource Council.

Smith said mill owners are concerned that setting aside forests for carbon offsets will reduce the fiber supply, causing some mills to close and others to pass higher costs on to consumers.

“I think we’re a long way from limiting fiber supply,” said Sean Carney, president of Finite Carbon. “But I see the long-term issue.”

Many landowners, in contrast, are excited about the opportunities.

BP, one of the world’s largest producers of carbon dioxide, invested $5 million in Finite Resources, the parent of Finite Carbon, in 2019. Now, with its majority stake, BP is planning to offset its emissions and betting other companies will do the same.

Finite Carbon connects landowners with businesses that pay a fee per ton for carbon permanently stored in the forest. The company takes many factors into account when determining the value of a particular forest, including tree species, geography and potential risks.

“Not all trees are created equal,” said Carney. Pine trees, for example, store less carbon than hardwood trees.

Many registries require forests be set aside for 20, 40, 100 or 125 years.

There are two main offset markets: compliance and voluntary. An example of a compliance market would be California’s cap-and-trade program.

But University of California-Berkeley researchers say there is “huge, growing interest” in voluntary markets.

Carney estimated that in compliance markets, landowners get paid about $12 per ton, and in voluntary markets, at least $10 per ton.

Finite Carbon has primarily been involved in compliance markets so far, but the company plans to expand into the voluntary market.

Small-scale landowners have traditionally faced barriers to entry into the offset market because assessing a forest is expensive. Finite Carbon has mainly worked with landowners with 20,000 or more acres.

But with BP’s financial backing, it will work with landowners with as few as 40 acres starting in early 2021.

Offset markets face many challenges, experts say. For example, setting aside a forest to sequester carbon doesn’t guarantee it won’t burn in a fire, as demonstrated when Oregon’s Lionshead Fire this year almost entirely engulfed the largest forest in the state dedicated to sequestering carbon.

“We need to remember forests set aside only for carbon are as dynamic as any others. If that forest burns down, you didn’t keep that carbon out of the atmosphere,” said Smith of AFRC.