ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 12:45 pm Wednesday, March 17, 2021

The fuzzy future of Oregon politics east of the Cascades went public last week: No diagrams, charts, data — really nothing tangible at all to show how new legislative and congressional districts will be drawn.

“We don’t have any maps,” said Rep. Andrea Salinas, D-Lake Oswego, chair of the House Redistricting Committee. “We don’t have any numbers from the census.”

Salinas and her Senate counterpart, Sen. Kathleen Taylor, D-Milwaukie, said they were making a good faith effort to hold the legally required 10 public hearings on new political maps.

Maps that don’t exist — at least, not yet.

The hearings are collateral damage from the constitutional car crash headed to the Oregon Supreme Court.

The once-a-decade process of rebalancing populations in legislative and congressional districts is a smolderingly hot political wreck. Any fix isn’t expected earlier than autumn.

Like so many things over the past year, COVID-19 is the main problem.

In normal times, the U.S. Census counts people every decade, in years that end in zero.

The Legislature gets detailed Oregon data by April 1 of the following year. Lawmakers have until the end of their session on July 1 to get maps of 30 Senate, 60 House and either five or six congressional districts to the governor.

If they can’t agree on a redistricting plan, the secretary of state takes over the mapmaking with an Aug. 15 deadline.

But these are not normal times.

COVID-19 crippled the census count. The Legislature received no data. No maps are being drawn for the governor. There’s no dispute for the secretary of state to resolve.

The census officials in Washington, D.C. have been saying sorry for months. But given all the upheaval in their work, they now say data to draw districts won’t get to Oregon until Sept. 30. That is six months late and well beyond constitutional and statutory deadlines.

To employ an overused term during the current pandemic, the situation is “unprecedented.” Translation: Nobody knows what to do because its never been done before.

Adding to the drama: The official population numbers are expected to earn Oregon a sixth congressional seat, its first in 40 years. The new district will have to be shoehorned into the existing congressional map.

The Legislature has a “back to the future” solution. It’s asking the Oregon Supreme Court to set the deadlines aside, reset the clock, and give lawmakers another shot at redistricting when the data arrives in the fall. A special session of the Legislature would meet to approve the work.

Secretary of State Shemia Fagan supports the idea.

The Legislature wants up to 90 days after the data arrives to create the maps.

Fagan does not support that timeline.

Pushing redistricting into December would be cutting things close, Fagan has said. Any hitch and there could be no maps when candidates are supposed to start filing for the offices in January. As the state’s official election referee, she might have to step in.

House Speaker Tina Kotek, D-Portland, and Senate President Peter Courtney, D-Salem, filed a petition with the Oregon Supreme Court this week to stop Fagan from drawing her own maps.

Fagan wants the Legislature to draw districts using alternative data to the U.S. Census. The Oregon constitution doesn’t explicitly demand redistricting be done with the census numbers.

But it always has used the census, lawmakers say. Doing things differently than how its been done for more than a century would be a surefire way to tangle with federal courts wanting to ensure Oregon was following civil rights and voting rights laws.

While the court sifts through the paperwork, the Legislature is planning/hoping/praying the Oregon Supreme Court will pick its solution. A way to move things along in advance would be to hold the ten required hearings — two in each of the current five congressional districts.

Which brings things back to COVID-19. The usual “road trip” of lawmakers to districts to hear from voters aren’t happening this year because of COVID-19. All 10 redistricting hearings will be virtual.

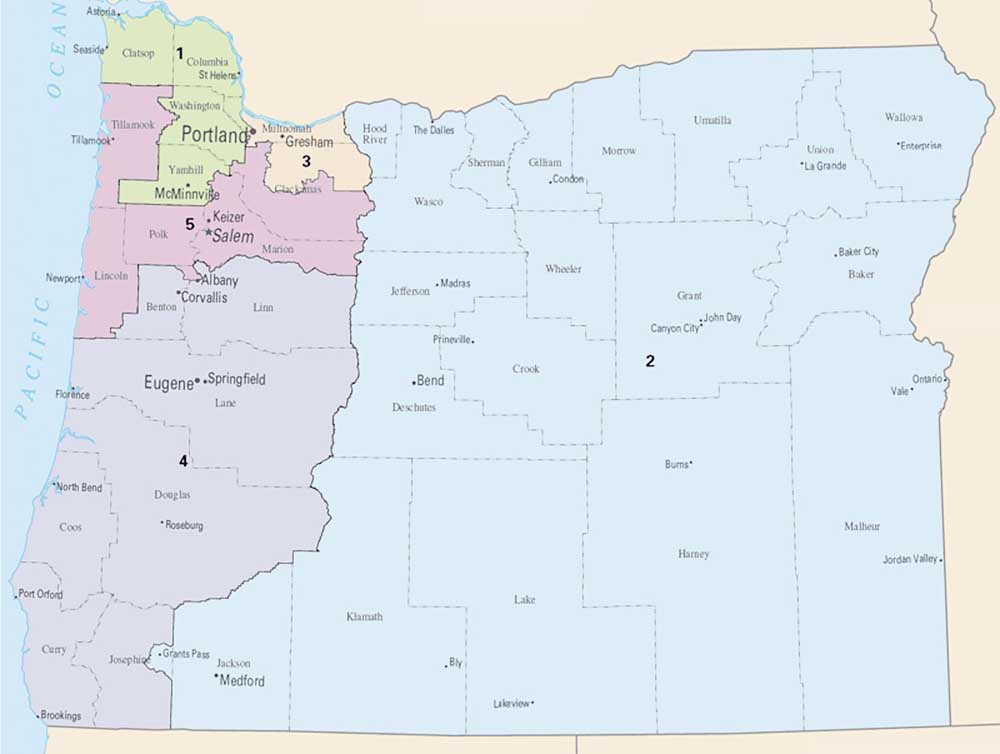

Wednesday’s hearing was Congressional District 2, a nearly 70,000-square-mile expanse that share borders with California, Nevada, Idaho and Washington. Anyone living east of the Cascades, plus a chunk of the southwest part of the state, lives in the 2nd District.

All four of the other congressional districts are represented by Democrats. The 2nd is solidly Republican, with freshman U.S. Rep. Cliff Bentz, R-Ontario, in the seat.

The hearing Wednesday would require something of a technical miracle. Video testimony expected from Wallowa County, Bend, Medford, Klamath Falls and several other spots in the district taxed the Legislature’s internet capabilities. Balky phone lines, echoing microphones, stuck mute buttons and more led to frequent silent spots. Many of the people who signed up to testify either couldn’t get through or gave up prior to their turn in the queue.

Two who signed up discovered they lived in other congressional districts.

One caller wanted to know why Wallowa County had been left off a map of Greater Idaho.

Some of the panel members squinted “what?”

Rep. Daniel Bonham, R-Dallas, finally piped-up to explain the caller’s query was about a theoretical secession of much of eastern Oregon to form “Greater Idaho” with the neighboring state to the east.

Bonham even helpfully added that some maps circulating for the mythical “Greater Idaho” state did not include Wallowa County, though he wasn’t sure why. With the mystery aside, the discussion could return to Oregon.

For over an hour, the committee heard three main themes: The district was much too large. It included different communities with different identities, and in the case of Malheur County, a completely different time zone (Rocky Mountain Time).

Finally, the desires of people in the district were too often ignored in the capitals of Washington and Salem. How they were ignored depended on each testimonial.

In a written statement, Umatilla County Commissioner George Murdock struck a note between hope and resignation over the likely outcome of the process.

“My greatest concern is that our district could be gerrymandered in order to further diminish representation for a portion of Oregon that reflects ideology, values, and interests much different than the remainder of Oregon,” Murdock said.

New districts should “geographically make sense” to retain an Eastern Oregon voice in Washington and Salem.

“If Oregon gets a new seat, we are not naive enough to expect more representation for Eastern Oregon but we would like to retain what we have,” Murdock said.

Nathan Soltz, chairman of the Democratic Party of Oregon’s 2nd Congressional District Committee, said the sparse population and vast landscape made it difficult for communities to feel any mutual connection.

“You can drive from Medford to Enterprise — about 10 hours — and never leave CD2,” he said.

Ann Snyder of Ashwood in Jefferson County agreed that the current boundaries created an oversized area with too many acres and not enough people.

“District 2 is geographically too big for one person to accurately represent,” Snyder said in written testimony. “Trying to cover an area from Medford to Hood River and the Cascades to the Idaho border is too much, and the people are too diverse.”

Brad Bennington of Jackson County said lawmakers needed to listen more to rural voters.

“There is more to the state than just Portland and Salem,” he said. “There are a lot of people who feel they haven’t been heard.”

Bennington said he would give the legislators the “benefit of the doubt” in drawing political maps.

“Democrats can keep themselves in the supermajority until the day the sun doesn’t come up,” he said.

But Barbara Klein of Ashland said she experienced the opposite feeling. She wanted congressional and state districts that would have more in common with the arts town at the foot of the Siskiyou Mountains.

“Don’t separate us from Bend, Deschutes County,” she said. “Communities that have shared values, a bit more left leaning.”

Todd Nash of Enterprise said it would be difficult to draw political maps with so little population to pool into a district.

“We have about 320 acres per person,” he said.

Craig Martell of Baker City said proximity and highway connections should guide the grouping of communities in districts.

“Baker City and La Grande, only 44 miles apart on Interstate 84, belong in the same district,” he wrote. “As lines are currently drawn, Senate District 30 is a grotesque gerrymandered monstrosity.”

Mimi Alkire of Deschutes County represented the League of Women Voters, which supports the creation of an independent redistricting committee to draw the lines instead of lawmakers.

“Redistricting has been used to restrict and dilute voters,” she said. “Voters should choose their representatives, not have representatives choosing their voters.”

Resolutions have been introduced in the Legislature to move to a commission like those already used in California and several other states. Several speakers endorsed such a plan. But even if approved by the House and Senate, the change to the state constitution would need voter approval. Any change wouldn’t occur until the 2031 redistricting.

Joanne Mina, volunteer coordinator for the Latino Community Association, based in Bend, said it was important for lawmakers to make sure that the census numbers were a complete count.

“The Latinx population has grown from a few thousands in the 90s to over 20 thousand strong across all of Central Oregon — our region is united by commerce, culture and values,” she said. “Central Oregon is not what it used to be, we are more vibrant, enriched and bold because of all the people that make up our community.”

At the end of the evening, Salinas, chair of the House committee, said the gathering of so many people from so many places had been time well spent.

“A robust debate,” she said.

The video ended. The committee will hold a second hearing on Saturday, March 20, at 1 p.m.