ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 10:11 am Monday, June 12, 2023

Since California beekeeper Valeri Strachan-Severson started breeding honeybees, she has seen a marked difference in the health of her hives. Her bees are stronger, more hygienic and rarely experience American foulbrood, a deadly disease.

“There have been many advantages to doing the breeding program,” said Strachan-Severson.

The beekeeper learned a crucial piece of her breeding program – how to instrumentally inseminate honeybee queens – from Susan Cobey, a research associate at Washington State University and owner-operator of Honey Bee Insemination Services.

“She is really passionate about working on the bees and having strong diversity and strong traits,” Strachan-Severson said of Cobey.

Alongside fellow WSU researchers, Cobey has been working for years to breed a better U.S. honeybee more capable of warding off pests and diseases, flying in cold weather, producing more honey and surviving harsh winters.

The breeding program is centered around inseminating “starter” queen bees with semen from drones, or breeding males, that have desirable traits. Honeybee producers can then introduce the starter queens into their hives, improving the gene pool.

In addition to working with U.S. genetic lines, Cobey also imports bee semen from Europe and Asia. It’s simpler and less risky to import semen than live bees, said Cobey. The day she talked to Capital Press, she was packing for a trip to Italy and Slovenia to collect semen from honeybee subspecies.

In different countries, honeybee subspecies have evolved with different characteristics and behavior, said Cobey. For example, Italian bees tend to build bigger broods, while bees from Slovenia, the Republic of Georgia and Kazakhstan are more cold-hardy, meaning they can fly and pollinate crops in cooler weather.

Cobey has imported semen from drones of these international subspecies and instrumentally inseminated U.S. queen bees, resulting in stronger genetic lines with desirable traits. She said the first-generation crosses show hybrid vigor, or improved function, and subsequent generations are also healthier.

“The first cross is pretty rockstarish. But they do maintain higher productivity and health over generations,” said Cobey.

Breeding for some characteristics is challenging. For example, Cobey said a “suite of traits” are required to build resistance to parasitic varroa mites, a major problem for U.S. beekeepers.

The process of breeding queens is complex.

In nature, a typical queen mates in flight with 15 to 20 drones of diverse genetic backgrounds. She then produces offspring. An ideal hive, Cobey said, has about 20 subfamilies – all with the same queen mother, each with a different drone father. Each subfamily of worker bees has its own traits, leading to divisions of labor within the hive.

Artificial breeding tries to replicate aspects of the natural process.

Each year, WSU researchers collect sperm from thousands of drones. The researchers then cryo-preserve the semen in liquid nitrogen at 320.8 degrees below zero Fahrenheit.

A single drone’s semen volume is equal to about one microliter: one-millionth of a liter. Researchers routinely pool the semen of several drones and insert 10 to 12 microliters of semen into a queen.

The process demands precision, said Cobey.

First, Cobey anesthetizes the queen bee, putting her out with brief carbon dioxide treatments.

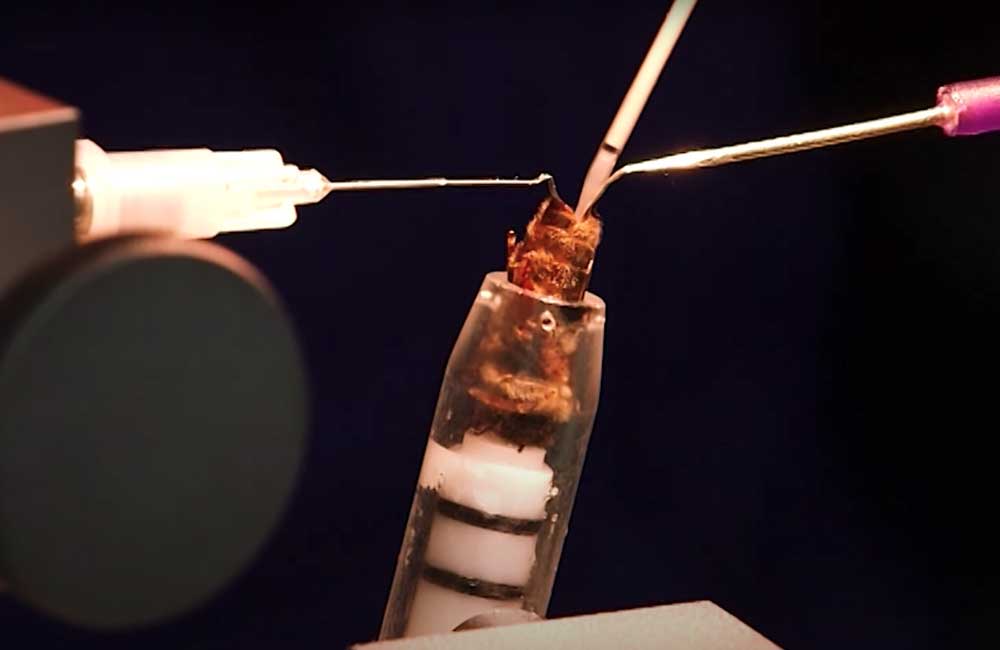

Cobey uses specialized German equipment. She inserts the bee into a queen holder assembly, uses tiny forceps to open the queen’s vaginal chamber and, using a syringe, inserts the semen directly into the median oviduct of the queen.

After insemination, the queen must be carefully introduced into a hive and monitored.

“Once she’s established, she can perform as well as a natural-mated queen,” said Cobey.

Cobey has taught the technique to researchers and beekeepers across the U.S. She estimates between 15 to 20 people are instrumentally inseminating bees professionally, while another 30 to 40 are still learning.

Cobey said she hopes that over time, people doing instrumental insemination will breed better, stronger bees with more genetic diversity.