ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 7:00 am Thursday, November 23, 2023

YAKIMA, Wash. — Lifelong Yakima Valley resident Mike Doty collects fruit crate labels for the thrill of the hunt.

“That’s what it’s all about. Stuff we’ve never seen before,” he said. Thomas Hull, a high school history teacher in Yakima, said collecting “almost becomes an addictive activity.”

A few dozen serious collectors across the Northwest compete and cooperate with each other, scour online for labels, trade, sell and pass along tips.

The tight-knit community is helping preserve an obsolete art form that traced the history of the fruit industry — and the United States — from the late 1880s through the 1950s.

Northwest aficionados generally seek out local apple and pear labels, which emerged in the 1900s.

“So many of the labels are just beautiful,” said Sue Naumes of Medford, Ore., who owns close to 5,000 labels.

“They are really great examples of commercial art and behind the labels is often a story,” said John Baule, Yakima Valley Museum director emeritus and archivist.

Hull sometimes shares those stories in his Davis High School classroom.

During lessons on the Great Depression, he shows labels for Grand Coulee Apples to emphasize the Works Progress Administration’s construction of the Grand Coulee Dam, the water from which irrigates nearly 700,000 acres of farmland in Washington.

“Look at what the New Deal did for agriculture and the American West,” Hull said.

He also shows the K-O Brand Apples label, for Karr Orchards, which features a boxing glove and illustrates labor movement tensions. The artwork references the Battle of Congdon Orchards, a brawl between members of the Industrial Workers of the World, or Wobblies, and growers.

The birth of fruit crate labels is tied to the spread of railroads, the rise of advertising as an economic force, and the dawn of the West as a powerful growing region.

Along the way, labels indicate new art styles, fruit varieties and industrial advancements such as cold storage.

“They capture people, places and moments in time,” said Kelsey Doncaster of Choteau, Mont., a historian and collector with more than 7,000 labels.

The demise of wooden crate labels is linked to lumber supply issues and adoption of cardboard boxes as a cheaper alternative, said Doncaster, who was born and raised in Yakima.

Simplistic labels could be printed or stamped on the cardboard.

By the 1960s and 1970s, the colorful labels had mostly disappeared.

Fruit labels tell more personal stories, too, and collectors often have family ties to agriculture.

Naumes helped manage one of the West’s largest pear companies, Naumes Inc., with its Nanpak label.

Hull’s family owned Hull Ranch and packed fruit under the Diamond H label. “Now I’m on a mission to find those,” he said.

Many orchards, packing houses and cooperatives on vintage labels no longer exist, having been lost to closures, consolidation or development.

Doncaster’s grandfather owned an orchard with apples packed under the Sure Hit label in Omak, Wash. — until two mid-century freezes killed most of his trees.

During the 1980s when fruit prices plummeted, Hull’s family transformed apple acreage into golf links.

Doty’s grandparents worked at the Yakima Fruit Growers Association, and his parents met there while working.

He specializes in the association’s “Big Y” label, which his father glued onto crates as a teen.

Before Doty retired, he worked as a produce buyer throughout Washington, collecting labels on his journeys.

Doty estimated his collection of about 4,000 fruit crate labels is worth upward of $100,000.

He also volunteers to help curate the Yakima Valley Museum’s collection.

The museum started amassing labels in the 1970s. A volunteer realized artifacts from Yakima’s major industry were no longer used commercially, said Baule, author of “The Ultimate Fruit Label Book.”

Now the museum owns 8,000 to 9,000 different labels, mostly local, and 60,000 duplicates — hundreds of which are sold in its gift shop.

The collection is among the largest in the world.

Rooms in the museum basement hold a treasure trove, including stone lithographs for printing, bundles of common labels, and artwork from apple growing regions as far away as Australia.

“Every so often we come across one we’ve never seen before that we want to acquire,” Baule said.

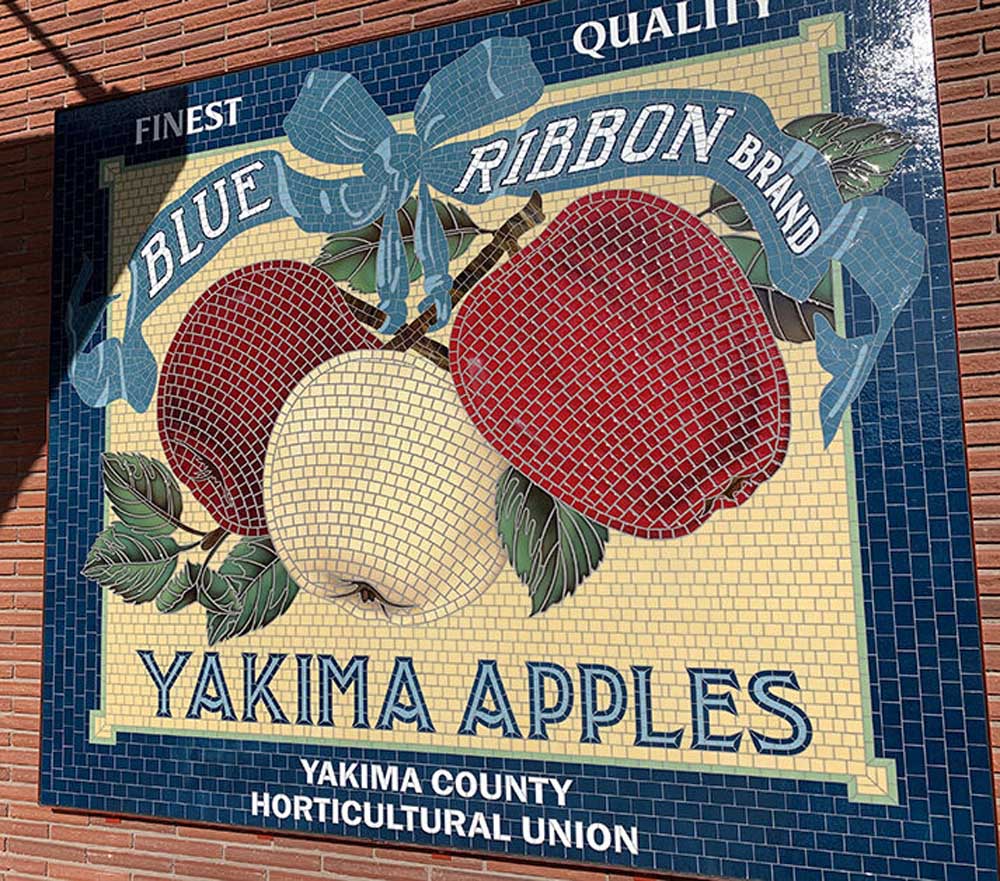

The museum hosts an annual label swap meet the Saturday after Mother’s Day, a recently completed mosaic of a fruit label welcomes visitors, and labels and their histories are featured in exhibits.

In the late 1800s, as rural areas couldn’t consume their increasing ag production, farmers shipped fruits and vegetables farther afield, often by rail.

Crates, which could be tightly packed without damaging the apples, replaced barrels and bushels.

The first fruit labels were stenciled on crates in the 1880s. Farms then went to local newspapers to print paper labels, and then to lithographic companies that sprang up all over the West, said collector and author Pat Jacobsen of Nevada County, Calif.

Fruit crate labels weren’t meant to appeal to consumers, but to wholesale buyers in big cities selling to numerous small grocery stores.

Baule said labels were an idea borrowed from canned food because fruit couldn’t be inspected by buyers.

“They can’t actually taste the apple that’s in the box, so you want to develop a brand labeling,” Baule said.

“The more attractive the label, the more you develop a loyalty to it,” he added.

Labels used an arsenal of strategies to attract the eye and techniques evolved with time.

Before the 1930s, “Everyone wanted a label that was their name, their orchard, their town,” Jacobsen said. Companies started creating more adventurous pictures and brands.

Over time, labels included idyllic landscapes, pin-up girls, wholesome kids, historic characters such as cowboys and Native Americans, and fanciful creatures.

Most labels do their job well, said Carlos Pelley, archivist and librarian for the Yakima Valley Library, which has digitized its label collection.

“Whenever I look at these labels, I start hankering for fresh fruit,” he added.

Pelley has his favorites.

“One of them is Rainier apples, this beautiful picture of Mt. Rainier in the distance, and then a big, juicy Red Delicious sitting right in the middle. Underneath it, it has a bunch of orchard trees,” Pelley said.

The image encapsulates what he saw growing up in the Yakima Valley.

Even in their heyday, fruit labels romanticized the agrarian lifestyle, Naumes said. Today, that’s coupled with a yearning for a simpler time when farmers could thrive on five to 10 acres, she added.

There’s also the uglier side of history such as racist stereotypes.

Hull said the art demonstrates how Americans saw themselves — and others.

Pelley said viewing labels with a modern perspective shows how far the United States has come.

Baule said many labels have slight variations to match fashions of the times, as companies merged or were sold, or for exported fruit.

Stock labels, on which growers printed their name on a generic image, also were widely used.

Labels’ background color changed to note fruit quality, Baule said.

Blue represented the highest quality, “extra fancy.” Red was a step down to “fancy.”

Ironically, the most valuable labels today are those for lower fruit quality, such as green for “C” grade, because fewer were printed.

Labels were made in batches as small as 1,000 or as large as 1 million, Doncaster said.

Scarcity occurred because workers never imagined labels would be collectible. When packing houses adopted cardboard boxes, some burned or threw out labels, or workers used them as scratch paper.

In other instances bundles of labels were stashed away and then surfaced years later.

Common labels can sell for a few dollars apiece, so the hobby can be inexpensive.

Many sought-after labels are worth hundreds of dollars.

The hobby peaked in the early 2000s, however, and prices have since dropped, Doncaster said.

“They’ll continue to drop as the circle of collectors gets smaller and more labels pop up,” he added.

Decades ago, collectors traded through the mail, and the back and forth of letters could take weeks.

The internet has made collecting faster and easier in some ways, but more difficult in others.

Online bidding wars can erupt over coveted labels, leading to prices far above the actual value.

“My wife keeps complaining that I like to win auctions,” Doty said.

Naumes said in the early days of collecting, people only traded. Charging money turned some people away from the hobby.

Still, Northwest aficionados are tame compared to the competitive and crowded world of California citrus label collectors, Naumes said.

Sometimes, Doty isn’t buying single labels but entire collections, in part because hobbyists are dying off.

Doncaster said there are “way less than half” as many collectors as when he started.

A shrinking apple industry due to consolidation means fewer people involved in agriculture, and fewer prime candidates to become collectors.

“There are more people collecting for the images, not because they were in the fruit industry,” Doncaster said.

A few new hobbyists are in their 30s and 40s, including Hull, the teacher. “They’re kind of a breath of fresh air, to know there will be people doing this 30 years from now,” Doty said.

Hull, who’s on the board of the Yakima Valley Museum, said he’ll keep the tradition alive.

“As a historian, I have an opportunity to carry those stories on for another generation,” Hull said.