ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 7:00 am Thursday, April 18, 2024

Environmentalists are back in court in support of the fiction that gray wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountains and Western U.S. are in short supply.

They argue, through their scores of lawyers, that wolves need more protection under the federal Endangered Species Act.

They are wrong.

First, some numbers.

2,797: the number of gray wolves in the Lower 48, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This doesn’t include Alaska, which has 7,000 to 11,000 wolves, according to the state Department of Fish and Game.

And right next door, Canada has 50,000 to 60,000 gray wolves, according to the federal government. Note that a Canadian wolf doesn’t need a passport to take up residence in the U.S.

Clearly, there is no shortage of wolves in the U.S. or Canada.

Second, some facts.

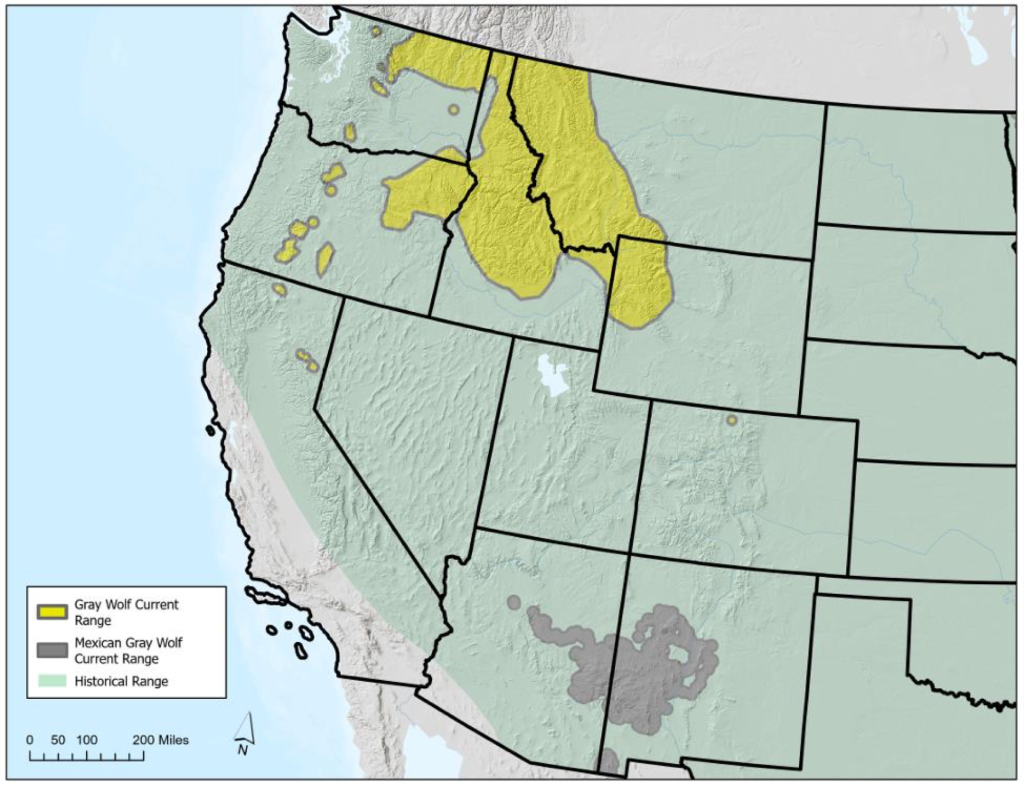

Gray wolves are thriving. Sixty-six were relocated from Canada to Idaho and Yellowstone National Park in the mid-1990s, and others have migrated from Canada to the Lower 48.

As a result, there are now nearly 2,800 wolves in 286 packs in seven states. This rapid spread and growth in numbers counter any argument of a need for protecting wolves. By any measure, wolves have succeeded in reestablishing themselves in the Northern Rocky Mountains and the Western U.S.

Yet the Center for Biological Diversity, Sierra Club, Humane Society of the United States and its affiliate, the Humane Society Legislative Fund, have gone to court seeking protection for the wolves.

This is despite overwhelming evidence that gray wolves continue to thrive in both regions. They eat well, as the continuing attacks on sheep, cattle and game animals show, and they continue to spread.

The lawsuit is the environmental groups’ answer to a determination by the Fish and Wildlife Service that gray wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountains do not warrant relisting under the Endangered Species Act. The agency also found that the gray wolf in the Western U.S. “does not meet the definition of an endangered species or a threatened species.”

Of course that won’t stop the lawsuit, since these groups have made the gray wolf a poster child for preservation. In our opinion, there could be a wolf on every street corner and the environmental groups would be in court somewhere hollering that there aren’t enough.

For the environmental groups, what’s especially concerning is that states are actually managing wolves. Instead of managing them as endangered species and letting their populations grow and spread as fast as possible, managers in some states are limiting their numbers. This will keep their populations — and the populations of other animals on which they prey — healthy.

The Fish and Wildlife Service published its species status assessment for the gray wolf in the Western United States last December. It says that Montana, where wolves were never reintroduced, had a population of 1,087 at the end of 2022. In two other states where they weren’t reintroduced, Washington and Oregon, the populations were 216 and 178, respectively.

In Idaho, where they were reintroduced, the population was 710.

Gray wolves are a success story in the West. They continue to spread into other states without help from the Sierra Club or anyone else.

It’s time for the environmentalists and their lawyers to declare victory and go home. Barring that, they can just go home.

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Featuring quality surplus farm and dairy equipment from farming operations and dealers across Western, WA. Highlights include sellers from Lynden to Snohomish featuring equipment from Farmers Equipment, Inc., Cleave Farms, […]

Bid Now! Bidding Ends March 12, 10 AM MST Dairy, farm, excavation & heavy equipment, transportation, tools, & more! Register Now! Magic Valley Auction www.MVAidaho.com 208-536-5000

Treasure Valley Livestock Auction Caldwell, Idaho Free Delivery within 400 Miles February 25th, 2025 @ 1PM MST VIEW/BID LIVE ON THE INTERNET: LiveAuctions.TV Find us on Facebook at: Idaho […]

The in-person and virtual conference will feature more than 90 speakers, as well as presentations, panel discussions and networking. Organic Seed Alliance (OSA), along with partner Oregon State University’s Center […]

Live Streaming Auction - February 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - February 27, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

Range-Raised • Feedlot-Tested • Carcass-Measured • DNA Evaluated Price Cattle Company with Murdock Cattle Co February 26 Lunch Served At 11:00 AM • Sale Starts 1:00 PM 50 Registered Angus […]

The event features research updates and educational presentations.

Live Streaming Auction - February 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - February 27, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

Moving Back Home! In addition to our yearling bulls, we also added some age-advantage bulls. The sale will take place at the Lewiston Roundup Grounds, just South of Lewiston. Both […]

FRIDAY – February 28, 2025 / 8:30 AM 17129 HIGHWAY 99 NE, WOODBURN, OR 97071 AUCTION DETAILS: Auction Begins: Friday – February 28th, 2025 @ 8:30 AM – (PST) Live-online […]

Trinity Farms BETTER BULLS. BRIGHTER FUTURES. Trinity composite bulls, the perfect solution for advanced beef production. 250 Bulls Available Ellensburg, WA • 3.1.2025 www.trinityfarms.info • (509) 201-0775

Preview: Sat. March 1st 9am - 1 pm Biddings Ends: Thurs. March 6th Starting at 6pm Highlights Include: Bulb planter and harvest equipment, disks, plows, harrows, cultipackers, 4 row planter, […]

Heavy Equipment • Tractors • Construction • Farm Equipment • Vehicles • Trucks • Trailers & More! Virtual Online-Only Auction Full Catalog & Bidding Procedures Available at www.yarbro.com Start […]

Booker's Annual Early Spring Eltopia Auction March 6-7, 2025 www.BookerAuction.com | 509.297.9292

2-Day Online Equipment Auction @ Meridian Equipment Auction CO, Bellingham WA. Now Accepting Quality Machinery Consignments AUCTION INFORMATION Online Only Bidding ONLINE BIDDING OPENS: Feb 22, 2025 DAY 1- Online […]

Oregon State University Surplus hosts Annual Farm Sale Bid on 30+ years of local farm surplus! Join OSU Surplus on March 8th at the Lewis Brown Farm in Corvallis for the […]

Join us for the Genetic Edge Bull Sale! 320 Coming Two-Year-Old Bulls • 265 Yearling Bulls • 305 Calving-Ease Bulls Schedule of Events Friday, March 7, 2025 All Day […]

Online Auction - March 12th Bid Now! Dairy, Farm, Excavation & Heavy Equipment, Transportation, Tools, & More! Magic Valley Auction MVAidaho.com 208-536-5000

March Online Equipment Consignment Auction Online Bidding is Wed, March 12th - Wed, March 19th Chehalis Livestock Market 328 Hamilton Rd. N., Chehalis, WA 98532 Follow Us on Facebook! @Chehalis […]

ONLINE ONLY AUCTION Schritter Farms Retirement Auction Bidding Now Open! Bids Begin Closing on March 12th @ 9AM MST Multiple Locations - Please See Individual Lots For Their Specific Location, […]

Thursday, March 13th at 9:30 AM Rubber Tired Loaders, Crawler Tractors, Cranes, Motor Graders, Haul Trucks, Excavators, Water Trucks, Truck Tractors, Trailers, Attachments and Support Equipment Carlin (Elko), Nevada HIGHLIGHTS: […]

RAM RIDGE LLC & PALM CONSTRUCTION - ONLINE AUCTION Aggregate Crushing & Heavy Equipment Start Date: 10AM | Thursday - March 13 End Date: 10AM | Thursday - March 20 […]

Thursday, March 13th at 9:30 AM ~ Bill Miller Rentals ~ Rubbered Tired Loaders, Crawler Tractors, Cranes, Motor Graders, Haul Trucks, Excavators, Water Trucks, Truck Tractors, Trailers, Attachments and Support […]

March 14th - March 18th 2025 Changes Farm Operations Maxwell, CA Learn more at AUCTION-IS-ACTION.COM Putnam Auctioneers, Inc. CA Bond No. 7238559 Email: putman.kevin@yahoo.com John Putnam - (530) 710-8596 Kevin […]

Saturday, March 15th 9:30 AM Address: 1800 West Bonanza Rd., Las Vegas, NV 89106 Highlights: 2-Tele. Forklifts: Unused JLG 943, Unused JLG 742, 2-Cab & Chassis: (2)Unused Chevy 5500, 3-Detachable […]

March Online Auction Begins to close @3pm MST | March 17, 2025 Early Listings: *2017 Bobcat 418-A-A Mini Excavator, *International 544 Utility Tractor with Loader, *2016 Bobcat E20 Mini Excavator, […]

Multi-Seller - Open Consignment Bidding Now Open - Additional Items Arriving Daily Starts Closing: Tuesday, March 18th @ 2PM (MT) Tractors • Trucks • Trailers • Construction Equipment • Farm […]

Machinery Auction March 19-21 All lots start to close at 8:00 a.m. PST Online Bidding Opens March 14 at 3:00 p.m. PST Items include: Construction Equipment, ATVs, Farm […]

12:30PM Wednesday, March 19, 2025 Performance Tested Bulls: Angus, Simmental and SimAngus, Red Angus, Charolais 90 Day Breeding Guarantee. Western Breeders Assoc. Bonina Feed and Sale Facility, 430 Ferguson Lane, […]

Booker's Annual Early Spring Offsite Farm Auction Ends March 19, 2025 www.BookerAuction.com | 509.297.9292

MAJOR CONSIGNORS: Twin Falls Highway District; KWS Seeds; Molyneux Family Farms; and Sev'rl Area Farmers throughout the Magic Valley NOTICE: Items listing in this auction are located at multiple locations […]

Saturday, March 22, 2025 • At the Ranch • Sandpoint, ID High maternal easy fleshing Cows Low maintenance Heifers High performance Bulls Selling 47 Bulls and 40 Open Heifers […]

Live Streaming Auction - March 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - March 27th, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

FRIDAY – March 28, 2025 / 8:30 AM 17129 HIGHWAY 99 NE, WOODBURN, OR 97071 AUCTION DETAILS: Auction Begins: Friday – March 28th, 2025 @ 8:30 AM – (PST) Live-online […]