ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 8:15 am Monday, June 17, 2024

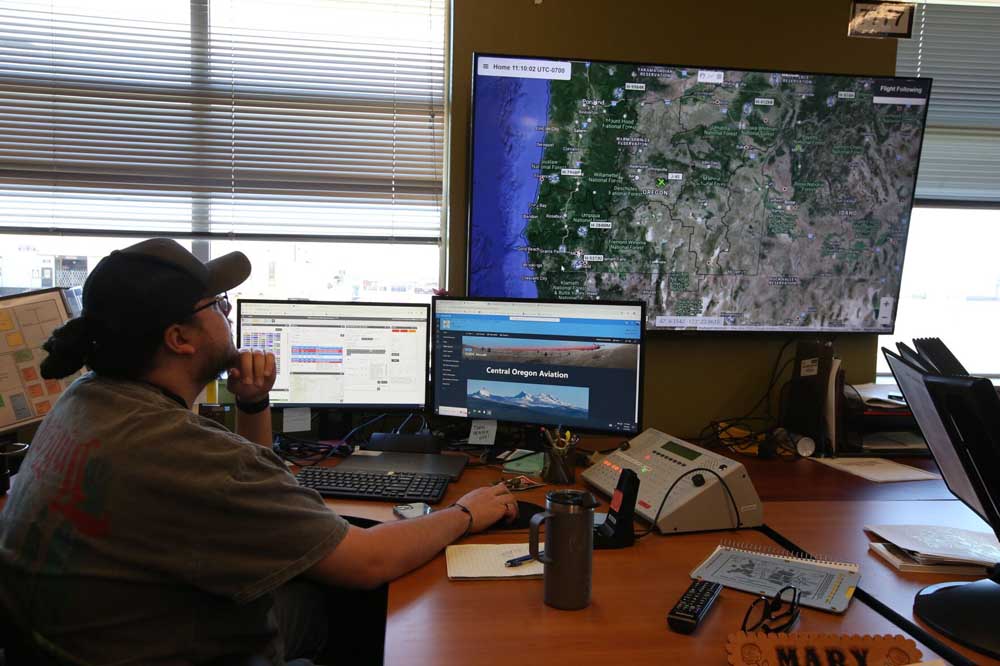

REDMOND, Ore. — There’s a war room on the outskirts of Redmond. Colorful maps stretch from floor to ceiling, each featuring magnets tracking the movement of fire personnel and their equipment. Workers stand behind a wall of computer monitors ready to deploy resources.

But instead of organizing overseas troops, this office in a low-slung building near the Redmond Airport is designed to battle wildfires that erupt in summer across Central Oregon.

The Central Oregon Interagency Dispatch Center serves as a command center to direct the deployment of wildfire crews across the region, one of 19 such centers in the Pacific Northwest. It’s a busy place in summer and designed to protect the homes, infrastructure and the people of Central Oregon.

“It can get a little crazy in here. I call it controlled chaos. With the amount of area we cover we can get a lot of fires at the same time,” said Jada Altman, the manager at the dispatch center.

The dispatch center is part of a vast network of fire stations and offices where firefighters work throughout the year. Their work has become more intense in recent years as climate change, and decades of fire suppression, have created conditions that make wildfires burn hotter and longer than ever before.

The agencies supported by the center manage 4.5 million acres of public and private land across a swath of Central Oregon, stretching from the Gilchrist area all the way north to the Columbia River Gorge. The crest of the Cascades creates its western edge and goes past John Day to the east. The center typically responds to over 300 fires a year.

Altman says action at the center starts to heat up after the Fourth of July and usually goes strong until mid-September or later.

Inside, dispatchers monitor the movement of wildfire crews and aircraft. They use the magnets on their wall map to keep tabs on their location. A magnet tilted on a slant means they are en route to a location. Horizontal means they have arrived. Then the location is recorded on a computer and shared in a database.

“We do this to track our resources, we know where they are at all times so if we do get a fire, we can look at the map and know who are the closest resources and get them rolling as fast as we can,” explains Skylor Bergin, a lead dispatcher.

Bergin says once a crew gets to a resource she’ll get an update from the field and can dispatch more resources if needed.

“Whatever we need we get to them, to the best of our ability,” she said.

Bergin previously worked as a wildland firefighter on Mount Hood so she knows what it’s like to be dispatched to a fire zone. Part of the motivation to do her current job stems from her past work in the field.

“I came from fire. I know what it’s like to get that fire call. I know how exciting it is,” she said.

Across the hall in the detection camera room, Oregon Department Forestry wildland firefighter dispatcher Matt Noble monitors 12 mountaintop cameras, looking for smoke, sort of like a modern day fire lookout. Most are located on existing communication towers of various types including cell and radio towers.

Noble plots the location of new fire starts on mapping software and transmits the GPS location so the dispatcher can order a resource to inspect the smoke source. Each year he locates around 150 fire starts. Ten to 12 Forest Service employees still watch for fires in the field as they have done for decades, he said.

Back in the main room, fire officials explain that resources are dispatched on a priority basis. So when things get busy, calls need to be made as to which crews get resources. Aircraft are the most in-demand resource.

Currently, that responsibility falls on Eric Miller, acting fire staff officer for the Central Oregon Fire Management Service. He has been fighting fire since 1994 and spent 20 years supervising hot shot crews so he knows his way around a fire as much as the dispatch center.

“We make the tough decision sometimes on who gets resources right now and who might get them tomorrow,” said Miller. “When it comes to making a hard call or who gets that air tanker, ultimately that decision will come to the duty officer.”

When fires start to ramp up there could be up to 40 people in the room lending support to crews in the field. Altman says maintaining a calm voice, to avoid agitating crews in the field is critical on busy days.

“We plot each fire in our (computer aided dispatch) system, we figure out land ownership, and we get eyes on it on their air in on the ground,” she said.

On busy days in late summer, the dispatch center may be monitoring around 10 fires a day but those numbers can soar after a large lightning storm — the center confirmed 76 lighting fires on a single day in August 2022.

Once crews are dispatched and a moment of calm arrives, the dispatchers can take a breather outside, said Bergin. Altman’s stress relief comes on weekends when she works in her home garden. But her plants are never too far away, rows of Baquinho pepper starts and other vegetable plants in tiny plastic cells are occasionally spotted in her office.

Altman has also worked on hand crews and different desks within the dispatch. Her father was a fire management officer so she grew up understanding the importance and challenges of this career. She started at age 16 as a member of the Forest Service’s Youth Conservation Corps.

She said that working on the initial attack desk and aircraft dispatch is the most stressful, but through it all she has plugged away and advanced through the ranks of the interagency dispatch center.

“I like being a support for the firefighters on the ground,” said Altman. “I like being their lifeline and their support. So, whatever they need, it’s our job to find it and get it for them.”