ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 2:08 pm Friday, February 21, 2025

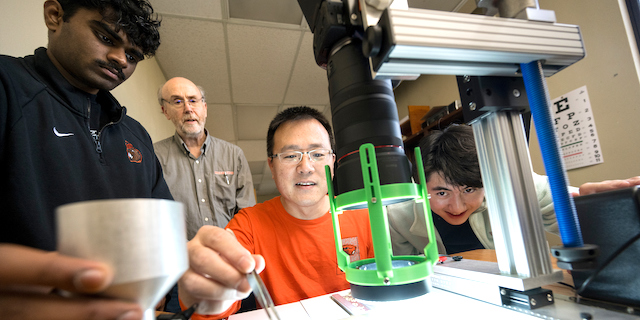

For the grass seed industry, spotting weed seeds and other unwanted interlopers among thousands of grass seeds is as tedious as it is necessary.

Samples of grass seed are repeatedly analyzed by growers to avoid penalties for weed seeds and other impurities, while seed companies must do the same to comply with labeling rules.

“That takes away time from the rest of their work,” said Dan Curry, director of seed services at Oregon State University. “They don’t want any weeds or any other crops in there.”

By delegating the mind-numbing task to computers, Oregon State University scientists plan to save countless hours of labor without sacrificing seed purity.

Optical tools don’t grow weary as quickly as human eyes, while artificial intelligence software isn’t as prone to wandering thoughts as the human brain.

An interdisciplinary team at OSU is combining those technologies, betting they’ll prove adept at identifying weed seeds and other contaminants in samples of grass seed.

The university’s “Computer Seed I.D.” project also aims to spare seed cleaners and other companies from frequently teaching new employees to discern among seed types.

“The problem is people change within a company or leave the company, and all that training and experience is now leaving,” Curry said.

Examining seed samples is a crucial duty at seed warehouses, which are often owned by farmers who run the crop through filters and other seed cleaning equipment to meet buyer specifications.

If too many contaminants are left in the final product, growers get docked pay, but the removal process risks losing desirable seeds and thus yields and revenues.

Inspecting seed samples helps farmers balance those competing concerns and is a critical job each harvest season.

Unfortunately, the process requires evaluating tens of thousands of grass seeds, which soon tires people out and can lead to mistakes.

“That can be very challenging and tough,” said Yanming Di, an OSU statistician working on the project. “There are particular challenges with grass seed, one of them being that they’re really, really tiny.”

The idea of having the chore taken over by machines came about nearly a decade ago, but the project was officially started in mid-2023 with $255,000 in grants from USDA, OSU’s College of Agriculture, and Oregon crop commissions representing ryegrass, tall fescue and fine fescue producers.

The project team is comprised of 11 professors and students specializing in seed crops, statistics, computer science, precision agriculture, business, biology, robotics and mechanical engineering. They are designing two systems: a smaller portable “light box” that connects to a smartphone app meant for farmers, and a larger device with a higher-resolution camera meant for seed labs.

Using scores of sample images, an artificial intelligence program has been trained to differentiate between ryegrass seeds, tall fescue seeds, and the seeds of curly dock, a common weed.

Eventually, the team expects to calibrate the system to identify each type of seed that it may encounter in samples.

The program’s ability to distinguish between two types of desirable grass seed is promising for the project’s future, said Di. “That’s challenging even for human analysts.”

It’s not yet clear how each system will be sold or otherwise made available to farmers and seed labs. It will probably be another year and a half before the systems are ready to be officially shared with the grass seed industry, as the team is still making improvements.

For images to be recognizable to the artificial intelligence program, the seeds must currently be evenly distributed by hand and the photo background must be removed on a computer, but the team intends to automate these tasks to minimize human intervention.

Another possibility is the development of a conveyor system that mechanically or robotically separates out questionable seeds. That way, human analysts can focus on identifying the weeds or other contaminants rather than hunting for them amid a mass of desirable seeds.

“We still need the seed analysts. It would make their work more efficient,” Curry said.

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Featuring quality surplus farm and dairy equipment from farming operations and dealers across Western, WA. Highlights include sellers from Lynden to Snohomish featuring equipment from Farmers Equipment, Inc., Cleave Farms, […]

Bid Now! Bidding Ends March 12, 10 AM MST Dairy, farm, excavation & heavy equipment, transportation, tools, & more! Register Now! Magic Valley Auction www.MVAidaho.com 208-536-5000

Treasure Valley Livestock Auction Caldwell, Idaho Free Delivery within 400 Miles February 25th, 2025 @ 1PM MST VIEW/BID LIVE ON THE INTERNET: LiveAuctions.TV Find us on Facebook at: Idaho […]

The in-person and virtual conference will feature more than 90 speakers, as well as presentations, panel discussions and networking. Organic Seed Alliance (OSA), along with partner Oregon State University’s Center […]

Live Streaming Auction - February 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - February 27, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

Range-Raised • Feedlot-Tested • Carcass-Measured • DNA Evaluated Price Cattle Company with Murdock Cattle Co February 26 Lunch Served At 11:00 AM • Sale Starts 1:00 PM 50 Registered Angus […]

The event features research updates and educational presentations.

Live Streaming Auction - February 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - February 27, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

Moving Back Home! In addition to our yearling bulls, we also added some age-advantage bulls. The sale will take place at the Lewiston Roundup Grounds, just South of Lewiston. Both […]

FRIDAY – February 28, 2025 / 8:30 AM 17129 HIGHWAY 99 NE, WOODBURN, OR 97071 AUCTION DETAILS: Auction Begins: Friday – February 28th, 2025 @ 8:30 AM – (PST) Live-online […]

Trinity Farms BETTER BULLS. BRIGHTER FUTURES. Trinity composite bulls, the perfect solution for advanced beef production. 250 Bulls Available Ellensburg, WA • 3.1.2025 www.trinityfarms.info • (509) 201-0775

Preview: Sat. March 1st 9am - 1 pm Biddings Ends: Thurs. March 6th Starting at 6pm Highlights Include: Bulb planter and harvest equipment, disks, plows, harrows, cultipackers, 4 row planter, […]

Heavy Equipment • Tractors • Construction • Farm Equipment • Vehicles • Trucks • Trailers & More! Virtual Online-Only Auction Full Catalog & Bidding Procedures Available at www.yarbro.com Start […]

Booker's Annual Early Spring Eltopia Auction March 6-7, 2025 www.BookerAuction.com | 509.297.9292

2-Day Online Equipment Auction @ Meridian Equipment Auction CO, Bellingham WA. Now Accepting Quality Machinery Consignments AUCTION INFORMATION Online Only Bidding ONLINE BIDDING OPENS: Feb 22, 2025 DAY 1- Online […]

Oregon State University Surplus hosts Annual Farm Sale Bid on 30+ years of local farm surplus! Join OSU Surplus on March 8th at the Lewis Brown Farm in Corvallis for the […]

Join us for the Genetic Edge Bull Sale! 320 Coming Two-Year-Old Bulls • 265 Yearling Bulls • 305 Calving-Ease Bulls Schedule of Events Friday, March 7, 2025 All Day […]

March Online Equipment Consignment Auction Online Bidding is Wed, March 12th - Wed, March 19th Chehalis Livestock Market 328 Hamilton Rd. N., Chehalis, WA 98532 Follow Us on Facebook! @Chehalis […]

Online Auction - March 12th Bid Now! Dairy, Farm, Excavation & Heavy Equipment, Transportation, Tools, & More! Magic Valley Auction MVAidaho.com 208-536-5000

Bidding starts on Wednesday, March 12th Go to www.clmauctions.com and click on Hibid link to view and bid on over 1,000 lots! Lots of great pickups, trailers, tractors, cars, farm trucks, haying […]

ONLINE ONLY AUCTION Schritter Farms Retirement Auction Bidding Now Open! Bids Begin Closing on March 12th @ 9AM MST Multiple Locations - Please See Individual Lots For Their Specific Location, […]

Thursday, March 13th at 9:30 AM ~ Bill Miller Rentals ~ Rubbered Tired Loaders, Crawler Tractors, Cranes, Motor Graders, Haul Trucks, Excavators, Water Trucks, Truck Tractors, Trailers, Attachments and Support […]

RAM RIDGE LLC & PALM CONSTRUCTION - ONLINE AUCTION Aggregate Crushing & Heavy Equipment Start Date: 10AM | Thursday - March 13 End Date: 10AM | Thursday - March 20 […]

Thursday, March 13th at 9:30 AM Rubber Tired Loaders, Crawler Tractors, Cranes, Motor Graders, Haul Trucks, Excavators, Water Trucks, Truck Tractors, Trailers, Attachments and Support Equipment Carlin (Elko), Nevada HIGHLIGHTS: […]

March 14th - March 18th 2025 Changes Farm Operations Maxwell, CA Learn more at AUCTION-IS-ACTION.COM Putnam Auctioneers, Inc. CA Bond No. 7238559 Email: putman.kevin@yahoo.com John Putnam - (530) 710-8596 Kevin […]

Saturday, March 15th 9:30 AM Address: 1800 West Bonanza Rd., Las Vegas, NV 89106 Highlights: 2-Tele. Forklifts: Unused JLG 943, Unused JLG 742, 2-Cab & Chassis: (2)Unused Chevy 5500, 3-Detachable […]

March Online Auction Begins to close @3pm MST | March 17, 2025 Early Listings: *2017 Bobcat 418-A-A Mini Excavator, *International 544 Utility Tractor with Loader, *2016 Bobcat E20 Mini Excavator, […]

Multi-Seller - Open Consignment Bidding Now Open - Additional Items Arriving Daily Starts Closing: Tuesday, March 18th @ 2PM (MT) Tractors • Trucks • Trailers • Construction Equipment • Farm […]

Machinery Auction March 19 & 20 All lots start to close at 8:00 a.m. PST Online Bidding Opens March 14 at 3:00 p.m. PST Items include: Construction Equipment, […]

12:30PM Wednesday, March 19, 2025 Performance Tested Bulls: Angus, Simmental and SimAngus, Red Angus, Charolais 90 Day Breeding Guarantee. Western Breeders Assoc. Bonina Feed and Sale Facility, 430 Ferguson Lane, […]

Booker's Annual Early Spring Offsite Farm Auction Ends March 19, 2025 www.BookerAuction.com | 509.297.9292

MAJOR CONSIGNORS: Twin Falls Highway District; KWS Seeds; Molyneux Family Farms; and Sev'rl Area Farmers throughout the Magic Valley NOTICE: Items listing in this auction are located at multiple locations […]

Saturday, March 22, 2025 1:00pm PT • At the Ranch • Sandpoint, ID High maternal easy fleshing Cows Low maintenance Heifers High performance Bulls Selling 47 Bulls and 40 […]

Discover the Estate of Afton Jacobson, offering 743± acres of farmland just 4 miles south of Pullman, WA. This expansive property features 6 parcels, two including residences and outbuildings, providing […]

Live Streaming Auction - March 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - March 27th, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

March 28th, 9:00 am - 5:00 pm March 29th, 9:00 am - 3 pm The 4th Annual Central Oregon Agricultural Show presents the best of the region’s agricultural industry. The […]

FRIDAY – March 28, 2025 / 8:30 AM 17129 HIGHWAY 99 NE, WOODBURN, OR 97071 AUCTION DETAILS: Auction Begins: Friday – March 28th, 2025 @ 8:30 AM – (PST) Live-online […]

Bids Open at 3pm PST on March 20th Start Closing at 8am PST, April 2 & 3, 2025 On-Site Preview available Monday to Saturday from 9am to 4pm Visit www.I-5auctions.com […]

Thursday, April 3, 2025 - Brigham City, Utah Live & Online Bidding (16) Tractors - Wheel loaders - Skid Steers - (8) Semis, Trucks w/Laird Feed Box, Ross Beds - […]

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Go to bakerauction.com for more information. Auction Soft Closes: Thurs., April 3rd 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Consignment Item Receiving: March 17th - March 31st, […]