ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 8:30 am Tuesday, February 11, 2020

BURLEY, Idaho—America’s original prairies were once vibrant with flowers, forbs and grasses, supporting the health of the soil beneath. But in the conversion to agricultural land, they lost the diversity that promoted productivity and protected against pests and disease.

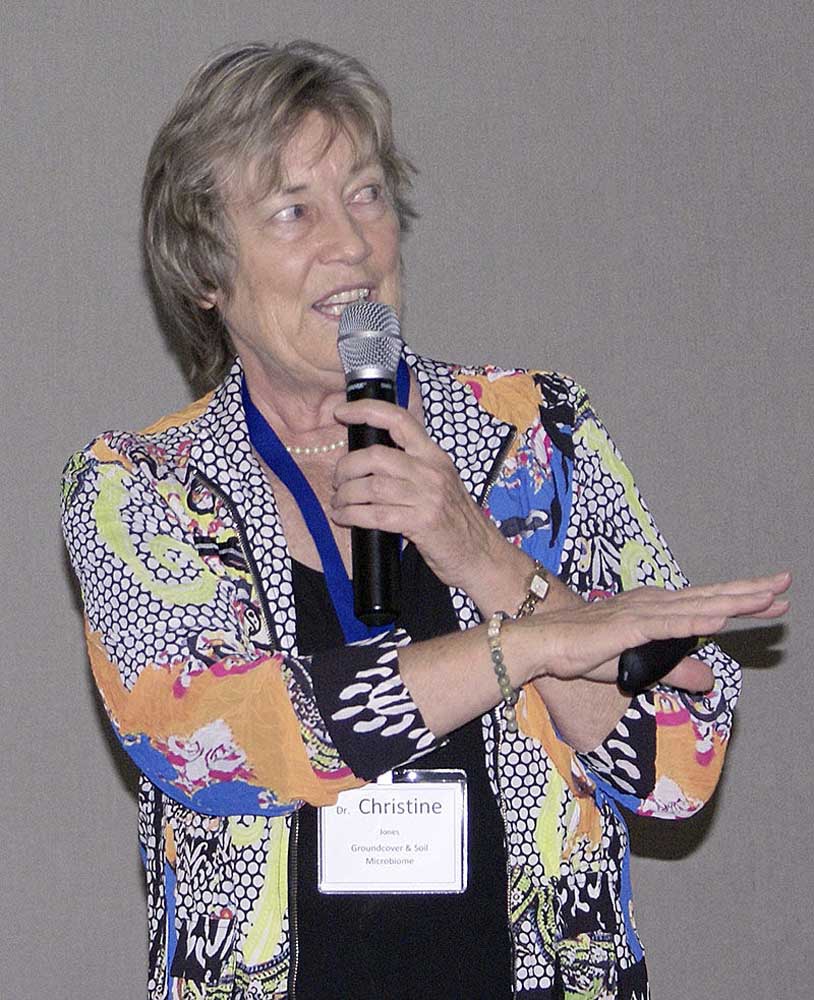

The trouble is agricultural landscapes have become so simplified people aren’t even aware of how incredibly productive more diverse systems can be, Christine Jones, a soil ecologist, told those attending the East Cassia and West Cassia soil conservation districts’ 6th Annual Soil Health Workshop.

Plant diversity holds extraordinary power for regenerative agriculture, she said.

Different plants have different root architectures that support a microbial network in soil. They all support each other, rather than compete, to make each species more productive, she said.

“Diverse plant communities support a diverse soil microbiome,” she said.

It’s a symbiotic relationship, as a diverse microbiome supports the host plants, she said.

Research all over the world has shown the benefits of multi-species cropping compared with monoculture, she said.

In 2006, the Burleigh County, N.D., Soil Conservation District performed an experiment planting several different cover crops each as a monoculture and planting them all together as a polyculture. It turned out to be a drought year, and all the monocultures failed.

But there was no sign of drought stress in the polyculture, she said.

In that setting, plant diversity created a common microbial network and energized the soil. The plants were able to get water and nutrients from a long way away, she said.

In a 2015 trial in Alberta, Canada, researchers planted a triticale monoculture next to triticale oversowed with a multi-species mix. The monoculture failed, whereas the polyculture showed no sign of water stress.

The same thing happened in a more recent trial in Oklahoma with a sorghum monoculture and sorghum polyculture, she said.

Drought tolerance is one of the main benefits of plant diversity. In fact, she thinks what would be considered drought years in monoculture agriculture would just be considered dry years in a polyculture setting, she said.

Another (long-term) experiment in Jena, Germany, showed high diversity produced greater plant yield than nitrogen in monoculture or low diversity plantings, she said.

The research found the more and different kinds of plants resulted in more biomass and increased soil carbon. The most important factor for plants is soil carbon, and you can only build soil carbon with living plants. Soil carbon declines with monocultures, she said.

The research also found that plants in the polyculture were more tolerant to both drought and waterlogging due to improved soil structure, she said.

Another less formal case was a dairy farmer in New Zealand who replaced 5 acres of his ryegrass and clover pasture with a multi-species mix, which included many flowering species. The land is comprised of pumice soil with only a couple of inches of dark topsoil.

The switch to multi-species plants resulted in building several inches of topsoil and increased milk production in the cows, she said.

Diverse plant communities not only improve soil health and plant productivity but also increase the nutrients in food and feed, she said.