ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 9:30 am Friday, June 14, 2024

More than 750 people sent letters last spring to the U.S. Forest Service with comments about the agency’s multiyear effort to write new long-term management plans for the three national forests in the Blue Mountains, and almost 600 people attended public meetings across the region.

Letter writers commented on a variety of topics, including motor vehicle access, areas potentially eligible to be designated by Congress as wilderness, wildfire threats, how logging, grazing and mining will be managed, the effects of climate change, and protecting wildlife habitat.

Opinions varied widely, and on several topics, such as wilderness and logging, some commenters’ preferences were in effect opposite from those submitted by others.

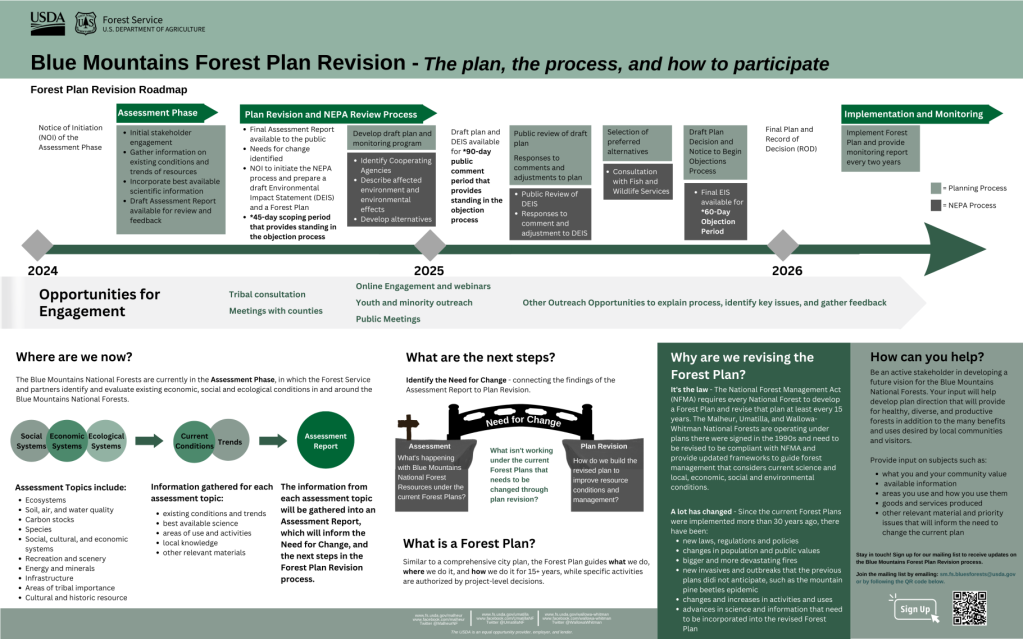

The Forest Service is in the second of 10 steps to revise the management plans for the Wallowa-Whitman, Umatilla and Malheur national forests. The forests, which encompass about 5.5 million acres — an area bigger than Rhode Island and Delaware combined — have been operating under management plans adopted in 1990.

Typically such plans are revised every 15 years or so.

The current timeline, although subject to change, calls for the new plans to be approved in 2026.

Michael Neuenschwander, who is leading the revision team for the Forest Service, said, “The diversity of voices across the Blues was represented in the feedback the revision team received. We heard a wide spectrum of public opinion, from those concerned with the preservation of natural resources to those interested in wide open access across the forests.”

Shaun McKinney, supervisor of the Wallowa-Whitman, said he was “impressed by the volume and incredible level of detail of the public feedback we received. The communities across the Blues value their public lands and hold local knowledge that the Forest Service will incorporate in the draft assessment. Public opinion is an integral part this process. Using the 2012 planning rule, the Forest Service will be engaging with the public every step of the way. We need public participation for the Forest Plan Revision to succeed.”

Management plans list the general goals for each forest but do not describe or authorize specific projects, such as timber sales or recreation improvements. Site-specific projects are analyzed separately through the federal National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires that the agency give the public a chance to comment before making a decision.

The second step in the revision process is the assessment phase, and is designed to gather information about conditions and trends on the forests, and potential problems with managing the forests that could be addressed in the new plans.

The Forest Service released a draft assessment in March 2024, then scheduled a series of eight public meetings in April across the region that attracted almost 600 people.

Forest Service officials will use the letters, comments from the public meetings and other input to craft the final assessment, which is slated to be released this fall.

The agency will also notify the public that it will write an environmental impact statement studying the potential effects of a range of strategies for managing the three forests.

A draft of that study, and a draft of the forest plans, are slated to be released to the public for comment in early 2025, with a final version released later in the year, also subject to public comment.

“Our schedule for the next phases of this forest plan revision process is inherently dynamic,” Neuenschwander said. “We aim to incorporate the public feedback received on the draft assessment over the summer months. We will also be working to build plan components and hope to be reaching back out to the public in the fall. A formal public comment period will occur for the scoping phase of the (draft environmental impact statement).”

The Forest Service initially started work on new plans for the three national forests in the Blue Mountains in 2003, but two subsequent efforts stalled.

The agency was already almost a decade behind the usual schedule when it released a draft version of new plans for the forests in 2014.

But after hearing complaints, some from people who thought the plans were too restrictive on logging, grazing and other uses, and some from people who thought the plans weren’t restrictive enough, Forest Service officials withdrew the draft plans.

The agency tried again in 2018, releasing a final environmental impact statement analyzing the proposed new plans.

That, too, prompted a raft of objections.

The Eastern Oregon Counties Association, which includes Baker, Grant, Union, Wallowa, Umatilla and Morrow counties, listed eight main objections: economics, access, pace and scale of restoration, grazing, fire, salvage logging, coordination among agencies and wildlife.

The Forest Service withdrew that proposal as well in March 2019.

Chris French, deputy chief for the Forest Service, stated the proposed plan was difficult to understand and “(did) not fully account for the unique social and economic needs of local communities in the area.”

In 2023 the Forest Service restarted the process again.

Following is a list of some of the common topics that commenters mentioned in their letters, and excerpts from several letters.

Almost 1 million acres in the Blue Mountains forests are wilderness now, including Oregon’s biggest, the 350,000-acre Eagle Cap Wilderness in the Wallowa Mountains, part of the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest.

Although only Congress can designate federal wilderness — within which motorized vehicles are prohibited, as well as bicycles — the draft assessment included a map that showed areas that might have wilderness characteristics and could potentially be suitable for wilderness designation.

The Forest Service has not recommended any of those areas as wilderness. No new wilderness has been designated in the Blue Mountains since the current forest plans were adopted in 1990.

Some commenters, though, contend that areas shown on the map as potentially being suitable for wilderness should not even be considered.

Christina Witham, a Baker County commissioner, addressed the issue in her comments.

Witham cited, among other areas on the map, a large swath of the Elkhorn Mountains west and northwest of Baker City shown as potential wilderness.

“The large polygon encompassing the Elkhorn Mountain Range, running northwest from Baker City, is not potential wilderness due to our watershed (Baker City’s) and the lack of management to protect it,” Witham wrote in a letter. “Because of the history of and current mining activities, numerous roads leads to trailheads, such as the very popular Elkhorn Crest Trail, this should not be considered.”

Witham also argued in her letter that lands adjacent to the Eagle Cap Wilderness, on the south and west sides of the Wallowas, should not be considered as potential wilderness “due to the history of and current mining activities, numerous roads leading to trailheads such as the very popular Boulder Park area. There is ample wilderness on the north face of the Eagle Cap Mountain Range, already in place and no new wilderness needed.”

Mark Barber, secretary/treasurer of the Eastern Oregon All Terrain Vehicle Association, also wrote that he doesn’t believe the Forest Service should designate more wilderness in the Blue Mountains.

“We have concerns about additional designated wilderness on the forests,” Barber wrote. “We see no areas that fit the original definition or intent of wilderness. Some of the current wilderness is marginal at best when it comes to the original reasons for preserving those lands and we see no reason to add more to the forests.”

Doni Bruland, Baker County’s natural resources coordinator, wrote in her comments that the county’s 2016 natural resources plan “states very plainly that the County will not support any additional set-asides, including, but not limited to, Wilderness, Study, or Areas of Environmental Concern. In addition, there is to be “no net loss of roads or access,” something that set-asides would greatly impact.”

Nora Aspy, of Halfway, wrote that “Declaring any portion of the Wallowa Whitman surrounding Pine Valley and Halfway wilderness, will detrimentally affect this city and community economically, recreationally, and mentally. Please reconsider establishing these areas of wilderness; as they are not wilderness. Rather this is our backcountry and backyard.”

But other commenters endorsed designating more wilderness areas.

Susan Bolgiano urged Forest Service officials to write new management plans that “contain strong clear standards of protection,” including recommending new wilderness areas.

“In this age of climate change and an extinction crisis, few regions in the lower 48 are more deserving of strong protections than the forests of the Blue Mountains,” Bolgiano wrote. “Natural processes and “messy forests” do not threaten these landscapes. The real threat is a return to industrial logging, further fragmentation, overgrazing, climate change, manipulation, continued fire suppression, and increased development.”

Jared Kennedy, organizational consultant for the Greater Hells Canyon Council, suggested in his comment letter that the Forest Service consider protecting “intact unroaded landscapes over a thousand acres” for wilderness designation or other protection.

“Rather than focus on more logging, backcountry thinning, grazing, and motorized use of our forests, investments should be made in traditional quiet recreation, non-commercial thinning near homes and communities, carbon sequestration and storage, fire use, road reductions, first foods, stream restoration, wildlife recovery, enforcement of laws, and the restoration of natural processes,” Kennedy wrote.

Doug Heiken, who submitted comments on behalf of Oregon Wild, a conservation group, wrote that “wilderness is just one among many reasons to protect unroaded areas. The FS needs to recognize that unroaded areas provide disproportionate public values such as clean water, biodiversity, carbon storage, resilience to climate change, recreation, and scenery.”

Barber, from the Eastern Oregon All Terrain Vehicle Association, urged forest officials to maintain the current level of motor vehicle access to the Wallowa-Whitman and Malheur national forests.

Those two forests do not yet have travel management plans, in which the Forest Service designates which roads and trails are open to motor vehicles, with the remainder being closed.

The Umatilla already has such a system in place.

Forest Service officials have said they will not start the travel management plan process for the Wallowa-Whitman and Malheur until the new forest plans have been adopted.

Barber wrote in his letter that “open access to the Wallowa-Whitman and Malheur National Forests is vital in supporting local economies and communities. The assessment fails to consider the value of this open access and ensure that it is preserved for future generations. Keeping the Wallowa-Whitman and Malheur National Forests as open unless designated closed for motorized access should be maintained. We have seen no valid reasons for a change to this policy.”

Fuji and Jim Krieder, who live in La Grande, own forested property in the Blue Mountains and described themselves in their letter as “recreationalists, backpackers, hikers, rafters, photographers, birders, and all around local residents who love our forests and public lands,” urged forest officials to protect mature and old growth trees because they “do an exponentially greater job at capturing carbon, an issue that the Plan must also emphasize more. You cannot have too many old growth trees.”

Regna Merritt, of Portland, also cited old growth trees in her letter.

“In the next phase of forest planning, please draft plans that include strong protections for mature and old growth trees, wildlife habitat connectivity, riparian areas, and roadless landscape,” Merritt wrote. “New forest plans must incorporate clear, enforceable standards to protect mature and old trees of all species.”

Kevin Martin, of Pendleton, president of the Blue Mountain chapter of the Oregon Hunters Association, addressed in his comments the issue of elk congregating on private property, where they can damage crops and where they are in some cases not accessible to hunters.

Martin calls on the Forest Service in the plan revision to try to boost the amount of forage for elk on the national forests “through thinning and prescribed burning,” and to reduce the density of roads open to motor vehicles “to improve elk security.”

Those steps could help encourage elk to move onto national forest land, Martin wrote.

A Forest Service website includes all of the more than 750 comments the agency received this spring about the forest plan revision process, as well as maps, timelines and other information.

Go to the Umatilla National Forest’s website, www.fs.usda.gov/umatilla. Then click on “Blue Mountains Forest Plan Revision” under the Quick Links at the right side of the page.

“The diversity of voices across the Blues was represented in the feedback the revision team received. We heard a wide spectrum of public opinion, from those concerned with the preservation of natural resources to those interested in wide open access across the forests.”

— Michael Neuenschwander, project leader, Blue Mountains Forest Plan revision team