ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 1:20 am Tuesday, December 10, 2013

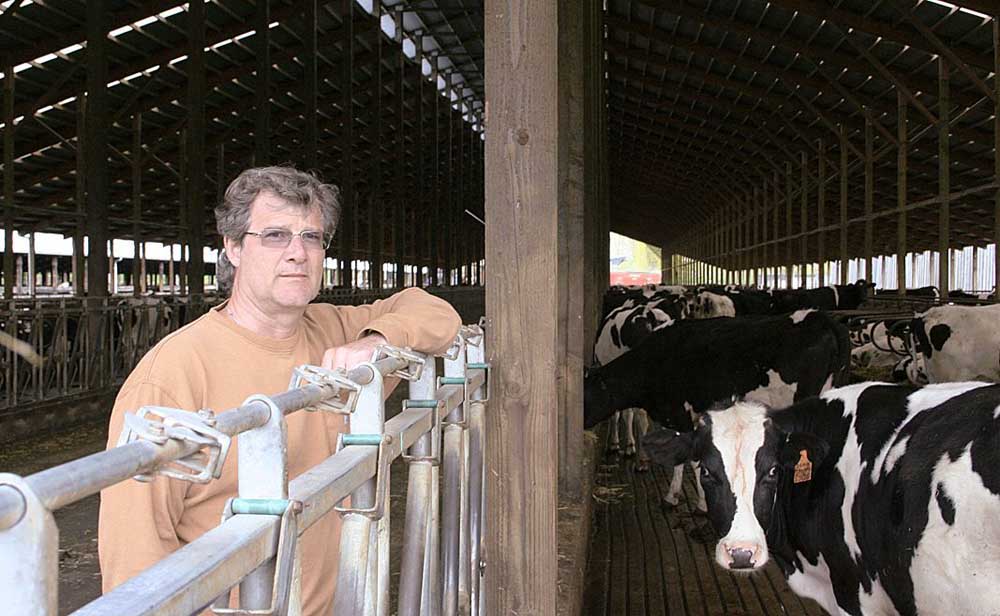

Roughly four years ago, dairy farmer Louie Kazemeir stopped using a synthetic hormone that boosts milk production.

If he wanted to continue using recombinant bovine somatotropin, or rBST, Kazemeir would have to pay “astronomical trucking charges” to ship the milk to a segregated location, he said.

“I’m not willing to pay the extra fee,” said Kazemeir, who farms near Rickreall, Ore.

The popularity of rBST has fallen sharply among dairy farmers across the U.S., according to an economic study.

More than two-thirds of dairy farmers who have ever treated their cows with rBST have stopped using it, the study found.

“It was heralded as a savior and panacea for the dairy industry, but it didn’t really turn out that way,” said Henry An, the study’s author and an economics professor at the University of Alberta.

Despite being approved by the Food and Drug Administration, critics of rBST claimed its use was harmful to cows treated with the hormone and potentially dangerous to human milk consumers.

Many farmers have likely stopped using rBST due to the backlash against the product from some consumers and because it often doesn’t measurably improve profits, said An, who considers himself an “agnostic” regarding the product’s alleged dangers and virtues.

The steepest drop in rBST usage has been among larger dairies like Kazemeir’s, which raise more than 1,000 cattle. In 2005, about 44 percent of such operations used the hormone, compared to 16 percent in 2010, according to the study, which relied on USDA survey data.

Across all U.S. dairies, the prevalence of rBST usage has declined from about 17 percent to less than 10 percent in that time, the study said.

That’s far below projections prior to the hormone’s approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1994, when some economists estimated that between 63 percent and 98 percent of dairymen would adopt the technology, the study said.

While the public controversy over rBST likely discouraged adoption, economic studies have consistently been unable to correlate its usage with higher profits, said An.

The hormone was initially intended to improve the efficiency of dairy production by inducing cows to generate more milk per unit of feed, he said.

However, hitting that “sweet spot” of milk production requires careful monitoring of cow feed consumption, An said. “It’s just not feasible for most producers.”

For many dairies, rBST simply boosted milk output but didn’t put more money into the farmers’ pocket because cows were consuming more feed, he said.

“There seems to be this fixation — how much milk you’re putting out, when you should be concentrating on how much money you’re making,” An said.

Since some dairies are continuing to use rBST, it suggests that they’re able to perfect its usage enough to increase profits, he said.

On average, though, the product hasn’t been associated with better margins, An said.

The lack of a strong economic incentive to treat cows with rBST was likely a deciding factor in many dairy farmers’ discontinuation of the technology, he said.

For retailers, milk is often a “loss leader” that’s intended to get consumers in the door, An said.

When a vocal group of opponents protested rBST usage, some retailers figured they weren’t making money on milk anyway and so it wasn’t hard for them to reject milk from rBST-treated cows, he said.

“It’s a good candidate to make a token gesture, if you will,” An said.

The retailer response prompted some major dairy cooperatives to pay farmers less for milk from rBST-treated cows, due to the segregation costs involved, he said.

“That was one of the last straws for people,” An said. “If you’re not making much money to begin with, then you get docked, what’s the point?”

Capital Press was unable to reach Elanco, which manufactures rBST and sells it under the Posilac brand name, for comment.

Cow health problems also likely contributed to the dropping popularity of rBST, said Rick North, a longtime opponent of the hormone and the retired director of the Campaign for Safe Food, a subsidiary of the Physicians for Social Responsibility non-profit.

The hormone causes increase mastitis, or inflammation of the udders, which forces dairies to remove cows from production and spend more money on antibiotics, he said. “It just burns these cows out.”

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Featuring quality surplus farm and dairy equipment from farming operations and dealers across Western, WA. Highlights include sellers from Lynden to Snohomish featuring equipment from Farmers Equipment, Inc., Cleave Farms, […]

Bid Now! Bidding Ends March 12, 10 AM MST Dairy, farm, excavation & heavy equipment, transportation, tools, & more! Register Now! Magic Valley Auction www.MVAidaho.com 208-536-5000

Treasure Valley Livestock Auction Caldwell, Idaho Free Delivery within 400 Miles February 25th, 2025 @ 1PM MST VIEW/BID LIVE ON THE INTERNET: LiveAuctions.TV Find us on Facebook at: Idaho […]

The in-person and virtual conference will feature more than 90 speakers, as well as presentations, panel discussions and networking. Organic Seed Alliance (OSA), along with partner Oregon State University’s Center […]

Live Streaming Auction - February 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - February 27, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

Range-Raised • Feedlot-Tested • Carcass-Measured • DNA Evaluated Price Cattle Company with Murdock Cattle Co February 26 Lunch Served At 11:00 AM • Sale Starts 1:00 PM 50 Registered Angus […]

The event features research updates and educational presentations.

Live Streaming Auction - February 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - February 27, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

Moving Back Home! In addition to our yearling bulls, we also added some age-advantage bulls. The sale will take place at the Lewiston Roundup Grounds, just South of Lewiston. Both […]

FRIDAY – February 28, 2025 / 8:30 AM 17129 HIGHWAY 99 NE, WOODBURN, OR 97071 AUCTION DETAILS: Auction Begins: Friday – February 28th, 2025 @ 8:30 AM – (PST) Live-online […]

Trinity Farms BETTER BULLS. BRIGHTER FUTURES. Trinity composite bulls, the perfect solution for advanced beef production. 250 Bulls Available Ellensburg, WA • 3.1.2025 www.trinityfarms.info • (509) 201-0775

Preview: Sat. March 1st 9am - 1 pm Biddings Ends: Thurs. March 6th Starting at 6pm Highlights Include: Bulb planter and harvest equipment, disks, plows, harrows, cultipackers, 4 row planter, […]

Heavy Equipment • Tractors • Construction • Farm Equipment • Vehicles • Trucks • Trailers & More! Virtual Online-Only Auction Full Catalog & Bidding Procedures Available at www.yarbro.com Start […]

Booker's Annual Early Spring Eltopia Auction March 6-7, 2025 www.BookerAuction.com | 509.297.9292

2-Day Online Equipment Auction @ Meridian Equipment Auction CO, Bellingham WA. Now Accepting Quality Machinery Consignments AUCTION INFORMATION Online Only Bidding ONLINE BIDDING OPENS: Feb 22, 2025 DAY 1- Online […]

Oregon State University Surplus hosts Annual Farm Sale Bid on 30+ years of local farm surplus! Join OSU Surplus on March 8th at the Lewis Brown Farm in Corvallis for the […]

Join us for the Genetic Edge Bull Sale! 320 Coming Two-Year-Old Bulls • 265 Yearling Bulls • 305 Calving-Ease Bulls Schedule of Events Friday, March 7, 2025 All Day […]

March Online Equipment Consignment Auction Online Bidding is Wed, March 12th - Wed, March 19th Chehalis Livestock Market 328 Hamilton Rd. N., Chehalis, WA 98532 Follow Us on Facebook! @Chehalis […]

Online Auction - March 12th Bid Now! Dairy, Farm, Excavation & Heavy Equipment, Transportation, Tools, & More! Magic Valley Auction MVAidaho.com 208-536-5000

Bidding starts on Wednesday, March 12th Go to www.clmauctions.com and click on Hibid link to view and bid on over 1,000 lots! Lots of great pickups, trailers, tractors, cars, farm trucks, haying […]

ONLINE ONLY AUCTION Schritter Farms Retirement Auction Bidding Now Open! Bids Begin Closing on March 12th @ 9AM MST Multiple Locations - Please See Individual Lots For Their Specific Location, […]

Thursday, March 13th at 9:30 AM ~ Bill Miller Rentals ~ Rubbered Tired Loaders, Crawler Tractors, Cranes, Motor Graders, Haul Trucks, Excavators, Water Trucks, Truck Tractors, Trailers, Attachments and Support […]

RAM RIDGE LLC & PALM CONSTRUCTION - ONLINE AUCTION Aggregate Crushing & Heavy Equipment Start Date: 10AM | Thursday - March 13 End Date: 10AM | Thursday - March 20 […]

Thursday, March 13th at 9:30 AM Rubber Tired Loaders, Crawler Tractors, Cranes, Motor Graders, Haul Trucks, Excavators, Water Trucks, Truck Tractors, Trailers, Attachments and Support Equipment Carlin (Elko), Nevada HIGHLIGHTS: […]

March 14th - March 18th 2025 Changes Farm Operations Maxwell, CA Learn more at AUCTION-IS-ACTION.COM Putnam Auctioneers, Inc. CA Bond No. 7238559 Email: putman.kevin@yahoo.com John Putnam - (530) 710-8596 Kevin […]

Saturday, March 15th 9:30 AM Address: 1800 West Bonanza Rd., Las Vegas, NV 89106 Highlights: 2-Tele. Forklifts: Unused JLG 943, Unused JLG 742, 2-Cab & Chassis: (2)Unused Chevy 5500, 3-Detachable […]

March Online Auction Begins to close @3pm MST | March 17, 2025 Early Listings: *2017 Bobcat 418-A-A Mini Excavator, *International 544 Utility Tractor with Loader, *2016 Bobcat E20 Mini Excavator, […]

Multi-Seller - Open Consignment Bidding Now Open - Additional Items Arriving Daily Starts Closing: Tuesday, March 18th @ 2PM (MT) Tractors • Trucks • Trailers • Construction Equipment • Farm […]

Machinery Auction March 19 & 20 All lots start to close at 8:00 a.m. PST Online Bidding Opens March 14 at 3:00 p.m. PST Items include: Construction Equipment, […]

12:30PM Wednesday, March 19, 2025 Performance Tested Bulls: Angus, Simmental and SimAngus, Red Angus, Charolais 90 Day Breeding Guarantee. Western Breeders Assoc. Bonina Feed and Sale Facility, 430 Ferguson Lane, […]

Booker's Annual Early Spring Offsite Farm Auction Ends March 19, 2025 www.BookerAuction.com | 509.297.9292

MAJOR CONSIGNORS: Twin Falls Highway District; KWS Seeds; Molyneux Family Farms; and Sev'rl Area Farmers throughout the Magic Valley NOTICE: Items listing in this auction are located at multiple locations […]

Saturday, March 22, 2025 • At the Ranch • Sandpoint, ID High maternal easy fleshing Cows Low maintenance Heifers High performance Bulls Selling 47 Bulls and 40 Open Heifers […]

Discover the Estate of Afton Jacobson, offering 743± acres of farmland just 4 miles south of Pullman, WA. This expansive property features 6 parcels, two including residences and outbuildings, providing […]

Live Streaming Auction - March 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - March 27th, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

March 28th, 9:00 am - 5:00 pm March 29th, 9:00 am - 3 pm The 4th Annual Central Oregon Agricultural Show presents the best of the region’s agricultural industry. The […]

FRIDAY – March 28, 2025 / 8:30 AM 17129 HIGHWAY 99 NE, WOODBURN, OR 97071 AUCTION DETAILS: Auction Begins: Friday – March 28th, 2025 @ 8:30 AM – (PST) Live-online […]

Bids Open at 3pm PST on March 20th Start Closing at 8am PST, April 2 & 3, 2025 On-Site Preview available Monday to Saturday from 9am to 4pm Visit www.I-5auctions.com […]

Located: 3021 N 2800 W, Brigham City, Utah 84302. Take Exit 365, go west 1 1/2 mile to 2800 W, turn north 1 1/2 a mile to auction site. Watch […]