ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 6:45 am Thursday, October 3, 2019

BOARDMAN, Ore. — A thousand miles separates Threemile Canyon Farms in Eastern Oregon, surrounded by high desert and sagebrush, from the crowded freeways of Los Angeles.

Though they might seem like distant strangers, the mega-dairy and the megalopolis are about to be connected by a most unexpected resource — cow manure.

Threemile Canyon Farms is Oregon’s largest dairy with 68,340 cattle, including 33,000 milking cows. In 2012, the farm built an anaerobic digester to capture methane emissions from all that manure. It has since used the gas to generate electricity, which it sells to the interstate utility PacifiCorp.

In June, state regulators approved an expansion of the facility, and Threemile Canyon installed new equipment to purify the methane. Farm managers now plan to inject it into a nearby natural gas pipeline, which will transport it to Southern California to produce cleaner-burning fuel for trucks.

“Renewable natural gas is gaining a lot of momentum in the marketplace,” said Marty Myers, general manager of Threemile Canyon Farms. “It’s a highly valuable renewable fuel.”

Myers and others described the system as a best management practice for dairies to reduce air pollution that contributes to climate change and provides a new revenue stream in the face of low milk prices. But environmentalist opponents argue renewable natural gas is an inherently dirty energy source supporting unsustainable large farms.

‘This is modern farming’

The digester complex at Threemile Canyon overlooks rows of free-stall barns where cows wait to be milked at the 93,000-acre farm west of Boardman.

Rick Morck, a consultant and engineer who helped design the digester, stood in the control room where workers monitor the production of biogas 24/7. Every step of the process is automated.

“This whole operation, nothing passes through that isn’t used, reused or optimized,” Morck said.

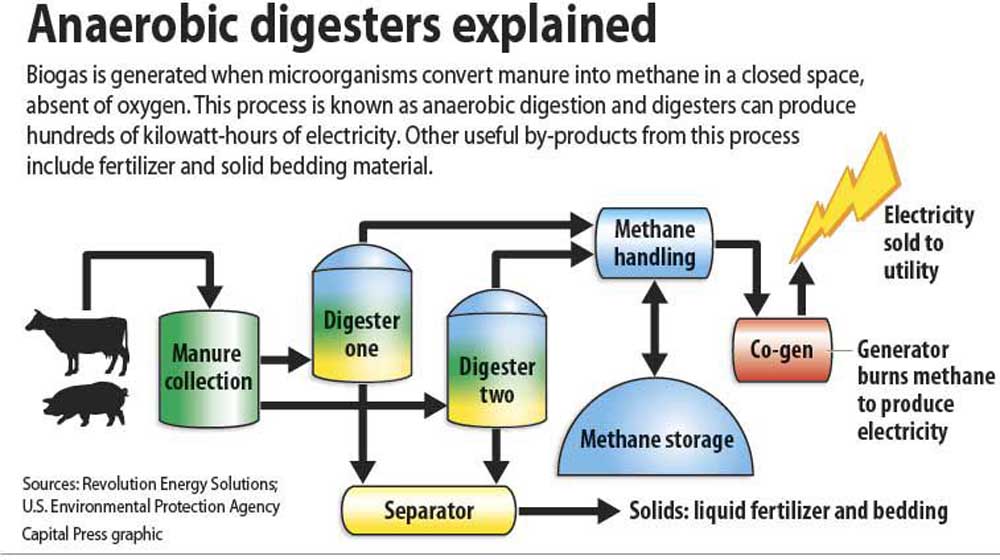

It starts with flushing manure from the barns, which is done four times a day. The sludge collects in a large concrete lagoon, and is then pumped through a series of rotating screens to remove most solids. From there, it goes into settling tanks known as clarifiers, and finally to 30-foot-deep stilling basins where anaerobic digestion occurs.

The basins look like two large half-inflated air mattresses, capable of holding a combined 15 million gallons of manure. A thick vinyl cover traps the harmful gas emissions.

During the digestion process, bacteria and microorganisms break down the manure at 100 degrees over 23 days, giving off mostly methane and carbon dioxide. It is currently used to fire three generators capable of producing up to 4.8 megawatts of electricity — enough power for a city the size of nearby Boardman, population 3,329.

The remaining dried solids are also recycled to make animal bedding, which has the texture and feel of sawdust. It can also be used as a nutrient-rich soil amendment.

Leftover liquid is reused as clean water to flush out the barns, starting the process anew.

“It’s really amazing,” Morck said. “This is modern farming.”

Tapping into the pipeline

Earlier this year, Threemile Canyon Farms asked the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality for permission to expand and retrofit the digester complex with new technology.

DEQ approved a modified air quality permit for the facility in July, despite objections from 10 environmental groups.

A third stilling basin is now under construction at the farm, which would add the capacity for another 6 million gallons of manure. With the two other basins, it will be able to handle all manure from the farm’s entire milking herd.

More importantly, Myers said, the farm is already finished installing new equipment to convert the methane to “pipeline quality” natural gas, removing carbon dioxide and other impurities.

Threemile Canyon partnered with Equilibrium Capital, a Portland investment firm, on the $30 million project. Iogen Corp., a Canadian biotech firm, has marketed the gas to companies that plan to make transportation fuel.

Renewable natural gas, or RNG, reduces carbon dioxide emissions by 80% or more compared to diesel, according to the Coalition for Renewable Gas. RNG also qualifies for tax credits under the federal Renewable Fuel Standard, further incentivizing production.

Myers said the farm began injecting natural gas into an interstate pipeline in late July. The line was extended through Threemile Canyon in 2016 to service the Carty Generating Station, a 440-megawatt natural gas power plant south of Boardman owned by Portland General Electric.

“When we gave them the easement to do that, part of the negotiation was we would be able to tap into that pipeline,” Myers said.

RNG market

Renewable natural gas has become an increasingly attractive market over the last five years, thanks a combination of incentives and lower electricity prices.

Craig Frear, director of research and technology for Regenis — a company based in Ferndale, Wash., that specializes in building and operating digesters on farms — said RNG has emerged as a better value proposition compared to electricity.

“These developers are knocking on the doors of dairymen,” Frear said.

Regenis built its first manure digester in 2004 at Vander Haak Dairy in Lyndon, Wash. Since then, the company has built and maintained 13 digesters in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and California.

Frear said business hit a lull between 2012 and 2016, as drillers began extracting more natural gas by hydraulic fracking, which led to a drop in gas and electricity prices. Digester projects that once earned 8-10 cents per kilowatt-hour for the electricity they produced were now lucky to get 5 cents per kilowatt-hour, which is near or below the cost of maintenance.

“That was enough to strongly curtail the electric-to-grid business plan,” Frear said.

Digesters can be costly. The Environmental Protection Agency generally recommends farms have at least 500 cattle or 2,000 hogs for them to be feasible. Construction costs are about $2,000 per animal, Frear said, which quickly adds up to millions of dollars, depending on size.

The industry looked toward a new model. Due to its smaller carbon footprint, RNG qualifies as an advanced biofuel under the federal Renewable Fuel Standard, a federal program that requires transportation fuel to contain a minimum volume of renewable fuels to help curb greenhouse gas emissions.

Under the program, RNG is eligible for biofuel credits that companies can market and sell. Individual states, such as Oregon and California, also offer credits through their Low Carbon Fuel Standard programs, adding to the potential value.

Manure from hogs and cattle can be particularly high-value, Frear said, because of its lower carbon index score. On-farm digesters are actually carbon-negative, meaning they divert carbon that would otherwise go into the atmosphere.

Frear said dairy gas can fetch the equivalent of up to 20 cents per kilowatt-hour of electricity — four times more than the 5 cents earned by electric-to-grid.

Potential for growth

Patrick Serfass, executive director of the American Biogas Council, said there is massive potential for industry growth.

There are 2,200 biogas systems in operation across the country, including 250 farm-based digesters, 1,300 systems at wastewater treatment plants, 80 stand-alone food scrap digesters and 600 at landfills, Serfass said.

The American Biogas Council, EPA and USDA predict there is enough capacity to add 14,000 biogas projects. That includes 8,000 farm digesters.

“We have so much organic material to deal with,” Serfass said, pointing to 31 billion gallons of wastewater every day and manure from 8 billion cows, chickens, turkeys and hogs.

“None of those numbers are going down,” he said. “We have to develop the infrastructure to handle all that material.”

Historically, digesters were installed primarily to reduce odor, Serfass said, but the benefits they provide are multi-faceted.

Digesters kill 99% of the pathogens in manure and wastewater while capturing methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Not only can the gas be recycled as renewable fuel, but the digested fiber is useful as animal bedding and fertilizer, he said.

He pointed to Magic Dirt, a company in Idaho that makes organic potting soil from digested fiber. According to the company, 10 cubic feet of Magic Dirt sequesters approximately a third-ton of greenhouse gas, and the product is capable of holding three times its dry weight in moisture.

“We’re trying to do a lot of education to help farmers and all of these sectors to understand the many benefits that come from a biogas system,” Serfass said. “It becomes very obvious about how beneficial these systems are.”

A false solution?

Environmental groups are wary of creating more biogas systems, which they argue are a “false solution” to climate change and a ruse to build more large farms.

Food & Water Watch, an organization based in Washington, D.C., issued a five-page report earlier this year against producing biogas from farm waste, calling it “dirty energy.”

Burning biogas still releases carbon dioxide, the report states, along with smog-forming pollutants such as nitrogen oxide, ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, potentially offsetting other greenhouse gas reductions.

The report also raises concerns about accidental leaks from manure digesters, as happened in July at the Port of Tillamook Bay along the Oregon Coast. A digester at the port spilled 300,000 gallons of liquid waste, some of which entered a nearby storm water pipe. All but a small amount of digestate was recovered.

Oregon regulators tested for bacteria in Tillamook Bay, and found there was no public health risk.

Tarah Heinzen, senior attorney at Food & Water Watch, said she worries digesters producing RNG will increase the country’s reliance on “unsustainable factory farms” that are significant polluters.

“Digesters are really only technologically feasible, much less economical, for the very largest factory farms,” Heinzen said. “It’s the confinement, and the liquid waste storage, that leads to the large amount of greenhouse gases being emitted from this industry in the first place.”

Serfass pushed back against the claims, saying digesters can make a farm of any size more environmentally friendly.

Frear, who also serves on the American Biogas Council’s Board of Directors, said that while no one technology can solve every environmental problem, he believes digesters are sustainable in the long term.

“I personally believe climate change is a real and imminent threat,” Frear said. “Anaerobic digestion or production of renewable natural gas checks a lot of boxes.”

Myers, at Threemile Canyon Farms, said RNG production does offer the dairy some savings and revenue, but not enough to encourage them to expand their cow herd, even with lower milk prices. He also expects the value of tax credits will depreciate over time as more projects come online.

“It’s just an additional adaptation by this farm to increase our best management practices and reduce our emissions,” he said. “It is really being driven by people trying to reduce the carbon footprint of their operations. And they’re being encouraged to do that.”