ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 9:00 am Thursday, December 6, 2018

Though the U.S. Forest Service didn’t say so outright, Matt McElligott and other ranchers who graze cattle in Oregon’s Malheur National Forest believed they’d been given an ultimatum.

Either bow to the agency’s demands, or lose their grazing rights and suffer financially.

The timing seemed to send a message, McElligott said. The ranchers were given less than a week to comment on the 335-page biological opinion that would govern grazing in the national forest for the next four years.

In the days he had to read the document, McElligott said he found reasons to be alarmed that grazing restrictions would increase, but his back was against the wall.

The Forest Service released the document for ranchers to review in late May, when some would ordinarily have already turned out cattle onto forest grazing allotments. But unless the biological opinion for the Mid-Columbia steelhead — a fish population protected under the Endangered Species Act — was finalized, there could be no grazing.

“If I’d objected, they’d just have put the brakes on it. Nobody would have gone out to graze,” McElligott said.

“If you guys want to turn out,” he inferred, “you just have to accept this.”

Seven months later, having endured one grazing season under the biological opinion, McElligott isn’t optimistic about next year.

Because the Forest Service determined that some ranchers were out of compliance with the plan in 2018, certain repeat violations on those same grazing allotments in 2019 could trigger the need for yet another biological opinion — and with it, further restrictions on the number of cattle that can be turned out and where they can graze.

Ranchers turn out more than 24,000 cow-calf pairs a year between June and mid-October on 111 allotments in the 1.7 million-acre national forest, about 90 percent of which is grazed. The Forest Services estimates grazing generates roughly $200,000 in fees for the federal government and approximately $7.7 million in labor income, which is farm revenues after expenses.

Dissatisfaction with the current biological opinion, which governs grazing from 2018 until 2022, already runs deep among ranchers in the area, with some considering a lawsuit against the federal government over the document’s scientific validity, McElligott said.

“We’ve had issues with the Forest Service before, but nothing like this,” he said.

McElligott and others say they hoped the Trump administration, with its emphasis on deregulation, would be more “reasonable” regarding grazing policy. Two years in, however, they say there’s little evidence of that in the biological opinion.

That’s probably because the deregulation message can have trouble filtering through multiple layers of federal government, said Rep. Greg Walden, R-Ore., whose congressional district includes the national forest.

“This administration is not doing as much as many of us thought it would on the national forests and grazing,” he said. “Driving change through the embedded bureaucracy is very difficult.”

Walden noted the biological opinion is based on a lot of work that occurred before President Trump came into office, setting a foundation that’s tough to budge.

“Some of this has been going on for decades and there’s a lot of momentum behind it,” he said.

If the political route is slow-moving, the legal route isn’t necessarily any faster.

Lawsuits over grazing in the Malheur National Forest are nothing new. Complaints have been filed over the years by environmentalists who claim the government’s biological opinions insufficiently protected the threatened fish species. One case over bull trout was finally thrown out this year after 15 years of litigation, but the decision is now under appeal.

The potential for court battles highlights the complexity federal agencies face when analyzing the effects of grazing on riparian habitats.

In basic terms, the Forest Service develops management plans for regulating grazing to avoid harming fish protected under the Endangered Species Act.

Those plans are then submitted to the National Marine Fisheries Service, which issues a biological opinion determining whether the species or their habitat will be jeopardized by the proposed activity.

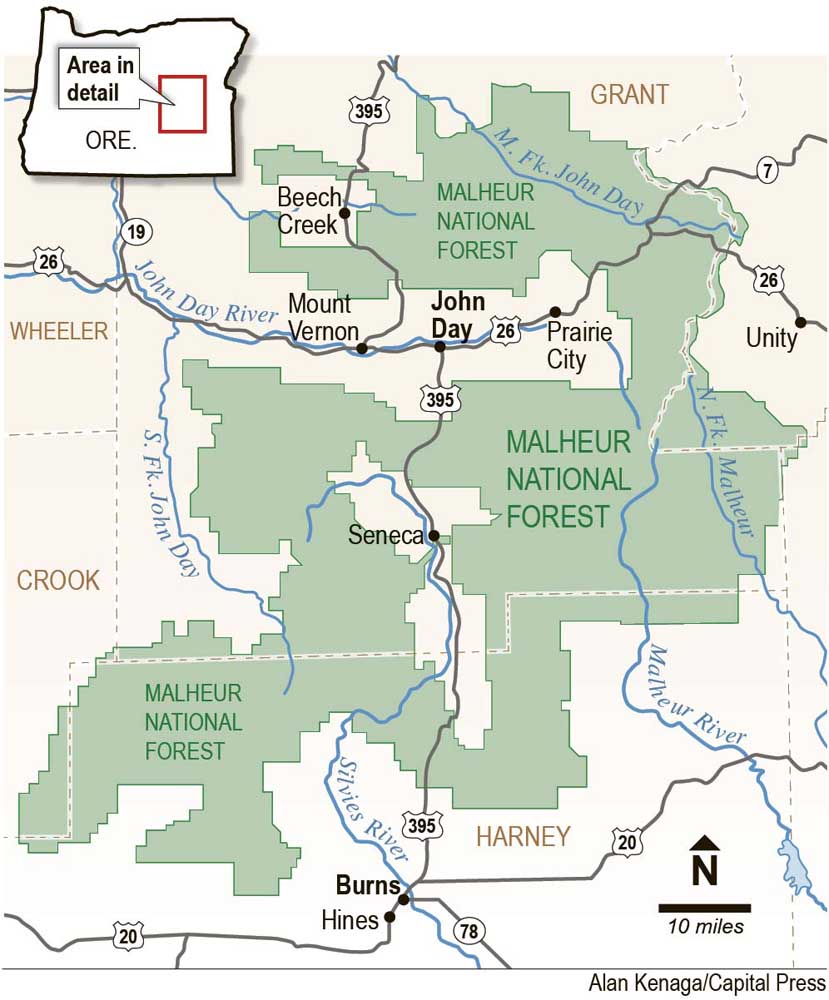

The steelhead population within the tributaries of the John Day River is estimated at roughly 4,500 to 20,000 fish, depending on the year, according to the Forest Service.

In the past, when the agency found the grazing plans were “not likely to jeopardize” steelhead as long as restrictions were followed, environmental activists claimed they were arbitrarily lenient.

Now, ranchers believe those regulations are arbitrarily excessive.

“The problem is the science they used to build this goddamn document,” said Loren Stout, a rancher in the area.

For example, federal agencies have developed their environmental data about steelhead populations by studying areas where fish are unlikely to travel, such as upstream of multiple “check dams” installed by the Forest Service to slow water flow, Stout said.

Though ranchers aren’t responsible for the problem, grazing cattle nonetheless get the blame, he said.

“If you go against their agenda, you’re demonized,” he said.

Ken Holliday, another area rancher, said the biological opinion is just one element in a broader pattern of mismanagement within the national forest.

“Malheur means misery, hopelessness,” he joked, explaining the regional name’s origin among French-Canadian trappers.

For example, riparian fences prized by federal agencies for keeping cattle out of creeks can actually backfire, he said.

A fence across one creek got clogged with scraps of wood and other debris, which accumulated and eventually burst through the structure, severely damaging the stream bank, he said.

Efforts to slow down streams can cause them to become overgrown with sod, whereas steelhead need fine gravel in which to lay their eggs, Holliday said. “What this is, is science gone wrong.”

Some restrictions within the biological opinion haven’t been scientifically validated but are based on decades-old conjectures and theories that have been cited in federal documents so long that they’ve essentially become sacrosanct, said Shaun Robertson, a natural resources consultant who works in the area.

“The more times it’s translated, the more it’s institutionalized,” he said.

Robertson said that’s a symptom of the Forest Service becoming an organization more focused on compiling reports than conducting field work.

“The process is the objective, not the recovery,” he said. “That’s where the jobs are.”

Among the more controversial measures of cattle impacts in the biological opinion is bank alteration, or the percentage of hoof prints on the stream bank. In the most sensitive riparian areas, 10 percent bank alteration triggers the need to move cattle, while more than 15 percent is a violation.

McElligott said he hit the 10 percent threshold in 10 days on one allotment, forcing him to devote manpower to moving cattle instead of rebuilding water structures at several springs, which would keep livestock away from streams.

In the eyes of the Forest Service, it doesn’t matter if the bank alteration was caused by elk or wild horses, he said. Meanwhile, the agency regularly tears up brush along creek banks with heavy machinery when conducting in-stream restoration work.

“That’s what has ranchers upset,” McElligott said. “That’s the hypocrisy and that’s why the permittees are pretty upset.”

Amy Unthank, natural resources and planning officer with the Forest Service, said the agency is aware of complaints about a double standard in regard to restoration work.

However, using heavy equipment to create “analog beaver dams” and rebuild stream channels is a one-time impact to the riparian area from which it quickly recovers — unlike an impact that occurs year after year, she said.

The “log weirs” that dam streams are a “legacy” issue in the forest and a lot of them are being removed, with the agency now mimicking trees naturally collapsing into waterways rather than anchoring them to the ground, Unthank said.

As for tensions about bank alteration, Unthank said they’re largely a matter of stricter enforcement rather than stricter standards — the benchmarks haven’t changed from the previous biological opinion.

“We are trying to be more consistent with our management,” she said.

Unthank said the standards in the biological opinion are based in science, with some measures of impact serving as a proxy of actual “take” — killing or harming — of fish or their habitat.

There has been an uptick in “non-compliance” letters to ranchers, though that doesn’t necessarily mean the frequency of violations has risen, Unthank said.

Rather, the agency is trying to live up to its forest plan standards and Endangered Species Act commitments at the behest of the National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which consult on threatened and endangered species in the forest, she said.

“You guys have an uneven record of enforcing the range policy,” Unthank said, summarizing the two agencies’ concerns about the Forest Service.

Another issue is stubble height, or the length of grass. Along riparian areas it must be no shorter than 6 inches at the end of the season, she said.

That’s more stringent than the previous plan, which allowed stubble height as low as 4 inches in some cases, but it’s still lower than the 6 to 8 inches the consulting agencies had pushed for, Unthank said. “We did not capitulate to that.”

The short amount of time that ranchers had to review the biological opinion was a result of the complexity of putting the document together with a limited number of staffers, she said.

Malheur National Forest’s grazing program is the largest in the region, so gathering information and providing proper documentation took longer than expected, Unthank said.

“Do you really want to review it, ranchers, or do you want to go out and graze, was the hard choice it came down to,” she said.

If the ranchers were permitted to graze their cattle without a biological opinion, they’d have no protection for “incidental take,” or harming, of threatened fish, leaving them vulnerable to environmental lawsuits, said Dale Bambrick, who heads the Columbia Basin NMFS branch of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

While NMFS often gets blamed for more stringent restrictions in the biological opinion, the agency merely approved proposals submitted by the U.S. Forest Service, Bambrick said.

“We’re getting creamed over and over again for metrics we didn’t put in the doggone permit,” he said.

In some respects, such as stubble height and the allowable number of “redds” — fish egg nests — that can be trampled, the new document is actually fairly liberal in favor of grazing, Bambrick said. The previous biological opinion allowed two redds to be trampled, while the current one allows for three.

In the future, NMFS hopes to coordinate with ranchers and the Forest Service more closely to avoid such a drawn-out process for the biological opinion, he said. “It was a mess, but we got through it.”