ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 4:45 pm Monday, August 2, 2021

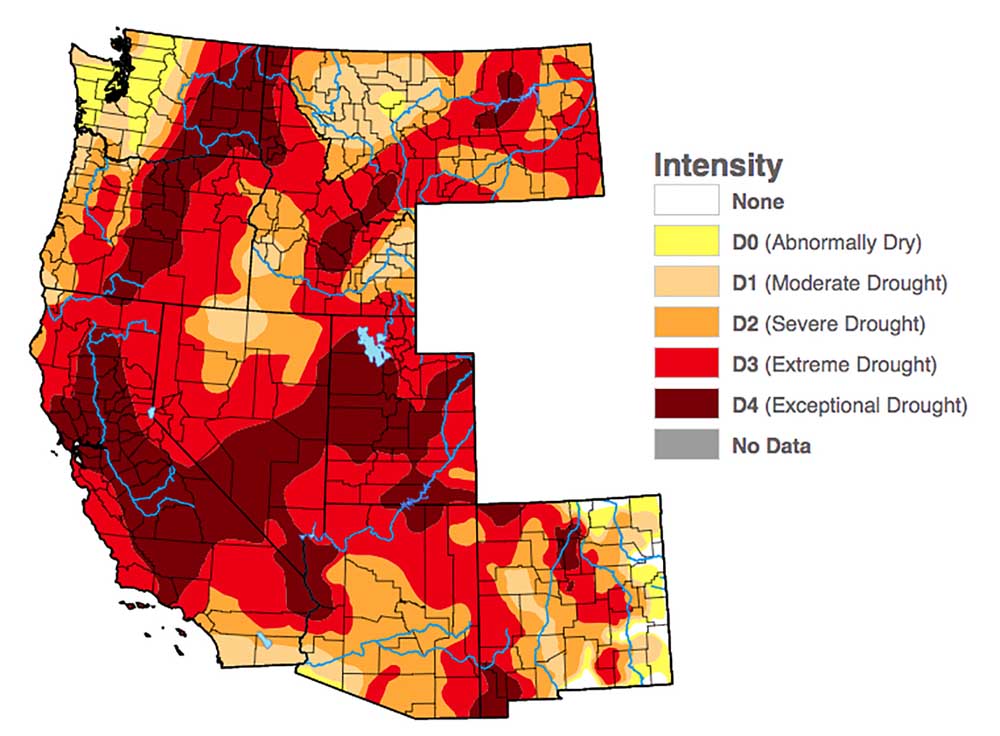

The West has been so dry and so hot for so long that its current drought has no modern precedent, according to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration meteorologist.

For the first time in 122 years of record-keeping, drought covers almost the entire Western U.S. as measured by the Palmer Drought Severity Index, said Richard Heim, a drought historian and an author of the U.S. Drought Monitor.

“It’s a very simple ‘yes,’ in terms of this drought being unprecedented,” Heim said.

The Palmer index estimates relative soil moisture based on temperature and precipitation records. Unlike the Standard Precipitation Index, which measures water supply, the Palmer index also takes into account heat-driven demand for water.

In June, about 97% of the West — Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah and Washington — was in water-deficit territory, according to the Palmer index.

Utah was never drier, while Oregon and California were at their second driest on record. Idaho and Arizona were at their third driest ever, and Nevada was at its fourth driest.

Washington was at its 10th driest, while Montana and New Mexico, where recent monsoons have brought relief, were at their 17th driest.

Oregon and Washington state climatologists gave their qualified endorsement for calling this drought “unprecedented.”

“I’d be slightly cautious about calling it ‘unprecedented,’ but that’s probably a fair description,” Oregon State Climatologist Larry O’Neill said. “It’s borderline unprecedented, or at least among the worst.”

The cumulative effects of the West’s current drought, illustrated by low major reservoirs, gives credence to calling it unprecedented, Washington State Climatologist Nick Bond said.

“I don’t have any real quarrel with using that term,” he said.

The Drought Monitor, a partnership between NOAA and the USDA, has been mapping drought in the U.S. since 2000. The percentage of the West in “exceptional drought,” the worst category, has never been higher. More than 95% of the nine Western states is in some stage of drought.

Heim said the combination of prolonged above-average temperatures and below-normal precipitation set this drought apart from two multiyear droughts that spanned the 1930s and 1950s.

The U.S. entered another extended dry episode in 1998, he said. The drought has eased periodically, but never really went away and reasserted itself beginning last spring, he said.

A 24-month period that ended June 30 was the driest such two-year period ever in the West, according to records dating back to 1895. The same time period was the sixth warmest.

Other two-year dry periods, such as 1976 and 1977, were not as hot, Heim said.

“I would define this (drought) as still part of a 20-plus-year drought,” he said. “In the last year and a half, we have been on an intensifying trend.”

The drought’s depth, duration and cause varies by state, making comparisons between the current drought and past droughts imperfect.

In measuring drought, “there is no simple best way,” Bond said. “There are different flavors of drought.”

Washington’s 1977 drought was much worse judged solely by the precipitation index. About 90% of Washington was in exceptional drought in June 1977, compared to less than 1% this June.

Idaho and Oregon also were in deeper droughts in June 1977 than this year, according to the precipitation index. California, however, is worse off this year.

Long dry spells lead to hydrological droughts, when streams and reservoirs are low and wells are dry.

Southern Oregon has fallen into a hydrological drought, and it will take a long time to recover, O’Neill said.

“Even if we get normal precipitation in the winter, we would expect to be in at least moderate hydrological drought next year,” he said.

The federal Climate Prediction Center says that odds favor a La Nina forming next winter. The climate phenomenon generally means a good snowpack in Washington and a poor snowpack in Northern California.

In Oregon, La Nina often has less pronounced effects, O’Neill said. The dividing line between good and poor snowpacks in La Nina years falls about Roseburg, he said.

“I think the bottom line is we can’t necessarily depend on La Nina for saving us from drought,” he said.

Washington’s 2015 drought started with a warm winter and low snowpack during an El Nino, which has the opposite effect from a La Nina.

The “snowpack drought” led to low stream flows. The drought this year was brought on by a dry spring. Melting snow continued to supply streams.

The 2015 drought was worse for Washington irrigators and a “better example of a climate-change drought,” Bond said.

“It’s going to be the kind of drought we’re going to have because of climate change,” he said.