ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 4:15 pm Thursday, May 19, 2022

While a cool and wet spring has aided drought recovery in parts of the Northwest, climate experts in Oregon, Washington and Idaho say conditions remain critically dry in other areas with little chance of bouncing back before summer.

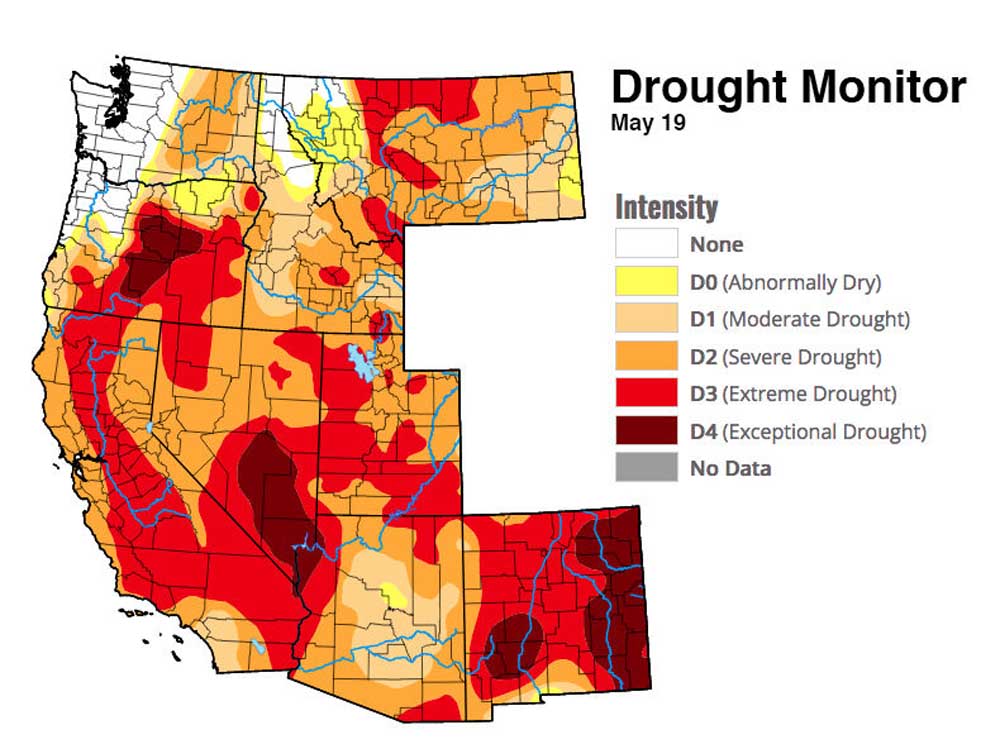

Nearly 70% of the region is in some stage of drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, with 20% in “extreme” or “exceptional” drought, the two driest categories.

The most severe drought continues to be in central and southern Oregon, eastern Washington and southern Idaho. In contrast, all of western Washington and Oregon’s Willamette Valley were pulled out of drought thanks to record April rainfall.

Larry O’Neill, Oregon state climatologist, said last year had the driest spring on record statewide. This year, however, he expects the drought will be more regionally focused.

“Much of Oregon is still in drought, even though we’ve experienced this great springtime precipitation,” O’Neill said. “Only a couple parts of the state received above-normal precipitation. The rest of the state did not receive adequate precipitation.”

O’Neill was joined by Nick Bond, Washington state climatologist, and David Hoekema, hydrologist for the Idaho Department of Water Resources, during a webinar on May 18 detailing the latest drought conditions and outlook for the Northwest.

The meeting was conducted under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Integrated Drought Information System, which was created in 2006 to coordinate regional drought monitoring, forecasting and planning.

Lingering drought across much of Oregon is also due in part to well below-average precipitation, warmer weather and inadequate snowpack over the last three years, O’Neill said.

The big exception is northwest Oregon, where Portland had 5.6 inches of rain in April, setting a record. Parts of Umatilla, Union and Morrow counties in northeast Oregon have also mostly recovered from drought after receiving 125% of normal precipitation for the water year dating back to Oct. 1.

But in the most drought-stricken areas of central and southern Oregon, O’Neill said conditions are even worse than last spring.

On April 29, the Bureau of Reclamation reported water storage in Prineville Reservoir was 28%, the lowest ever recorded for the time of year. Since then, the reservoir storage has increased slightly, to 32%. Wickiup Reservoir near Bend also remains less than half filled, at 46%.

Streamflows in the Upper Deschutes and Crooked River basins are expected to range from 44% to 90% of normal through the irrigation season, according to the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, all but ensuring lackluster water supplies for irrigators.

“We expect those conditions will continue into summer and next fall,” O’Neill said.

If drought has divided Oregon and Washington from east to west, then it has done the same in Idaho from north to south.

Gov. Brad Little has declared a drought emergency in 34 of 44 counties — all in central and southern Idaho.

“That drought declaration is particularly aimed at giving irrigators the ability to do emergency transfer of water rights in an expedited manner so they can have one more tool to deal with the drought,” Hoekema said.

Hoekema said April precipitation provided a much-needed boost for several key river basins in the region, particularly the Weiser, Payette, Boise, Big Wood and Snake River basins, which all received between 135% and 146% of normal precipitation for the month.

The Snake River above Heise has gained approximately 200,000 acre-feet of streamflow into reservoir storage, Hoekema said. However, that was still not enough to ensure an adequate irrigation supply given last year’s low carryover.

“We still expect (water) shortages across Southern Idaho,” Hoekema said.

April was the third-coldest and tenth-wettest on record for Washington as a whole, though Bond said overall precipitation for the last 90 days still suggests drier than normal conditions east of the Cascades.

Going back even farther, records show that between May 2020 and April 2022, Grant and Lincoln counties experienced their eighth- and sixth-driest conditions on record for that two-year period, respectively.

The chances of ending drought across eastern Washington in the next four months are slim, Bond said, ranging from just 1% to 20% as the region enters its typical dry season.

Reclamation is predicting full irrigation supplies for the Yakima Basin, though Jeff Marti, drought coordinator for the Washington Department of Ecology, told the Yakima Herald-Republic there could be water restrictions in the coming months for the Okanogan, Spokane and Walla Walla basins.

Drought doesn’t only impact surface water irrigation. Bond highlighted one groundwater well near Davenport, west of Spokane, where the U.S. Geological Survey has recorded water depth dropping from just over 30 feet below ground in 2017 to more than 45 feet below ground this year.

“This is significant, because there are a lot of small water systems in Washington that rely on shallow wells like this one,” Bond said. “This groundwater also supplies water for springs and small creeks. … These long-term declines are another reason why we’re concerned about water availability in the summer coming up.”