ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 7:30 am Wednesday, December 5, 2018

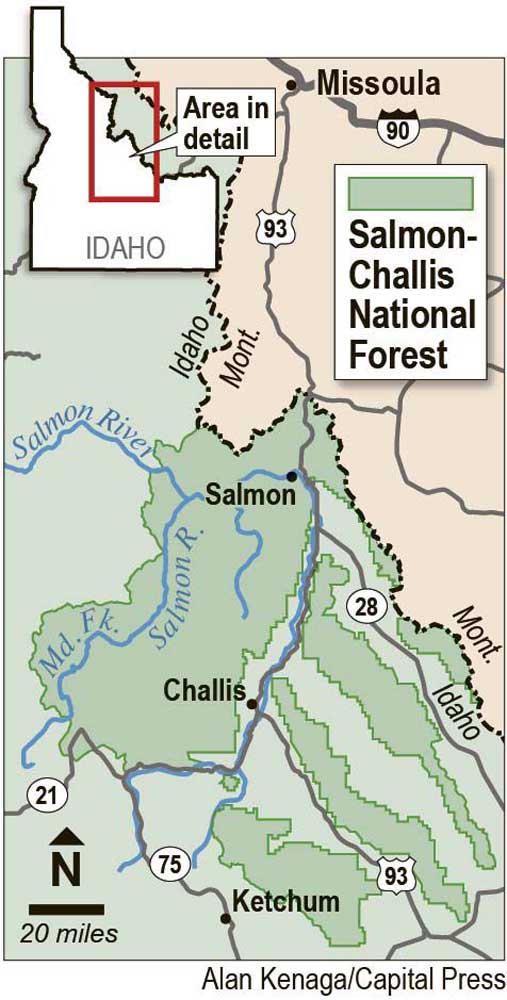

Ranchers in Idaho have filed six lawsuits against the U.S. Forest Service seeking to confirm their rights to divert and convey water from federal property.

Each lawsuit represents one or more farmers, ranchers and agricultural companies that derive their water rights from waterways in the Salmon-Challis National Forest.

The litigation was instigated by the plaintiffs learning the U.S. Forest Service “may assert the right to control” their water rights by “exercising dominion and control” over points of diversion and ditches on the government’s land, according to a complaint.

The complaints seek to confirm the plaintiffs have the right to continue diverting water and to assert “quiet title” to use existing rights of way across public land, said Albert Barker, an attorney representing several plaintiffs.

The underlying controversy began earlier this year, when the Idaho Conservation League filed a lawsuit against the Forest Service, said Nate Helm, whose in-laws run the Arrow A Ranch.

Arrow A Ranch and other affected ranches have sought to intervene in the case to protect their interests as the Salmon Headwaters Conservation Association, but the federal judge overseeing the case has only partially granted that request, he said.

In its complaint, the Idaho Conservation League argues that tributaries of the Salmon River are crucial habitat for federally protected salmon, steelhead and bull trout that can be harmed or killed by irrigation diversions and ditches.

Despite this threat, the Forest Service has never conducted an inter-agency consultation to ensure against jeopardizing these fish species with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service, as required by the Endangered Species Act, the complaint said.

Aside from potentially diverting fish into “inhospitable canals,” diversion structures pose other hazards, such as making downstream habitat less suitable for the species, according to the environmental group.

“Diversions reduce the wetted width and depth of streams below the diversion structure, which increases water temperature and reduces the amount of water available in side channels for fish habitat,” the complaint said.

Chief U.S. District Judge Lynn Winmill said he recognized the affected ranchers have a “significant protectable interest” in their water rights, which could be impeded if the environmental group succeeds in compelling the Forest Service to conduct an inter-agency consultation.

Even so, the judge said the ranchers haven’t shown it’s necessary for them to intervene regarding whether the Forest Service is liable for conducting a consultation, and thus limited their participation to a potential “remedies” phase about correcting the agency’s alleged misconduct.

Helm said he’s optimistic about the ranchers’ legal prospects given a 2004 ruling from the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals which set a precedent that’s favorable to irrigators.

In that decision, the 9th Circuit held that a federal agency no longer had authority over water diversions and therefore wasn’t required to consult on their effects under the Endangered Species Act.

At this point, however, the Forest Service isn’t recognizing the ranchers’ rights-of-way, which is what prompted them to file the lawsuits, said Jon Christianson, an affected rancher.

“You don’t get to stick your head in the sand and claim the benefit of ignorance,” Christianson said of the government’s position. “It seems like a perversion citizens are forced to sue the government to recognize the rights the government gave them.”

As for the environmental lawsuit’s claims about the adverse impacts of diversions, Christianson said the diversions are screened so as not to hurt fish.

Also, dams, reservoirs and off-shore fishing and ocean conditions are having a bigger impact on fish populations, since fish aren’t making it that far upstream, he said.

“What they’re asking for isn’t really going to affect salmon,” Christianson said.

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Featuring quality surplus farm and dairy equipment from farming operations and dealers across Western, WA. Highlights include sellers from Lynden to Snohomish featuring equipment from Farmers Equipment, Inc., Cleave Farms, […]

Bid Now! Bidding Ends March 12, 10 AM MST Dairy, farm, excavation & heavy equipment, transportation, tools, & more! Register Now! Magic Valley Auction www.MVAidaho.com 208-536-5000

Treasure Valley Livestock Auction Caldwell, Idaho Free Delivery within 400 Miles February 25th, 2025 @ 1PM MST VIEW/BID LIVE ON THE INTERNET: LiveAuctions.TV Find us on Facebook at: Idaho […]

The in-person and virtual conference will feature more than 90 speakers, as well as presentations, panel discussions and networking. Organic Seed Alliance (OSA), along with partner Oregon State University’s Center […]

Live Streaming Auction - February 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - February 27, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

Range-Raised • Feedlot-Tested • Carcass-Measured • DNA Evaluated Price Cattle Company with Murdock Cattle Co February 26 Lunch Served At 11:00 AM • Sale Starts 1:00 PM 50 Registered Angus […]

The event features research updates and educational presentations.

Live Streaming Auction - February 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - February 27, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

Moving Back Home! In addition to our yearling bulls, we also added some age-advantage bulls. The sale will take place at the Lewiston Roundup Grounds, just South of Lewiston. Both […]

FRIDAY – February 28, 2025 / 8:30 AM 17129 HIGHWAY 99 NE, WOODBURN, OR 97071 AUCTION DETAILS: Auction Begins: Friday – February 28th, 2025 @ 8:30 AM – (PST) Live-online […]

Trinity Farms BETTER BULLS. BRIGHTER FUTURES. Trinity composite bulls, the perfect solution for advanced beef production. 250 Bulls Available Ellensburg, WA • 3.1.2025 www.trinityfarms.info • (509) 201-0775

Preview: Sat. March 1st 9am - 1 pm Biddings Ends: Thurs. March 6th Starting at 6pm Highlights Include: Bulb planter and harvest equipment, disks, plows, harrows, cultipackers, 4 row planter, […]

Heavy Equipment • Tractors • Construction • Farm Equipment • Vehicles • Trucks • Trailers & More! Virtual Online-Only Auction Full Catalog & Bidding Procedures Available at www.yarbro.com Start […]

Booker's Annual Early Spring Eltopia Auction March 6-7, 2025 www.BookerAuction.com | 509.297.9292

2-Day Online Equipment Auction @ Meridian Equipment Auction CO, Bellingham WA. Now Accepting Quality Machinery Consignments AUCTION INFORMATION Online Only Bidding ONLINE BIDDING OPENS: Feb 22, 2025 DAY 1- Online […]

Oregon State University Surplus hosts Annual Farm Sale Bid on 30+ years of local farm surplus! Join OSU Surplus on March 8th at the Lewis Brown Farm in Corvallis for the […]

Join us for the Genetic Edge Bull Sale! 320 Coming Two-Year-Old Bulls • 265 Yearling Bulls • 305 Calving-Ease Bulls Schedule of Events Friday, March 7, 2025 All Day […]

Online Auction - March 12th Bid Now! Dairy, Farm, Excavation & Heavy Equipment, Transportation, Tools, & More! Magic Valley Auction MVAidaho.com 208-536-5000

March Online Equipment Consignment Auction Online Bidding is Wed, March 12th - Wed, March 19th Chehalis Livestock Market 328 Hamilton Rd. N., Chehalis, WA 98532 Follow Us on Facebook! @Chehalis […]

Bidding starts on Wednesday, March 12th Go to www.clmauctions.com and click on Hibid link to view and bid on over 1,000 lots! Lots of great pickups, trailers, tractors, cars, farm trucks, haying […]

ONLINE ONLY AUCTION Schritter Farms Retirement Auction Bidding Now Open! Bids Begin Closing on March 12th @ 9AM MST Multiple Locations - Please See Individual Lots For Their Specific Location, […]

Thursday, March 13th at 9:30 AM Rubber Tired Loaders, Crawler Tractors, Cranes, Motor Graders, Haul Trucks, Excavators, Water Trucks, Truck Tractors, Trailers, Attachments and Support Equipment Carlin (Elko), Nevada HIGHLIGHTS: […]

RAM RIDGE LLC & PALM CONSTRUCTION - ONLINE AUCTION Aggregate Crushing & Heavy Equipment Start Date: 10AM | Thursday - March 13 End Date: 10AM | Thursday - March 20 […]

Thursday, March 13th at 9:30 AM ~ Bill Miller Rentals ~ Rubbered Tired Loaders, Crawler Tractors, Cranes, Motor Graders, Haul Trucks, Excavators, Water Trucks, Truck Tractors, Trailers, Attachments and Support […]

March 14th - March 18th 2025 Changes Farm Operations Maxwell, CA Learn more at AUCTION-IS-ACTION.COM Putnam Auctioneers, Inc. CA Bond No. 7238559 Email: putman.kevin@yahoo.com John Putnam - (530) 710-8596 Kevin […]

Saturday, March 15th 9:30 AM Address: 1800 West Bonanza Rd., Las Vegas, NV 89106 Highlights: 2-Tele. Forklifts: Unused JLG 943, Unused JLG 742, 2-Cab & Chassis: (2)Unused Chevy 5500, 3-Detachable […]

March Online Auction Begins to close @3pm MST | March 17, 2025 Early Listings: *2017 Bobcat 418-A-A Mini Excavator, *International 544 Utility Tractor with Loader, *2016 Bobcat E20 Mini Excavator, […]

Multi-Seller - Open Consignment Bidding Now Open - Additional Items Arriving Daily Starts Closing: Tuesday, March 18th @ 2PM (MT) Tractors • Trucks • Trailers • Construction Equipment • Farm […]

Machinery Auction March 19 & 20 All lots start to close at 8:00 a.m. PST Online Bidding Opens March 14 at 3:00 p.m. PST Items include: Construction Equipment, […]

12:30PM Wednesday, March 19, 2025 Performance Tested Bulls: Angus, Simmental and SimAngus, Red Angus, Charolais 90 Day Breeding Guarantee. Western Breeders Assoc. Bonina Feed and Sale Facility, 430 Ferguson Lane, […]

Booker's Annual Early Spring Offsite Farm Auction Ends March 19, 2025 www.BookerAuction.com | 509.297.9292

MAJOR CONSIGNORS: Twin Falls Highway District; KWS Seeds; Molyneux Family Farms; and Sev'rl Area Farmers throughout the Magic Valley NOTICE: Items listing in this auction are located at multiple locations […]

Saturday, March 22, 2025 • At the Ranch • Sandpoint, ID High maternal easy fleshing Cows Low maintenance Heifers High performance Bulls Selling 47 Bulls and 40 Open Heifers […]

Live Streaming Auction - March 26, 2025 Timed Auction (Online Only!) - March 27th, 2025 View Catalogs: Day 1 | Day 2

FRIDAY – March 28, 2025 / 8:30 AM 17129 HIGHWAY 99 NE, WOODBURN, OR 97071 AUCTION DETAILS: Auction Begins: Friday – March 28th, 2025 @ 8:30 AM – (PST) Live-online […]