ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 7:00 am Thursday, March 4, 2021

Pinned under an upside down 4-wheeler in a dry ravine, 64-year-old farmer David Endorf took inventory. “I was not bleeding. I was sore, but I did not feel I had broken bones,” he said.

But he was trapped, helpless and alone. He hadn’t told anyone where he was going, and his wife wouldn’t expect him home until 7 or 8 that evening.

It had started as a typical summer day in southeastern Nebraska, sunny and humid. But Aug. 18, 2018, is one Endorf will never forget.

“That’s the day I nearly lost my life, and it’s etched in my memory,” he said.

He had been looking forward to the local cooperative’s annual appreciation lunch, which would start at noon.

“They bring in some good barbecue beef and chicken, baked beans and cornbread,” he said.

But he had a chore to do first — take care of the brushy trees lining the creek that runs through his pasture. At about 9 a.m. he loaded his 4-wheeler and 15-gallon spray tank onto the pickup and headed to the pasture.

By 11:15 a.m., he had sprayed for about two hours in an area filled with obstacles, including trees and ravines off the main branch of the creek.

“I started thinking about this good barbecue meal. It became a distraction, I wanted to make sure I allowed myself enough time to get back to the pickup,” he said.

That noon lunch was calling, and it was time to head back.

But then everything took a bad turn.

“The rear wheel of the 4-wheeler went off the side of the ravine. The 4-wheeler, the sprayer and me went over the edge of the ravine with the 4-wheeler on top of me,” he said.

“The real key here is I didn’t take an extra few seconds to turn around and survey my surroundings and how close I was to the ravine,” he said.

Now his left leg was pinned under the 4-wheeler — 7 feet down in a V-shaped ravine with no way to escape or roll the ATV.

“I was trapped,” he said.

First he had to find his glasses. Then he took a mental survey of his condition. His shoulder and side had taken the brunt of the fall.

Fortunately, the cell phone he wore in a pouch on his belt had survived. But who should he call? His wife couldn’t help, and it would take first responders hours to find him in the remote spot on his 2,000-acre farm.

He thought of his neighbors and distant cousin Bob Endorf and his son Drew. Both are on the local fire department’s rescue squad.

He directed them to his location. It took about 25 minutes. Bob and Drew were able to lift the 4-wheeler enough to free Endorf.

“They absolutely couldn’t believe I could walk and wasn’t hurt. All three of us got in our pickups and went and had a good barbecue lunch,” he said.

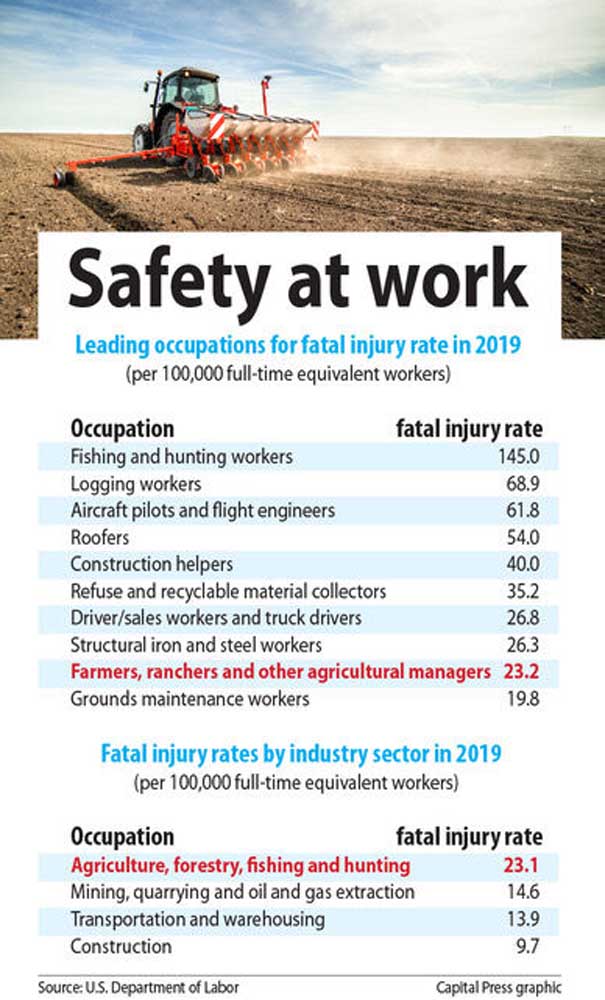

Endorf is one of the lucky ones. Fatal injuries among U.S. agricultural workers totaled 183 in 2019. The number of non-fatal injuries among agricultural workers is no longer tracked at the national level. But in 2015, that number was 167 every day with 5% involving permanent impairment.

Experts say many of the accidents could have been avoided if farmers were more aware of the dangers they face and how quickly accidents can happen.

Endorf went home after lunch, sat his wife, Colleen, down and told her what happened. They took the skid loader to the pasture and pulled the 4-wheeler out of the ravine.

“When she saw that, she just burst into tears and said, ‘How did you survive that?’” he said.

Endorf is grateful he survived and is eager to share his experience. He wants his fellow farmers to be aware of on-farm dangers and ATVs in particular.

“If I can save one person from losing their life or a serious injury than I feel like it’s worth it to tell my story,” he said.

His experience is one of many shared in the Telling The Story Project, which is spreading the message of farm safety through compelling stories of tragic accidents and injuries in the farmers’ words and those of their families.

The project is a joint effort of the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health in Omaha, Neb.; the Great Plains Center for Agricultural Health in Iowa City, Iowa; and the Upper Midwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center in Minneapolis, Minn.

It is funded by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing Program. The project was officially launched in 2018 when the website went live.

The three centers working on the project all have outreach and safety programs and saw an opportunity for telling those compelling stories to raise awareness and prevent accidents, said Scott Heiberger, a health communications manager at the National Farm Medicine Center in Marshfield, Wis., and a member of the outreach team at the Upper Midwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center.

“We saw an opportunity to connect directly with farmers and farm families. We just saw this as a way to meet farmers where they’re at,” he said.

Statistics are helpful and can support the message of farm safety. But personal stories are more effective than a set of numbers, he said.

“People do remember a story, that’s the bottom line. They get their attention and foster farmer-to-farmer discussions. And research shows farmers trust each other more than anyone else,” he said.

The Telling The Story Project is facilitating those discussions by letting farmers tell their personal stories, he said.

Farmers might be inclined to shrug off national statistics, thinking the chance of an accident happening to them is pretty low. But if another farmer is telling them it happened to him and they can see themselves in that story, making the same decisions and taking the same shortcuts, it helps, he said.

They can see that the everyday, mundane things they’ve done a hundred times can still go bad, he said.

“Everyone knows safety is important, but it makes it real,” he said.

Storytelling is a really good way to influence change. Lectures on farm safety aren’t particularly effective, but a neighbor taking extra steps to prevent accidents is, he said.

“The credibility of the storytellers is so important,” he said.

“It all happened so fast,” is a recurring theme in the farmers’ narratives.

Their stories include everyday chores that ended in injury or death due to distraction, hurried action, corner-cutting, missteps, lack of safety gear or lack of awareness.

The injuries range from machinery entanglement and falls to exposure to poisonous hydrogen sulfide gas and explosions.

For some it meant the fight of their life and a long stay in the Intensive Care Unit. For many, it meant surgeries, skin grafts, prosthetics and ongoing physical, respiratory or occupational therapy. For others, it meant an untimely and tragic death.

Their cautionary tales, as told through Telling The Story, carry similar laments:

• They were working alone.

• They didn’t tell anyone where they were.

• They were in a hurry.

• They didn’t have their mind fully on the task.

• They weren’t aware of their surroundings.

• They didn’t take precautions.

• They did something they knew they shouldn’t.

For all of the storytellers — the survivors and the families of those less fortunate — it’s brought new awareness of on-farm dangers, changes to their operations and hard-won advocacy for farm safety.

The farmers take their messages to local events and national conferences, over the airwaves and onto printing presses, and they never miss the opportunity to share with neighbors and other farmers in the local community.

The Telling The Story Project takes a multifaceted approach to spreading the message and has had more than 22,000 visitors to its website.

Project organizers encourage media outlets and other organizations to use the stories to promote safety awareness. The project also offers discussion guides for teachers, 4-H and FFA leaders, farm managers and others looking for ways to start a conversation about safety.

The effort has focused on the Midwest, but other organizations are emulating it with their own storytelling projects. Inspired by the project, the National Children’s Center for Rural and Agricultural Health and Safety has started its own storytelling campaign.

In the meantime, Endorf, the Nebraska farmer, has made several changes to the way he operates. He also has some advice for other farmers.

“I make it a habit to let my wife know where I am,” he said.

Farmers often work alone and in secluded locations. Even if someone were 20 feet away from the scene of his accident, they never would have seen him.

“Let someone know where you’re going to be and what you’re doing,” he said.

He’s also more cognizant than he used to be every time he gets on a 4-wheeler and advises others to do the same.

They’re a very handy tool — all farmers have them, he said.

“We get complacent. We take them for granted, you just hop on them and go. Take a few extra seconds for safety, slow down and think about what can happen,” he said.

His accident was caused by distraction — thinking about that barbecue lunch.

“Keep your mind focused on what you’re doing, on the task at hand,” he said.

He’s also adamant about making sure his cell phone is on his hip and not left in the pickup or on the seat of the tractor — and he makes sure it’s charged.

“When you’re pinned underneath something and can’t move much, you realize pretty fast you need help. It’s important to keep a charged cell phone on you,” he said.

He keeps a photo on his cell phone of his upside down 4-wheeler at the bottom of the ravine. It’s a stark image of the seriousness of the situation and what can happen. People who see it wonder how he survived.

“A guardian angel was looking over me that day,” he said.

He knows he could have easily lost his life.

“Safety is important every day, not only on farms but in our general livelihood,” he said, adding he just returned from a 40-mile trip hauling hay to auction.

“You just have to have safety in the back of your mind all the way around,” he said.

For more information, visit: www.tellingthestoryproject.org