ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 7:00 am Thursday, November 14, 2024

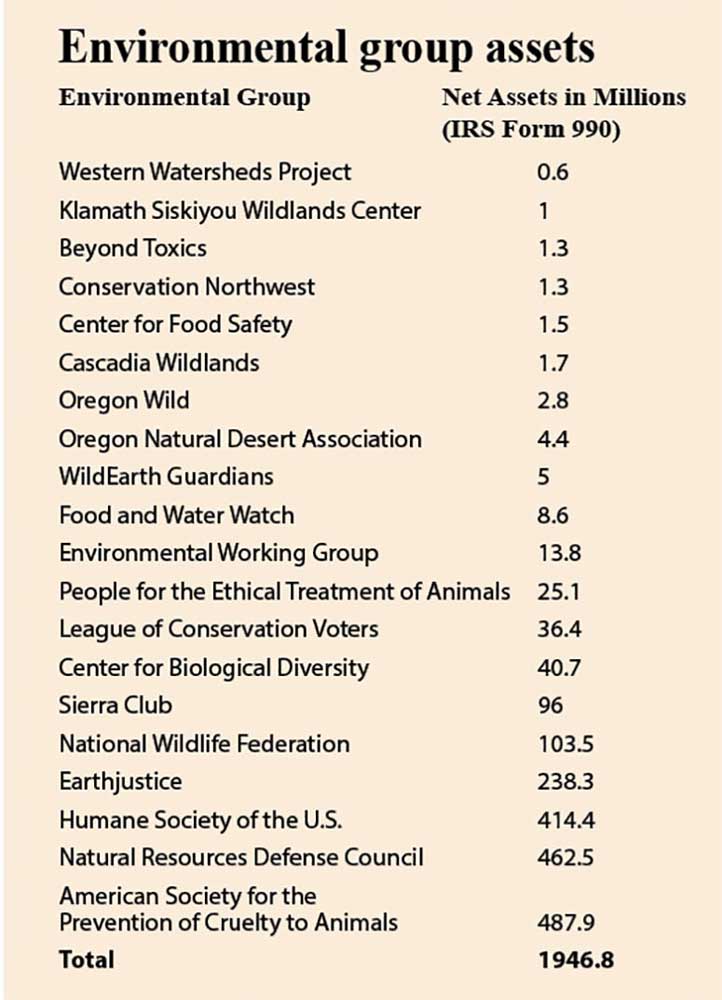

Though environmental advocates claim they are waging a “David versus Goliath” battle to protect natural resources, many of them have accumulated assets in the millions of dollars.

In some cases, their assets total in the hundreds of millions.

A Capital Press review of Internal Revenue Service filings by 20 nonprofit environmental organizations active in the West found they have total net assets of nearly $2 billion.

The net assets listed in the most recent tax filings available range as high as $414 million for the Humane Society of the United States, $462 million for the Natural Resources Defense Council and $487 million for American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Often a significant amount of the money is set aside as an endowment to generate income that can be spent in addition to donations from other sources.

“People are often surprised by the size of their war chests,” said a senior aide for the U.S. House Natural Resources Committee, which is investigating environmental group funding.

Because environmental organizations tend to consider their motives as beyond reproach, they’re often reluctant to have a spotlight shone on their finances, said the aide, who asked not to be linked to the committee’s investigation.

“We’re trying to bring this story to light. You have to point out where these things become a problem,” the aide said. “It’s difficult to find criticism of many of these groups.”

Major environmental groups and charitable foundations who’ve been targeted by Republican congressional investigations refused to comment on the claims or issued statements denying them.

One consultant whose business is connecting charitable foundations with environmental nonprofits said they’re subject to strict government oversight to maintain their tax-exempt status as nonprofits.

“People tend to forget there are sideboards and laws out there for a reason,” said the consultant, who asked not to be identified.

To have an impact on national and global policies, environmental groups must have the wherewithal to hire skilled legal and scientific professionals, since they’re often in conflict with powerful corporations or the U.S. government, which have vast resources, the consultant said.

“They do get amazing people, but they do need to be competitive,” the consultant said.

However, the funding network that’s allowed some environmental groups to achieve financial might has not gone unnoticed by critics on both the left and the right of the political spectrum.

For example, environmental nonprofits such as the Sierra Club, Natural Resources Defense Council and League of Conservation Voters have come under fire from conservative lawmakers, who believe at least some of their cash may derive from shadowy foreign sources that want to undermine the U.S. economy.

On the other hand, some critics claim that charitable foundations and other donors are in the dark about how the nonprofits spend their money.

“It’s hard for an outsider to understand what is going on behind the scenes. These things aren’t disclosed,” said Travis Joseph, president of the American Forest Resource Council, which represents the timber industry.

The fundraising prowess of the largest environmental nonprofits has also drawn attacks from progressive reformers, who claim a few groups dominated by white men are hoarding money to the detriment of smaller organizations — particularly those representing the interests of people of color.

Financial success tends to beget more success, according to an analysis of 30,000 environmental and public health grants from 220 foundations conducted by Yale University researchers.

“Foundations prefer to direct funding to organizations with significant revenues,” the study found. “Consequently, more than half of the grant dollars go to organizations with revenues of $20 million or more. Organizations with revenues under $1 million receive less than 4% of the grant dollars.”

Environmental groups trace their roots back more than a century to the movement to preserve American wilderness and protect it from logging, mining and development, which resulted in the creation of national parks and forests.

Their modern incarnation was shaped by federal laws passed in the 1960s and ’70s, such as the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act and Endangered Species Act, under which environmental nonprofits effectively became third-party enforcers.

Environmental groups began filing lawsuits alleging violations of these statutes, bringing them into conflict with the U.S. government and federally regulated industries, including agriculture and forestry.

To level the playing field between the nonprofit plaintiffs and the U.S. government 40 years ago, Congress passed the Equal Access to Justice Act, or EAJA, under which environmental groups can be compensated for court victories.

While nonprofits can recoup their litigation expenses from federal agencies if they prevail, they also raise money through donations and grants from individuals and charitable foundations.

Despite complaints about EAJA, the reality is that obtaining payouts from the federal government is usually a drawn-out ordeal, said Nick Cady, legal director for the Cascadia Wildlands nonprofit.

“Cascadia Wildlands doesn’t budget for EAJA fees unless they’re in hand already because it’s so small and unpredictable,” Cady said. “It’s a five-year delay in your paycheck. It’s not a way to make a living.”

Though lawsuits don’t generate most of the revenues for environmental groups, critics question whether nonprofit organizations with healthy balance sheets should receive money from the government if they are successful in court.

Individuals with a net worth over $2 million and companies with more than $7 million aren’t eligible to recover EAJA fees, but tax-exempt nonprofits aren’t subject to limits.

EAJA was intended to give the “small guy” a fighting chance against the U.S. Department of Justice, which is effectively “the nation’s largest law firm,” but it now often helps support environmental nonprofits with tremendous assets, said Karen Budd-Falen, an attorney and former Interior Department official who’s critical of the law.

“We’ve gone so far over the edge on that, the law is being abused,” she said.

As a first step, the federal government should at least track how much it’s paying out to environmental nonprofits and others and make that information available through a searchable database, Budd-Falen said.

“If it’s the public’s money, then I think the public ought to know,” she said. “If the public knew how much money we were paying to these groups, it would put pressure on Congress to fix the problem.”

Court-awarded attorney fees provide an incentive for environmental groups to file a large volume of lawsuits against the federal government rather than engage in meaningful restoration work, said Budd-Falen.

“Most of these groups don’t do a single thing on the ground to help anything, they just litigate,” she said.

That accusation is unfair and mischaracterizes the activities of groups like Cascadia Wildlands, which devote significant time and money to “field checking” the impacts of forest projects and other federal plans, said Cady, the organization’s legal director.

Such projects often occur in isolated areas that federal agencies don’t have the resources to thoroughly evaluate, so Cascadia Wildlands provides a more accurate picture of baseline conditions, such as the age of trees prior to harvest, he said.

“This has frequently headed off litigation before it started,” Cady said. “It’s not just to tee-up litigation or legal efforts.”

Overall, lawsuits pack more punch per dollar spent, as they can reverse harmful policies that affect vast swaths of public land, said Erik Molvar, executive director of the Western Watersheds Project nonprofit in Idaho.

By comparison, the same amount of money might restore only a few acres or stream miles with on-the-ground work, Molvar said. “It’s not very cost-effective in terms of the benefit you get versus the dollars you spend.”

Regardless of the potential to win litigation fees, environmental groups face an uphill battle in prevailing in court against the federal government, Cady said.

Scientifically and legally, the burden is on environmental plaintiffs to prove malfeasance by federal agencies, which are presumed to be the experts, he said.

“The government gets the benefit of every doubt,” Cady said. “It’s hard for us to win these suits. We have to prove there is something flagrantly illegal happening.”

Many courtroom battles pertain to remote forests and rangelands, but the effects of pollution on racial minorities, often due to industrial contamination in urban areas, have also long animated the environmental movement.

However, organizations focused on “environmental justice,” which advocate civil rights as well as air, water and soil protections, haven’t amassed nearly as much money as the most prominent national nonprofits, according to researchers from Yale’s School of the Environment.

“White-led organizations obtained more than 80% of the grants and grant dollars. Hence, white-male-led organizations received the most grants and grant dollars,” their study found. “Though 56% of the foundations funded organizations primarily focusing on people of color, less than 10% of the grants and grant dollars go to such organizations.”

Environmental justice groups tend to be “newer, smaller and more radical,” which partly explains the “tepid support,” the study found.

Beyond such considerations, charitable foundations have policies that give big environmental groups a fundraising advantage, the researchers said.

For instance, foundations are reluctant to disburse grants that would exceed a set percentage of an organization’s normal income stream, the study said.

“This means that organizations with revenues in the millions can apply for large grants,” the study said. “However, small organizations have to make do with small grants.”

Criticisms that environmental groups are “super white” are probably accurate, which is a reflection of the “white male leadership” across many corporate structures, said Cady of Cascadia Wildlands.

Awareness of the problem is leading environmental groups to remedy the imbalance by hiring more women and people of color for leadership positions, he said.

“I do think people are trying to incorporate diverse perspectives and interests,” Cady said.

Despite efforts to diversify their workforce, environmental groups can run into recruitment obstacles due to the sparsely inhabited landscapes on which they focus, said Molvar of the Western Watersheds Project.

“We work in remote rural areas often characterized by racism and perceived danger,” he said. “That might be a reason it’s harder for us to recruit people from diverse backgrounds. They might not feel safe out there.”

Regarding the preference that charitable organizations may have for large nonprofits, Molvar said he doesn’t consider it a major hindrance for the Western Watersheds Project, which is among the smaller nonprofits.

“It’s certainly a point of pride that we punch above our weight,” Molvar said.

Depending on donations from large foundations can be a disadvantage, as such donors can be “quite intrusive” in trying to set the agenda, he said.

“When you’re funded mostly by individuals, you don’t have that issue,” Molvar said.

The influence of large foundations is generally more passive than active, he said. In other words, they don’t directly throw their weight around, but only dispense money to certain types of projects.

“You need to change your mission and your goals to fit into what they want to fund, if that’s what you want to chase,” Molvar said. “If your work doesn’t fit in their categories, you don’t get the grant.”

Cascadia Wildlands is likewise among the smaller environmental nonprofits, which Cady said results from its concentration on local forest issues near Eugene, Ore.

Large foundations tend to fund organizations with a broader scope, while local residents are more interested in regional controversies, he said.

“They wouldn’t give money to the (Natural Resources Defense Council) to work on those issues, because they don’t,” Cady said, referring to one of the largest environmental nonprofits. “They’re working on bigger national policy agendas.”

Climate change, for example, has become a foremost concern for the environmental movement, involving litigation and policy discussions at the federal level.

Major nonprofits have devoted their resources to reducing carbon emissions — often pitting them against the domestic extraction of oil and gas.

Critics claim these policies align with those of hostile foreign nations whose economic interests are threatened by expanded American fossil fuel production.

Some conservative members of Congress have gone so far as to question whether Russia has funneled cash to environmental groups, relying on opaque fundraising processes to hide its tracks.

Investigations by the House Natural Resources Committee have raised such concerns, though it doesn’t allege every environmental group is a “pawn of a foreign government,” said the senior aide working for the committee.

In some cases, environmental groups may know that foreign actors are channeling money through foundations to affect U.S. energy policy, but in others, their interests may align unwittingly, the aide said.

Either way, the worry is that policies that suppress domestic oil and gas production help Russia and other foreign producers more than they curb global carbon emissions, the aide said.

“We have to make people aware of what that means. We’re going to be ceding that position to China or Russia,” the aide said. “We do it cleaner than anyone in the world.”

Among the groups who’ve faced such accusations, the Sierra Club declined to answer questions and a spokesperson for the League of Conservation Voters said the allegations have been “debunked several times over the years.”

The Natural Resources Defense Council issued a statement saying the nonprofit receives “no funding from the government of Russia” and doesn’t do “the bidding of any government — foreign or otherwise.”

Environmental groups involved in Western debates over logging and grazing on federal lands haven’t encountered similar allegations of foreign influence, but industry critics say their policies are still damaging to the region’s economy and people.

“They’re trying to litigate these agencies into submission,” said Andy Geissler, federal timber program director for the American Forest Resource Council. “If you delay a project long enough, there’s a good chance it will burn.”

In some cases, charitable foundations may not realize their money is being funneled to anti-logging activists and could be put to better use than litigation and lobbying, said Joseph, AFRC’s president.

“I think there’s a total disconnect there,” Joseph said. “They believe they’re funding collaboration. They believe they’re funding the middle ground. They’re clearly not.”

The consultant who advises foundations on environmental grants said their eyes are open to how their money’s being used, though their political and financial motivations are difficult to generalize.

“There is no one donor. It is complicated,” the consultant said. “Some care about the tax deduction, others don’t.”

Likewise, nonprofits all have their own strategies for fundraising and how much they solicit from charitable foundations, private donors, community partners and government agencies, the consultant said.

“If you’ve met one environmental organization, you’ve met one environmental organization,” the consultant said. “Each one is set up differently.”