ONLINE Dan Fulleton Farm Equipment Retirement Auction

THIS WILL BE AN ONLINE AUCTION Visit bakerauction.com for full sale list and information Auction Soft Close: Mon., March 3rd, 2025 @ 12:00pm MT Location: 3550 Fulleton Rd. Vale, OR […]

Published 9:00 am Thursday, April 30, 2020

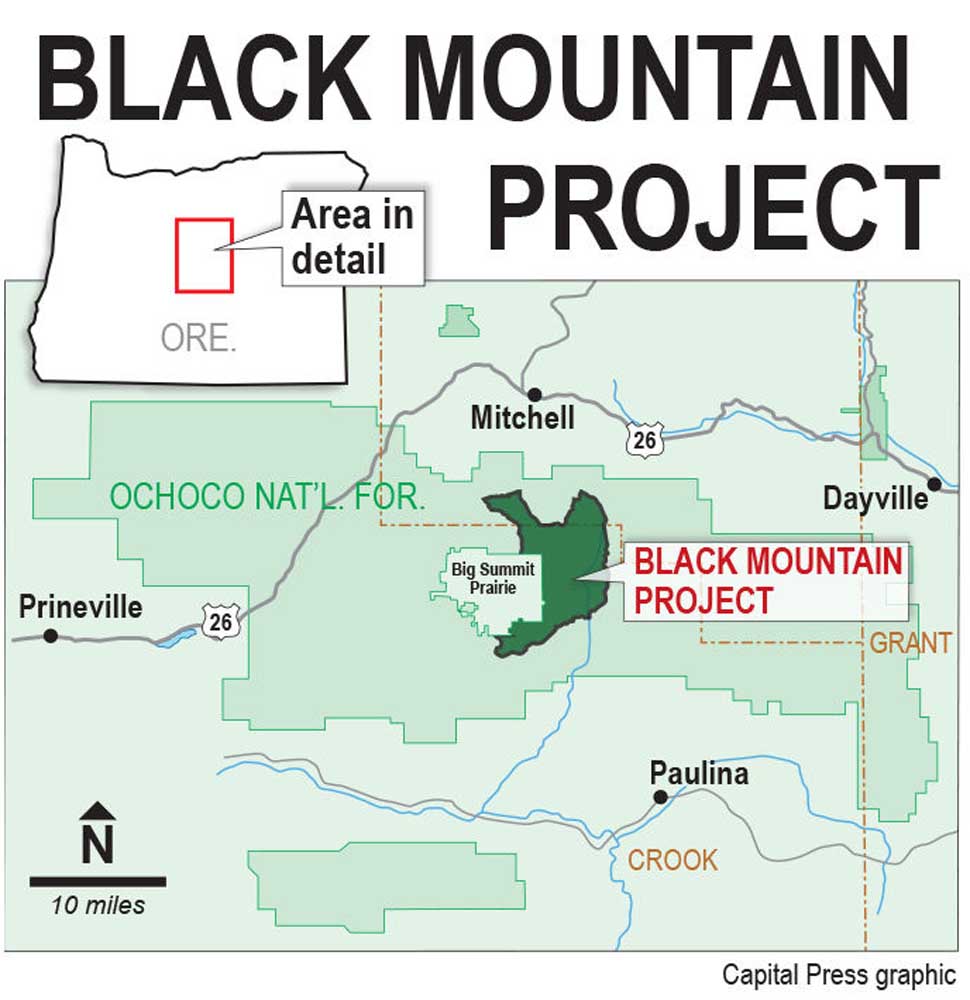

A 15,700-acre thinning and vegetation management project in Oregon’s Ochoco National Forest has come under legal fire from allegedly failing to protect elk and riparian habitats.

The Central Oregon Landwatch and Oregon Wild nonprofits have filed a complaint seeking to block the project, which is intended to improve fire and disease resistance, until the U.S. Forest Service ensures it complies with environmental laws.

However, the plaintiffs object to specific treatments affecting elk and water quality, not to the thinning of most upland areas, said Rory Isbell, attorney for Central Oregon Landwatch. “We’re not challenging the majority of project activities.”

The Forest Service approved the project in late 2019 and management activities are expected to begin in June. About 46% of the project’s entire 34,000-acre footprint will be treated, including about 5,000 acres of commercial thinning. Logging will generate about $1.5 million in revenue, enough to offset 40% of the $3.7 million cost of restoration activities.

A representative of the Ochoco National Forest said the Forest Service doesn’t comment on pending litigation.

While planning the project, the Forest Service didn’t identify areas that Rocky Mountain elk use for breeding and calving, which are often near streams, according to the complaint.

The agency will instead survey for calving sites two weeks before work begins in an area to be treated, then postpone the activity if any are found. The “wallows” used for breeding purposes will also be surveyed and flagged prior to forest work.

The plaintiffs believe the Forest Service must instead locate breeding and calving sites while they’re being used by elk but long before logging occurs, said Oliver Stiefel, attorney for the plaintiffs with the Crag Law Center.

Elk display “site fidelity” — returning to the same areas year after year — so this would be more accurate than surveying for breeding and calving sites before the relevant behaviors occur, he said.

“The likelihood of being able to locate any calving elk is slim to none,” Stiefel said. “If you’re doing these surveys well before they get there, you’re obviously not going to find anything.”

More than 200 miles of “roadwork activities” are also authorized by the project, including nearly 23 miles of new road building and nearly 24 miles of road re-construction, which the plaintiffs argue will fragment undisturbed elk habitat.

Although the Forest Service identifies some roads as “temporary,” the timber sale will occur over 10 years, so the disturbance from a road during that time is significant for an elk’s life cycle, said Stiefel.

“Temporary is a bit of a misnomer,” he said.

Many roads that are “administratively closed” within the national forest are still widely used, so the plaintiffs would prefer that the Forest Service calculate the density of functionally open roads to see how they’re affecting elk, Stiefel said.

Nearly 500 acres within the project will be commercially thinned within riparian habitat conservation areas, but the plaintiffs claim the Forest Service should establish 300-foot buffers around streams rather than the 70-foot setbacks it plans to use.

“The project doesn’t require adequate buffers along riparian areas where we don’t believe logging should occur,” said Isbell.

Timber harvested from the project will likely go to mills within about 200 miles of its boundaries, which is basically “anything in Eastern Oregon, anything east of the Cascades,” said Lawson Fite, attorney for the American Forest Resource Council, which represents timber interests.

“That’s where things have gotten with the difficulty of sourcing timber,” Fite said.

The project was reviewed by a collaborative group of outside stakeholders and appears to have a lot of local support, as it will help the local economy as well as wildlife, he said.

“I didn’t see any glaring deficiencies,” Fite said of the project’s legal defensibility. “This doesn’t seem like one that should be the target of a lawsuit.”

The scale of the project may have contributed to it being challenged by environmental groups, he said. “It’s a double-edged sword, where you try to get a lot of work done, but it can be kind of a target.”